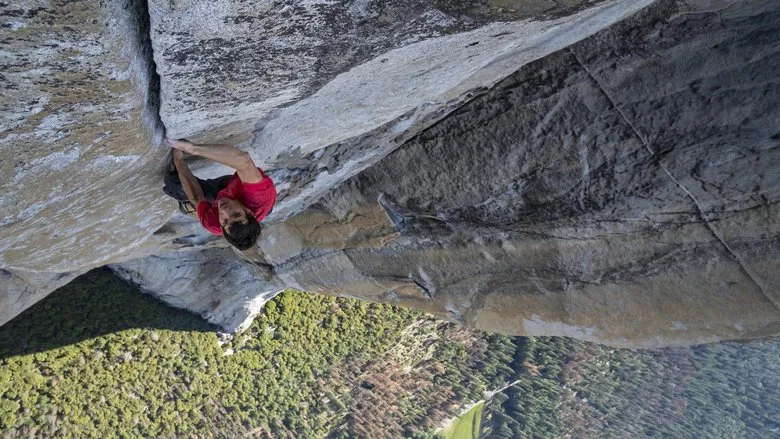

The Geometry of the AbyssTo categorize *Free Solo* merely as a sports documentary is a misunderstanding of its fundamental nature. While it ostensibly tracks an athletic feat—Alex Honnold’s quest to scale Yosemite’s El Capitan without ropes—it plays out as a psychological thriller, bordering on body horror. Directors Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi have not just filmed a climb; they have captured a profound existential dialogue between a man and the void. The result is a film that vibrates with a terrifying, quiet intensity, asking not just if a man can achieve perfection, but what he must sacrifice in his humanity to do so.

