The Deafening Silence of a Stolen LandThe opening shot of Warwick Thornton’s *Sweet Country* is a masterclass in visual metaphor: a close-up of a billy can over a roaring fire, water violently boiling as tea and sugar are tossed in, churning into a dark, frothing mixture. It is an elemental alchemy that mirrors the film’s setting—1920s Central Australia—where the collision of colonial entitlement and Indigenous endurance is about to spill over. Thornton, an Indigenous auteur of profound sensitivity, has not merely made a Western; he has dismantled the genre’s machinery and reassembled it to tell a story of tragic inevitability.

Thornton, serving as both director and cinematographer, rejects the romanticized sweep of the classic Hollywood frontier. There are no heroic crane shots here, no sweeping orchestral swells to manipulate the audience's emotions. Instead, the film is aggressively silent. The soundscape is composed entirely of the wind hissing through the scrub, the crunch of boots on salt flats, and the buzzing of flies. This sensory deprivation forces the viewer to lean in, to inhabit the sweltering tension of the Northern Territory. The camera stays low, grounded at eye level, refusing to grant the audience a "god’s eye view" of a land where God seems largely absent, despite the Bible verses quoted by the characters.

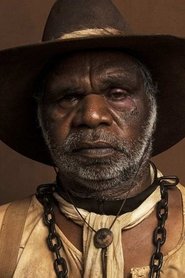

The narrative hangs on a singular, fatal moment. Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris), an Aboriginal stockman, kills a white station owner, Harry March (Ewen Leslie), in self-defense. In any other jurisdiction, or perhaps in a different skin, this would be a clear-cut case. But in the fragile hierarchy of the outback, a black man killing a white man is an overturning of the natural order. Sam knows this. He does not wait for the police; he takes his wife and flees into the "sweet country"—the harsh, beautiful, indifference of the desert that he knows better than his pursuers.

Thornton refuses to paint his white characters with a single brush, though he spares them no judgment. We have the toxic, shell-shocked alcoholism of March, a man whose soul was likely left in the trenches of WWI; the pragmatic, brutish lawman Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown); and the moral compass, Fred Smith (Sam Neill), a preacher who believes "we are all equal in the eyes of the Lord." Yet, even Smith’s kindness is impotent against the structural rot of the society he inhabits. He is a good man in a bad system, and the film quietly questions whether his goodness actually saves anyone.

The emotional anchor of the film is Hamilton Morris as Sam Kelly. A non-actor, Morris delivers a performance of monumental stillness. He speaks very little, but his face carries the weight of a history written in blood and displacement. When he is eventually put on trial—in an absurd, makeshift court set up on the dust—his silence is louder than the legal arguments swirling around him. He is a man who understands that the "law" is a foreign language spoken by invaders, having little to do with true justice.

By the time the credits roll, Thornton leaves us not with resolution, but with a haunting interrogative. "What chance has this country got?" Sam Neill’s character asks, staring into a void that feels uncomfortably close to our present. *Sweet Country* suggests that until the silence of that history is broken and the boiling pot is addressed, the chance remains slim. It is a film of rugged beauty and devastating sorrow, a necessary correction to the myths we tell ourselves about the frontier.