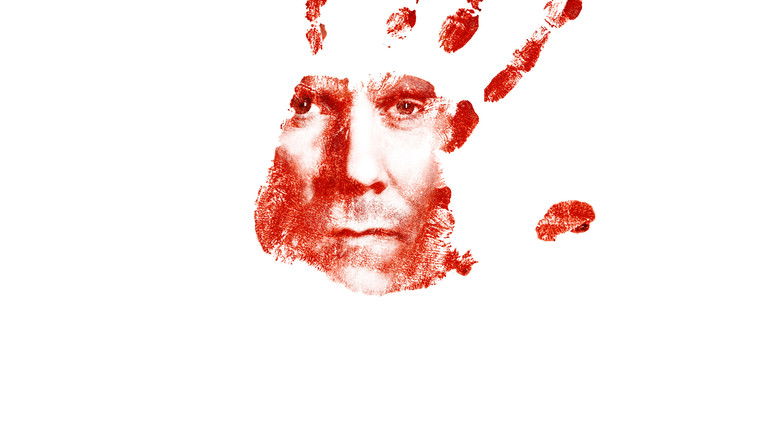

The Cult of the MacabreWhen we discuss the "Golden Age of Television," we often point to the slow-burn character studies of *Mad Men* or the moral decay of *Breaking Bad*. But in 2013, Kevin Williamson (the architect of 90s meta-horror like *Scream*) attempted something more visceral on network television: he tried to weaponize the slasher genre for a weekly audience. *The Following* is not merely a police procedural; it is a brutal, frantic meditation on the seductive power of violence. While it occasionally buckles under the weight of its own nihilism, it offers a fascinating, if imperfect, look at the symbiosis between the hunter and the hunted.

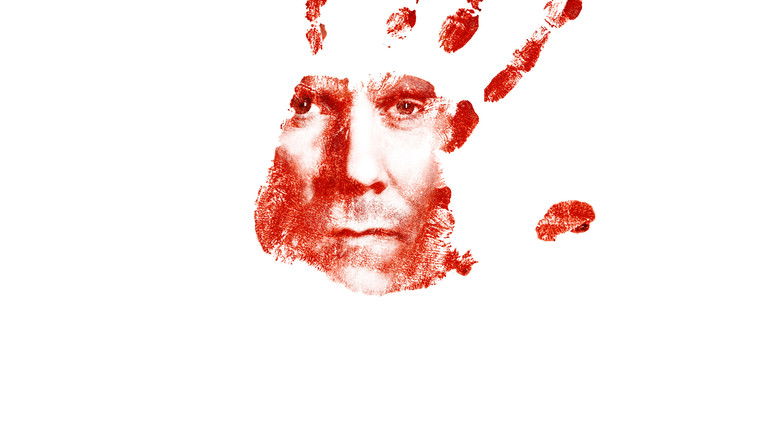

Visually, *The Following* eschews the warm, glossy filters typical of network dramas for a palette of steel grays, bruises, and arterial reds. The atmosphere is suffocating, often reflecting the internal state of its protagonist, Ryan Hardy (Kevin Bacon). Hardy is not the shiny, capable hero of *CSI*. He is a wreck—a walking scar tissue of alcoholism and heart failure, living in a world where every shadow could conceal a knife. The camera work emphasizes this paranoia, often lingering on open doors or empty hallways just long enough to make the viewer uncomfortable. The violence is sharp and often performative, a choice that mirrors the antagonist’s obsession with the theatricality of death.

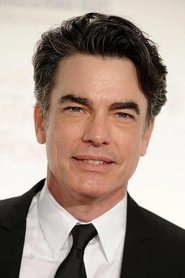

At the narrative's center is a grotesque romance of wits between Hardy and Joe Carroll (James Purefoy). Purefoy plays Carroll not as a foaming madman, but as a failed novelist turned charismatic professor who treats murder as a form of high art. He wraps his atrocities in the velvet cloak of Romantic literature, specifically the works of Edgar Allan Poe. This is where the series finds its most compelling, if occasionally pretentious, hook: the idea that evil can be intellectualized and taught. Purefoy and Bacon share an electric chemistry—Hardy the blunt instrument of justice, Carroll the conductor of a symphony of screams. They are two sides of the same obsessed coin, neither able to exist without the other’s validation.

However, the show’s most terrifying concept is not the central villain, but the "Followers" themselves. Williamson taps into a primal fear of the unknowable neighbor. The cult members are not visibly monstrous; they are nannies, police officers, and shopkeepers. In the age of social media and radicalization, the idea of a charismatic leader activating "sleeper agents" feels disturbingly prescient. The terror comes from the loss of safe spaces; when the seemingly innocent girl next door pulls out an ice pick because a literature professor told her to, the social contract dissolves.

Ultimately, *The Following* is a flawed masterpiece of pulp tension. It requires a suspension of disbelief that can be demanding—the FBI’s incompetence often serves the plot rather than logic—but it succeeds as a mood piece. It asks us to stare into the abyss and acknowledges, with a wink, that we are watching because part of us enjoys the darkness. It remains a sharp, adrenaline-fueled bridge between the standard procedural and the prestige horror that would follow in its wake.