The Baroque Ballet of the BoogeymanIf cinema is a language, action is often treated as its guttural scream—loud, chaotic, and lacking the grammar of "serious" drama. But in *John Wick: Chapter 3 - Parabellum*, director Chad Stahelski proves that violence can be spoken in iambic pentameter. This is not merely a sequel; it is a hyper-stylized descent into a neon-soaked underworld that feels less like a crime thriller and more like a violent fever dream of Buster Keaton. Where modern blockbusters often obscure their action with rapid-fire editing to hide the seams, *Parabellum* widens the lens, inviting us to witness the exhaustion of its performer in a way that feels almost sacred.

From the opening minutes, Stahelski establishes a visual dialect that is uniquely his own. The film picks up mere seconds after the previous chapter, with John Wick (Keanu Reeves) excommunicated and running out of time. The aesthetic is oppressive yet beautiful—a "high-tech baroque" where the streets of New York are slick with rain and bathed in the harsh blues and purples of a world that has rejected him. The lighting does more than set the mood; it narrates the hierarchy. The cool, detached blues of the High Table contrast sharply with the warmer, golden hues of the sanctuaries Wick seeks but can no longer inhabit. This isn't just style for style's sake; it is world-building through color, creating a mythological space that feels ancient despite the modern weaponry.

The film's brilliance lies in its transparency. In an era of CGI armies, Stahelski—a former stuntman himself—insists on the tangible reality of the human body. We see this most clearly in the early confrontation within an antique shop. The scene is a masterclass in physical comedy and brutality, reminiscent of silent era slapstick. When Wick and his assailants realize they are standing in a hallway of knives, the pause is almost theatrical before the chaos ensues. Shattering glass becomes a recurring motif, stripping away cover and leaving the characters exposed. The camera doesn't flinch or cut away; it holds the gaze, forcing the audience to appreciate the sheer athletic endurance required to survive this universe.

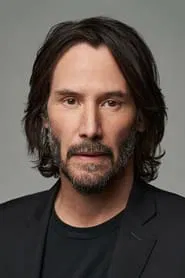

At the center of this storm is Reeves, whose performance is a study in physical melancholy. He moves with a weary precision that suggests a man burdened not just by his enemies, but by his own legend. There is a profound sadness in Wick—a desire for peace that is constantly interrupted by the necessity of war. He is a reluctant Sisyphus, pushing the boulder of his own survival up a mountain of bodies. The film strips him of his suits, his allies, and his weapons, reducing him to his primal core, yet he remains driven by a singular, heartbreaking motivation: the memory of a love that the world is trying to make him forget.

Ultimately, *Parabellum* challenges the viewer to reconsider the value of action cinema. It asserts that movement is character, and that a well-choreographed fight scene can possess the same emotional weight as a soliloquy. The narrative may be thin, serving mostly as a skeleton to support the muscle of the set pieces, but to criticize it for that is to miss the point. This is pure cinema—kinetic, visual, and unrepentant. It elevates the "shoot-em-up" genre into a form of abstract art, leaving us breathless not just from the adrenaline, but from the sheer audacity of its execution.