The Ghost in the MachineHorror, at its most potent, is rarely about the monster itself. It is about what the monster represents—the return of the repressed, the manifestation of grief, or the encroaching rot of a specific social anxiety. In Emma Tammi’s *Five Nights at Freddy’s*, a film weighted by the colossal expectations of a digital generation, the monsters are literal hulking masses of metal and fur. Yet, Tammi attempts to weave a narrative not just about jump scares, but about the paralyzing inertia of past trauma. While the film occasionally buckles under the heaviness of its own lore, it succeeds as a surprisingly melancholy mood piece about a young man haunted by an empty chair at the dinner table.

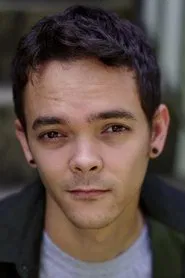

Visually, Tammi and cinematographer Lyn Moncrief have crafted a world that feels stuck out of time. The film’s aesthetic is not merely 1980s nostalgia; it is a deliberate stagnation. The pizzeria itself is a tomb, preserved in the dust and neon of a bygone era. Tammi uses the claustrophobic framing of the security office to mirror the protagonist Mike’s (Josh Hutcherson) internal state. He is a man who sleeps not to rest, but to work—using his dreams to litigate a cold case from his childhood. The lighting is often oppressive, utilizing the sickly greens and electric blues of the monitors to illuminate faces, suggesting that these characters are already ghosts, illuminated only by the artificial glow of the past.

The crowning achievement of the film’s visual language, however, lies in the animatronics themselves. Created by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, Freddy, Bonnie, Chica, and Foxy are not sleek CGI creations but tactile, lumbering realities. They possess a terrifying weight. When they move, you can almost hear the servos whining and the gears grinding. Tammi wisely shoots them with a mixture of awe and dread, allowing their sheer physical presence to dominate the frame. They are uncanny effigies of childhood joy currdled into something malignant, serving as the perfect objective correlative for Mike’s ruined innocence.

At its heart, this is a story about the devastating cost of guardianship. Hutcherson delivers a performance of weary, twitchy exhaustion that grounds the more supernatural elements. His Mike is not a hero; he is a casualty of a broken family system, fighting a custody battle that feels just as threatening as the killer robots. The film posits that the true horror isn't getting stuffed into a suit, but failing those who depend on you. The dream sequences, repetitious and frustrating, emphasize Mike’s inability to move forward. He is stuck in a loop, much like the animatronics programmed to perform the same songs forever. When his younger sister Abby (Piper Rubio) begins to bond with the machines, the film touches on a profound sadness: the way neglected children will seek connection in the most dangerous of places, mistaking a mechanical grip for a holding hand.

Ultimately, *Five Nights at Freddy’s* occupies a strange, liminal space in modern horror. It rejects the hard-R gore that genre purists crave, opting instead for an atmosphere of "cozy dread" that feels accessible yet disturbing. It is a gateway horror film, yes, but one that respects the emotional intelligence of its audience. It suggests that while we cannot change the tragedies of our origins, we must eventually wake up from the dream and face the monsters in the waking world. It is an imperfect, uneven machine, but one with a surprisingly beating heart beneath its steel ribcage.