Sympathy for the RebelTo adapt Neil Gaiman is to invite a specific kind of trouble. His work, characterized by a dreamlike, literary density, rarely survives the transition to the screen with its soul intact. When *Lucifer* premiered in 2016, stripped of Gaiman’s metaphysical grandeur and repackaged as a police procedural, it seemed destined for the graveyard of high-concept failures. Yet, the series defied its own initial mediocrity, surviving a cancellation by Fox and a resurrection by Netflix, to become a surprisingly poignant meditation on free will and the possibility of change. It is a show that hides its theological dissertation inside a campy, decadent, and often silly crime drama.

Visually, *Lucifer* is a study in gloss. The Los Angeles it depicts is not a city but a mood board of neon-lit noir—sleek, expensive, and perpetually nocturnal. The nightclub "Lux" serves as the series’ visual anchor, a space of hedonism where the lighting is always low and the whiskey always amber. But the directors use this slick aesthetic as a trap. We are lured in by the "sex and violence" promise of the genre, only to be ambushed by the intimacy of the close-up. The camera lingers on Tom Ellis’s face, searching for the cracks in his devil-may-care armor. The visual language shifts from the chaotic wide shots of crime scenes to the claustrophobic, static framing of Dr. Linda Martin’s therapy office. It is here, in these quiet, clinical frames, that the show’s true battles are fought—not against demons, but against self-loathing.

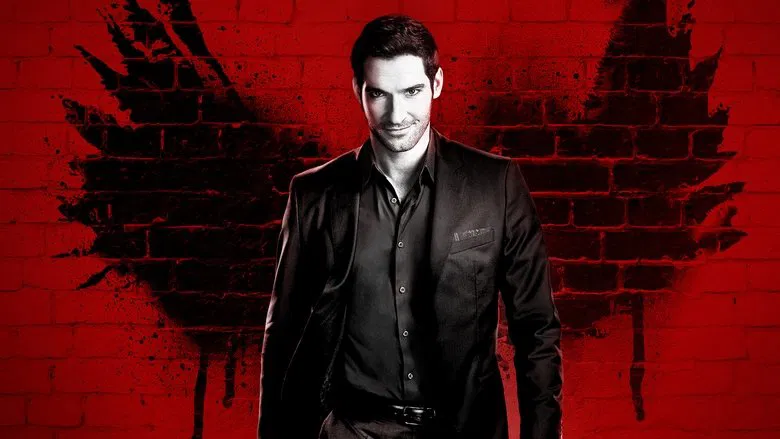

At the heart of the series is a performance of deceptive difficulty by Tom Ellis. It would have been easy to play the Devil as a mustache-twirling villain or a brooding anti-hero. Ellis instead chooses to play him as a petulant, wounded child with the power of a god. He is charming, yes, but his charisma is a defense mechanism. The central conflict of the series is not whether Lucifer will help Detective Chloe Decker catch the killer of the week; it is whether Lucifer can escape the narrative imposed upon him by his Father. The show asks a radical question: If the Devil is merely playing a role assigned to him by God, is he actually evil? Or is he the ultimate victim of cosmic determinism?

The procedural element—the "cop show" chassis that so many critics initially dismissed—turns out to be essential to this inquiry. By forcing the Devil to solve mundane human murders, the show grounds the celestial in the terrestrial. Lucifer learns humanity not through grand gestures, but through the petty grievances and small tragedies of the people he encounters. His partnership with Chloe Decker (Lauren German) evolves from a celestial curiosity into a mirror that reflects his own capacity for goodness. It is a slow-burn romance that serves as a theological argument: love is the only force capable of rewriting one’s nature.

Ultimately, *Lucifer* triumphs because it takes the oldest villain in western literature and grants him the right to therapy. It suggests that redemption is not a destination but a grueling, repetitive process of self-examination. The show posits that "Hell" is not a place of fire and brimstone, but a loop of our own guilt, a prison we build for ourselves and keep locked from the inside. In an era of television obsessed with grim anti-heroes who spiral downward, *Lucifer* dared to tell a story about the difficult, awkward, and often hilarious climb up. It is a series that started as a joke and ended as a prayer for the broken.