The Myth of Muscle and MelodyTo watch S.S. Rajamouli’s *RRR* is to remember that cinema was once a carnival art—a place where the laws of physics were merely suggestions and the human spirit was capable of feats that would shatter a lesser medium. In an era where Western blockbusters often feel apologetic about their own scale, hiding behind irony or "gritty realism," Rajamouli offers a corrective that is as subtle as a tiger leaping from a cage. He does not deconstruct the hero; he apotheosizes him. This is not a film that asks if we can believe a man can fly; it demands we ask why we ever settled for men who walk.

The film’s premise is a stroke of historical fan fiction, reimagining two real-life Indian revolutionaries, Komaram Bheem (N.T. Rama Rao Jr.) and Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan), not as dusty figures in a textbook, but as elemental forces. Rajamouli visually codes them as water and fire—Bheem the innocent, unstoppable protector of the forest, and Raju the searing, disciplined soldier of the empire (with a secret). Their meeting, a high-wire rescue of a child beneath a bridge, serves as a thesis statement for the director’s visual language. It is a ballet of suspension cables, flags, and clasping hands that rejects the "cut-to-black" editing of modern action for long, fluid takes that emphasize the geography of cooperation.

Crucially, the film’s spectacle is never empty; it is the externalization of internal emotion. When the characters defy gravity, it is because their emotions—grief, loyalty, rage—are too heavy for the ground to hold. The much-discussed "Naatu Naatu" sequence is the perfect encapsulation of this philosophy. In a lesser film, a dance-off against colonial snobs would be a moment of levity. Here, it is combat. The synchronization between Charan and Rama Rao Jr. is not just choreography; it is a display of a unified front, a physical manifestation of a friendship that is rapidly becoming the film’s true political ideology.

However, beneath the dopamine rush of motorcycles used as clubs and arrows that decapitate, there lies a more complex, perhaps troubling, conversation about myth-making. Rajamouli leans heavily into the iconography of the *Ramayana*, transforming his historical freedom fighters into literal avatars of Hindu deities by the third act. While this provides a rousing, near-religious catharsis, it also flattens the complex, secular history of Indian independence into a specific, monolithic shape. The British antagonists are cartoonishly evil—vampiric caricatures that exist solely to be smashed—which works within the film's operatic logic but strips the colonial critique of any nuance beyond visceral satisfaction.

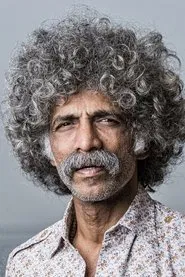

Yet, to critique *RRR* solely for its lack of nuance is to miss the point of its design. It operates on the level of fable, not history. The performances anchor this towering ambition. Ram Charan’s eyes hold a stoic, simmering pain that grounds the film's second half, while N.T. Rama Rao Jr. brings a soulful physicality that prevents Bheem from becoming just a blunt instrument of war. Their chemistry is the film's most potent special effect, selling the idea that male friendship can be a revolutionary act in itself.

Ultimately, *RRR* succeeds because it is entirely sincere in its excess. It is a film that wears its heart on its blood-soaked sleeve, inviting the audience to abandon cynicism and embrace the melodrama. In a global cinematic landscape often paralyzed by the need to be "smart" or "grounded," Rajamouli reminds us that sometimes, the most intelligent thing a filmmaker can do is treat the audience’s capacity for wonder with absolute seriousness. It is a roar that echoes long after the credits roll, a testament to the power of myth to move not just mountains, but the human pulse.