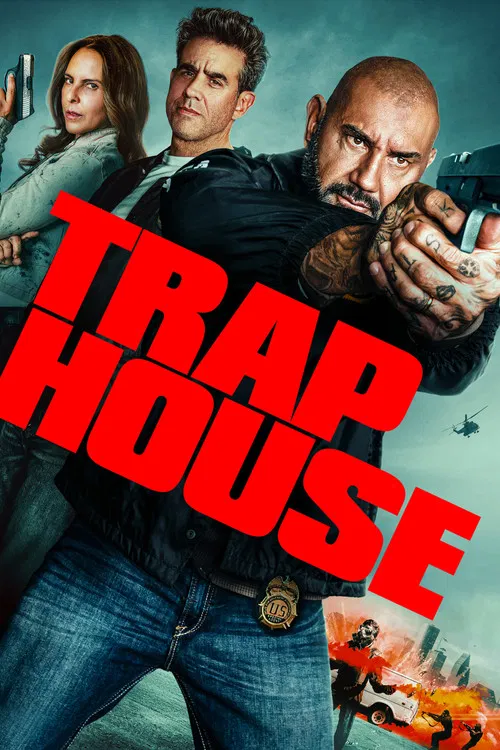

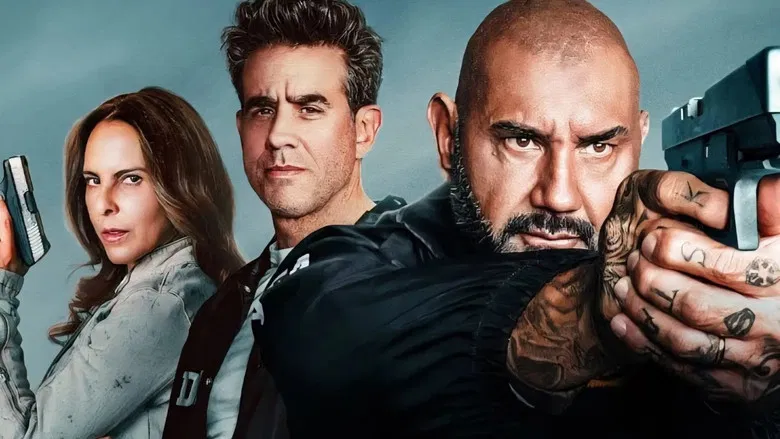

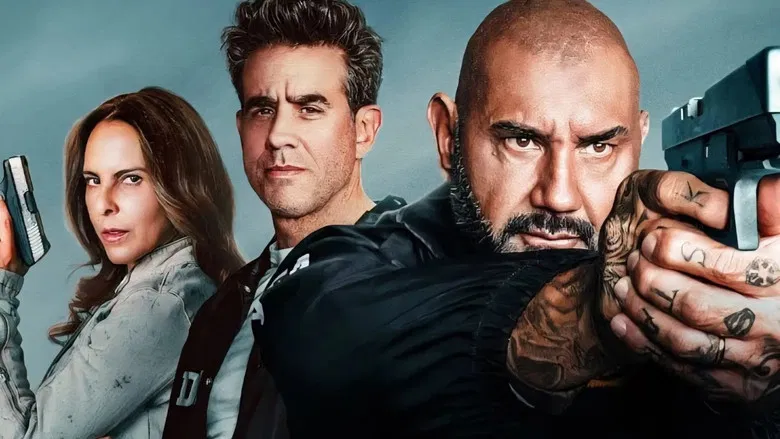

The Weight of SilenceThere is a moment early in Michael Dowse’s *Trap House* where the cacophony of gunfire fades, leaving only the hum of a desert wind and the heavy breathing of Ray Seale (Dave Bautista). In this quietude, Dowse suggests a film that is not merely about ballistics, but about the suffocating inheritance of violence. While the marketing sells a high-octane collision between *Sicario* and *The Goonies*—DEA agents hunting thieves who turn out to be their own teenage children—the film’s true ambition lies in deconstructing the walls we build to protect our families, and how those same walls often become prisons.

Dowse, a director who has previously danced on the edge of brutality and comedy with *Goon*, here attempts a tonal tightrope walk that is precarious, if not always graceful. Visually, *Trap House* is bathed in the harsh, unforgiving amber of the borderlands, a stark contrast to the sterile, blue-lit interiors of the tactical operation centers. This dichotomy is not accidental; it represents the two worlds the characters inhabit: the "clean" theoretical violence of the state and the messy, visceral reality of the street. The camera often lingers on Bautista’s face—a landscape of weathered regret—suggesting that the real trap house isn't the cartel stronghold, but the emotional isolation of a father who cannot speak to his son without an intermediary of silence.

The narrative hook is undeniably audacious: a group of teens, led by Ray’s son Cody (Jack Champion), utilizing their parents' own classified intel to rob the very cartels their fathers are hunting. It is a premise that teeters on the absurd, threatening to collapse under the weight of its own suspended disbelief. Yet, Dowse grounds this teenage rebellion in a grim socio-economic reality. The kids aren't stealing for thrills; they are stealing because the system that employs their parents has failed to protect the family of a fallen officer. It is a biting critique of institutional loyalty, suggesting that the "good guys" are often left behind by the very structures they serve.

However, the film’s emotional core struggles to breathe amidst the requisite set pieces. While the action is competent—chaotic, loud, and dusty—it occasionally drowns out the more interesting intergenerational drama at play. We see the teenagers mimicking the tactical precision of their parents, a chilling mirror image that asks whether violence is genetic or learned. But the script often retreats into genre conventions just when it verges on profound discovery, substituting a gunfight for a necessary conversation.

The performances, particularly Bautista’s, salvage the film from becoming a standard-issue thriller. Bautista continues to prove himself one of the most empathetic presences in modern action cinema. He occupies the screen not with the swagger of an invincible hero, but with the posture of a man burdened by the knowledge that he cannot save everyone. His chemistry with Bobby Cannavale, playing his partner, provides a necessary anchor, grounding the film’s more flighty plot points in a weary, lived-in camaraderie.

Ultimately, *Trap House* is a fascinating, imperfect examination of legacy. It asks what we pass down to our children when our profession is war. The answer, Dowse suggests, is not just the skills to survive, but the trauma that necessitates them. The film may not fully escape the trappings of its genre, but in its quietest moments, it manages to say something loud and clear about the cost of living a double life. It is a reminder that in the war on drugs, the first casualty is often the innocence of the home.