✦ AI-generated review

The Rearview Mirror of Trauma

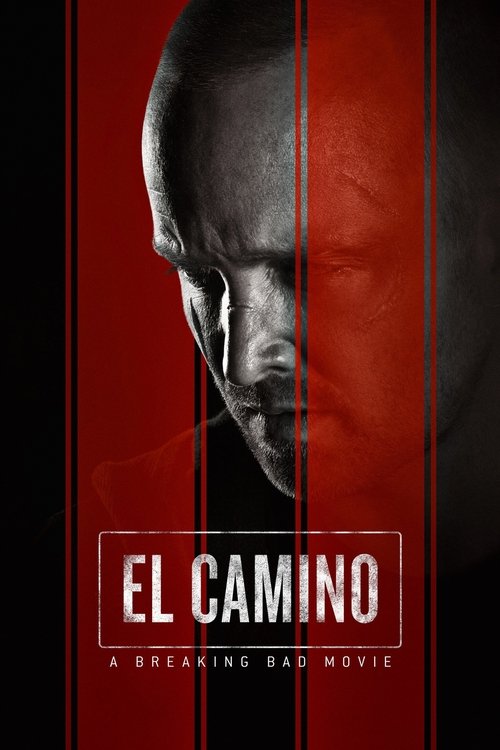

In the modern landscape of cinematic revivals, the "legacy sequel" usually arrives with the subtlety of a sledgehammer, desperate to justify its existence through bigger explosions and higher stakes. *El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie*, however, does something largely unprecedented: it dares to be quiet. Written and directed by Vince Gilligan, this film is not an attempt to outdo the operatic crescendo of its parent series, but rather a necessary exhale—a neo-Western study of what happens after the getaway car speeds off into the night. It is a film less about "breaking bad" and more about the agonizing, silent work of breaking free.

Gilligan’s visual language has always been rooted in the stark geometry of the American Southwest, but here, the cinematography serves a different master. Where the series was often about the grandeur of hubris—Walter White dominating the frame—*El Camino* is defined by the claustrophobia of trauma. The film exists in the tight spaces of Jesse Pinkman’s PTSD: the underside of a car, the interior of a refrigerator, the cage of his own memory. Even when Jesse (played with shattering vulnerability by Aaron Paul) is physically free, the camera traps him in frames within frames, emphasizing that liberation is not a physical act, but a psychological exorcism.

The film’s most chilling sequence—and its artistic centerpiece—is not a shootout, but a domestic afternoon with the sociopathic Todd Alquist (Jesse Plemons). In these flashbacks, Gilligan strips away the "cool" veneer of the criminal underworld to reveal the banality of evil in its purest form. Watching a broken Jesse forced to help dispose of a body simply because he is too conditioned to resist is a horror movie disguised as a crime drama. It recontextualizes Jesse not as a participant in the meth empire, but as its primary victim. The terror here isn't the threat of death; it's the total erasure of the self.

Aaron Paul’s performance anchors this narrative with a physicality that renders dialogue almost unnecessary. He wears the scars of his captivity like a second skin. In the series, Jesse was the loud, tragic moral center, often flailing against the current. In *El Camino*, he is a ghost haunting his own life. The "conversations" he has with the dead—flashbacks involving key figures from his past—are not mere nostalgic cameos for the audience’s benefit; they are the fragments of a man trying to remember who he was before he became a product. The reunion with Walter White, set in a brightly lit diner of the past, emphasizes the tragic gulf between Walt’s ego-driven ambition ("You didn’t have to wait your whole life to do something special") and Jesse’s desperate need for a simple, uncorrupted life.

Ultimately, *El Camino* rejects the nihilism that defined Walter White’s end. If the series was a study of transformation into a monster, this film is a study of the reclamation of humanity. It culminates in a western-style duel that feels earned not because of the violence, but because it is the first time Jesse pulls the trigger solely for his own salvation, not at the behest of a manipulator.

Is *El Camino* "essential" viewing in terms of plot mechanics? Perhaps not; the series finale left Jesse’s fate ambiguous enough to satisfy. But as a piece of emotional architecture, it is vital. It grants dignity to the survivor, allowing Jesse Pinkman to stop watching his life through the rearview mirror and finally look at the road ahead.