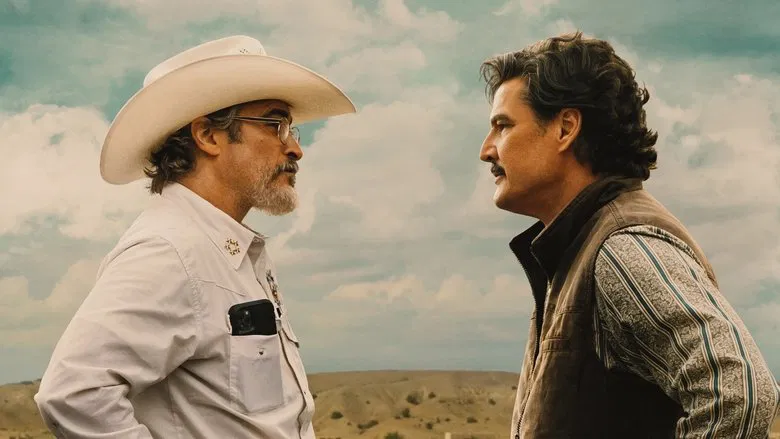

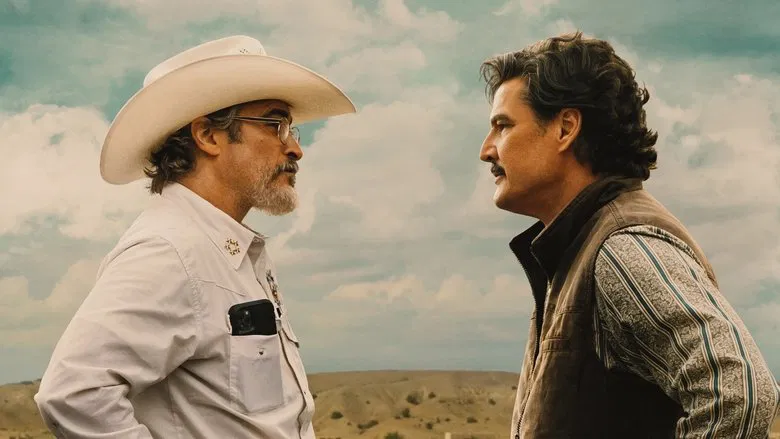

The Weight of SilenceThere is a moment in Ari Aster’s *Eddington* that captures the precise, suffocating texture of the year 2020 better than any newsreel. Two men, Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix) and Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal), stand at a barbecue in the New Mexico desert. They are not arguing about politics or pandemics, but wordlessly grappling over the volume knob of a stereo playing Katy Perry’s "Firework." It is a scene of profound, absurd pettiness—a microcosm of a society that has lost the ability to communicate, replacing dialogue with a sheer, brute exertion of will.

In *Eddington*, Aster pivots from the folk horror of *Midsommar* and the Freudian nightmare of *Beau Is Afraid* to a genre that feels deceptively grounded: the Western. But make no mistake, this is a landscape of terror. The film, set in May 2020, uses the isolation of the New Mexico desert to mirror the psychological quarantine of the American mind. The horror here isn't a pagan cult or a demon; it is the breakdown of shared reality. Aster argues that when a community fractures into "bubbles of certainty"—fueled by algorithms and anxiety—the result is a form of violence far more insidious than a gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

Visually, the film is a masterwork of contradiction. Cinematographer Darius Khondji (*Se7en*, *Uncut Gems*) rejects the panoramic freedom usually associated with the Western. Instead, he shoots the desert with a claustrophobic intensity, using a 1.85:1 aspect ratio that boxes the characters in. The heat ripples off the pavement not like a natural phenomenon, but like a glitch in the simulation. The looming construction of an AI data center on the horizon serves as a modern monolith, a cold, humming tombstone for the analog world the characters are desperately trying to defend or destroy.

The human tragedy at the center of this satire is anchored by Joaquin Phoenix. His Joe Cross is a man literally and metaphorically wheezing for air. Afflicted with asthma in the middle of a respiratory pandemic, Joe’s refusal to wear a mask is less a political statement than a pathetic grasp for control over his own failing body. Phoenix plays him with a squeaky, unraveling intensity that makes him impossible to hate but painful to watch. He is a man being hollowed out by his own impotence, watching his wife (a chillingly detached Emma Stone) drift toward the digital embrace of a viral grifter (Austin Butler).

What *Eddington* exposes is the fragility of the "social contract." The film’s violence, when it inevitably erupts, feels clumsy and unheroic—a mess of confusion rather than a choreographed ballet. Aster refuses to let us enjoy the bloodshed. By stripping the Western of its mythic grandeur and replacing it with the banality of Twitter-fueled paranoia, he forces us to look at the ugly, jagged edges of our current cultural moment.

Ultimately, *Eddington* is a bleak diagnosis of a terminal condition. It suggests that our addiction to conflict has become our only way of feeling alive. It is a difficult, abrasive work that offers no easy answers, only a mirror held up to a society that would rather burn down the saloon than share a drink with a neighbor. In Aster’s American West, the sun isn’t setting; it’s simply burning everything away.