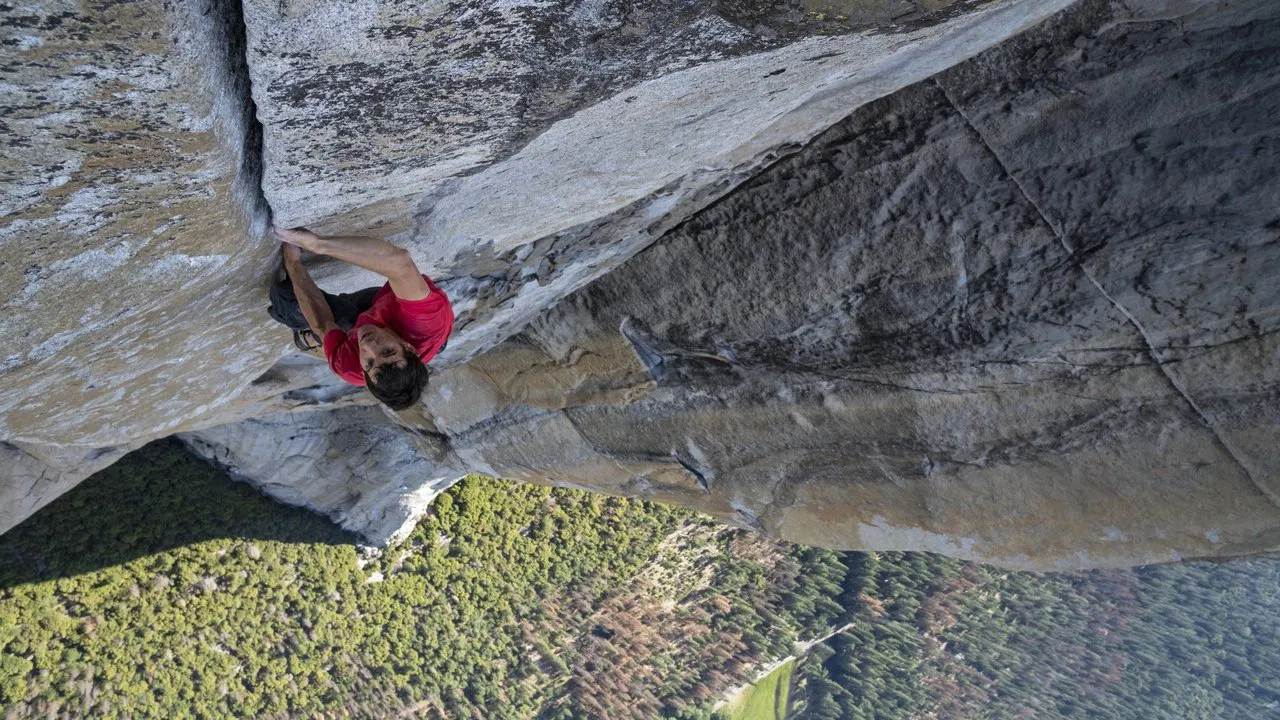

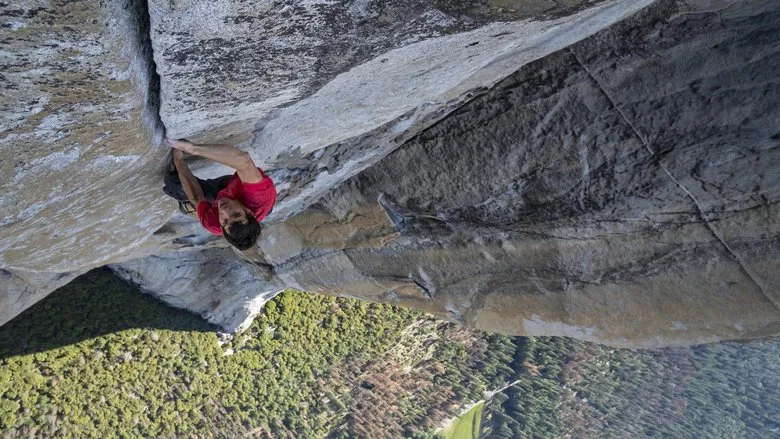

The visual language of *Free Solo* is defined by a suffocating sense of scale. Chin, an elite climber himself, understands that the terror of El Capitan lies not in the action, but in the stillness. The cinematography alternates between vertigo-inducing drone shots that reduce Honnold to a speck of red dust against a sea of granite, and microscopic close-ups of his fingertips pressing into razor-thin crimps. There is no shaking camera work here, no manufactured "Bourne identity" chaos. The camera is steady, almost surgical. This stability makes the danger palpable; we can clearly see that the only thing keeping Honnold from a three-thousand-foot plummet is the friction of rubber on rock and a terrifyingly calm state of mind.

The film’s central tension, however, is not the granite wall, but the ethical nightmare faced by the filmmakers. The "observer effect" hangs heavy over the production: does the presence of the camera make death more likely? Chin and his crew are not passive observers; they are friends of the subject, burdened with the heavy knowledge that they might be framing a shot of their friend’s death. This meta-narrative adds a layer of dread that permeates every frame, turning the camera lens into a loaded gun.

At the heart of this abyss is Honnold himself, a figure of fascinating, almost alien stoicism. The film wisely spends significant time on the ground, exploring the wiring of a brain that seems immune to normal fear responses. An MRI scene reveals his amygdala lies dormant where others’ would flare, a biological explanation for his ability to exist comfortably in the "death zone."

Yet, the emotional anchor of the film arrives in the form of Sanni McCandless, Honnold’s girlfriend. She represents the "real world"—messy, emotional, and attached to life—crashing against Honnold’s monastic singularity. The friction between them is palpable. For Honnold, intimacy is a distraction; for Sanni, his detachment is a puzzle to be solved. The film posits that to be the greatest free soloist in history, one may have to sever the very emotional tethers that make us human. His eventual success on the wall feels less like a triumph of spirit and more like a transcendence into a realm where human concerns no longer apply.

The climax, featuring the infamous "Boulder Problem"—a complex sequence requiring a karate-kick maneuver over open air—is a masterclass in editing. The silence is deafening. We are not watching an athlete; we are watching a performance artist executing a routine where the penalty for a missed cue is oblivion. *Free Solo* ultimately succeeds because it refuses to romanticize the danger. It presents the sublime and the grotesque in equal measure, leaving us in awe of the achievement but deeply unsettled by the price of admission. It is a portrait of obsession so pure it looks like madness.