The Mechanics of MiracleThere is a pervasive cynicism in modern holiday cinema, a genre often relegated to the assembly line of streaming services where treacle and formula are weighed by the pound. We expect the red suit, the magic dust, and the instant moral redemption. But *Klaus* (2019), the directorial debut of *Despicable Me* creator Sergio Pablos, is a startling rejection of that plastic sentimentality. It does not begin with magic; it begins with bureaucracy. By framing the genesis of Santa Claus through the eyes of a selfish, materialistic postman in a frozen, hateful purgatory, Pablos achieves something rare: he deconstructs a myth to find its human pulse.

The immediate marvel of *Klaus* is its visual language, which feels less like a movie and more like a living storybook illustration that has refused to be flattened. In an era where hyper-realistic 3D CGI suffocates the imagination, Pablos and his team at SPA Studios deployed a revolutionary technique—volumetric lighting applied to hand-drawn 2D animation. The result is a texture that feels tactile, almost grainy, with light that physically carves characters out of the shadows.

Smeerensburg, the film’s setting, is a masterclass in production design—a gray, jagged nightmare of angular architecture and monochromatic misery. The town is physically shaped by the hatred of its inhabitants, the Krums and the Ellingboes. This visual hostility makes the eventual introduction of warmth—the golden glow of a lantern, the crimson of a handmade toy—feel earned rather than decorative. The animation doesn't just show us the cold; it makes us shiver, so that the eventual thaw feels like a spiritual relief.

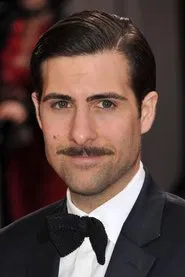

At the narrative’s center is Jesper (Jason Schwartzman), a pampered scion of the postal academy who is exiled to this frozen rock to prove his worth. His initial motivation is purely transactional: he needs children to send letters so he can meet his quota and escape. This cynicism is the film’s secret weapon. By grounding the "magic" of Santa Claus in accidental misunderstandings and selfish schemes, the script creates a grounded logic for the impossible. The flying reindeer, the chimney descent, the naughty list—each piece of the Santa lore is explained away as a series of chaotic coincidences interpreted by wide-eyed children.

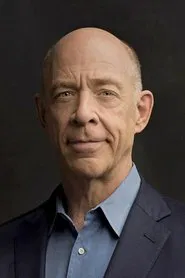

However, the emotional anchor is Klaus himself (J.K. Simmons). Simmons plays the woodsman not as a jolly saint, but as a man paralyzed by grief, a widower whose workshop is a mausoleum of unfulfilled dreams. The relationship between Jesper and Klaus is not a sudden friendship but a slow negotiation of broken people finding utility in one another. When the transformation comes, it isn't because of elves or magic spells; it is because, as the film’s central mantra suggests, "A true selfless act always sparks another." The film argues that goodness is a contagion, a social mechanic as powerful as the generational feuds that poisoned the town.

*Klaus* stands as a defiant correction to the idea that traditional animation is a relic. It proves that the medium is capable of profound depth and lighting that rivals any Pixar production, while retaining the expressive, imperfect soul of the artist's hand. It is a film that acknowledges the darkness of human nature—our capacity for petty hatred and generational grudges—only to show how easily that darkness can be broken by a single, tangible act of giving. It is not just a great Christmas movie; it is a great film about the labor of empathy.