✦ AI-generated review

The Geometry of Vengeance

In the geography of revenge cinema, the path is usually linear: a wrong is committed, a hero rises, and retribution is delivered with satisfying finality. But in Park Chan-wook’s 2003 masterpiece *Oldboy*, the second installment of his celebrated Vengeance Trilogy, the path is a circle—a tightening noose that strangles both the victim and the victor. While the film is frequently cited for its stylized violence and that infamous narrative detonation in the final act, to view it merely as a shock-thriller is to miss its profound, operatic tragedy. This is not a film about getting even; it is a film about the impossible weight of memory.

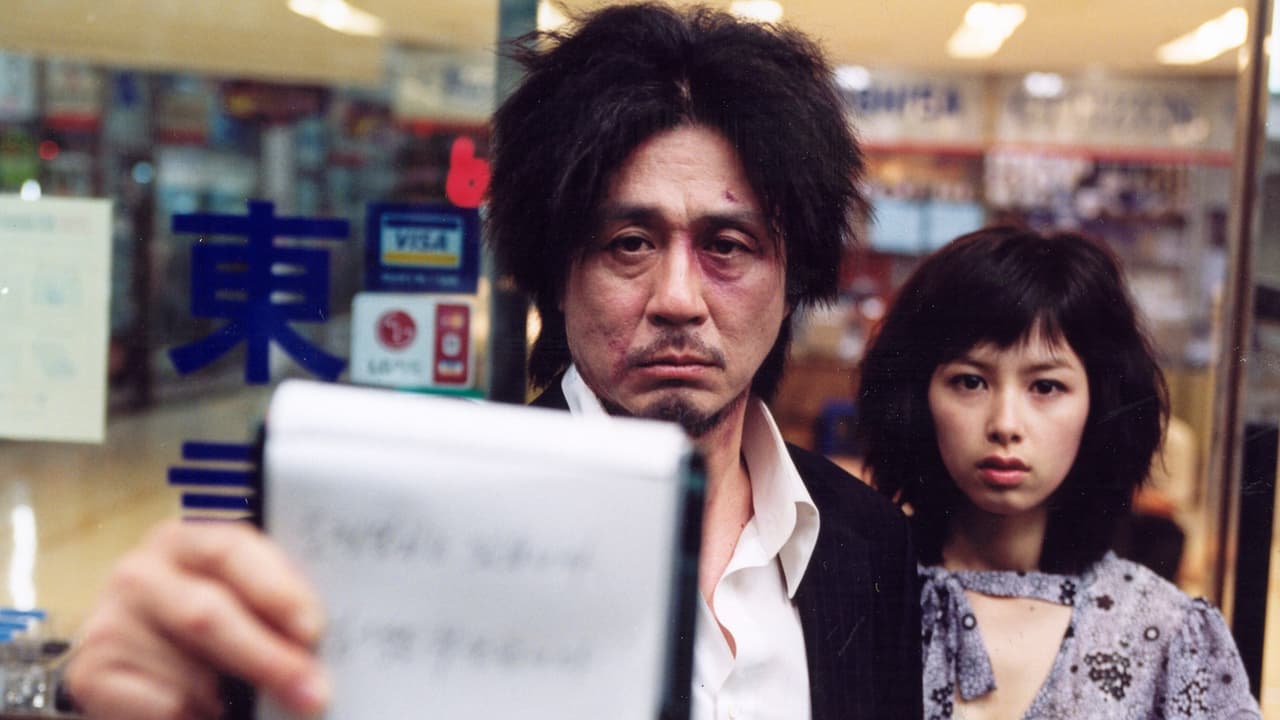

Park’s direction transforms the screen into a claustrophobic canvas, utilizing a sickly palette of moss greens and blood reds to externalize the decay of Oh Dae-su’s soul. Dae-su, played with feral intensity by Choi Min-sik, is a man who has been hollowed out by fifteen years of unexplained confinement. When he is released, he is less a man than a loaded weapon. Yet, Park refuses to let the audience enjoy the violence as mere spectacle.

The celebrated "corridor fight"—a single-take, side-scrolling sequence where Dae-su battles a hallway full of thugs with a hammer—is a masterclass in visual storytelling not because it is "cool," but because it is exhausted. There are no quick cuts to hide the fatigue. We see Dae-su winded, hurt, and desperate. It strips away the glamour of the action hero, leaving only a pathetic, sweating animal fighting for breath. The violence is not empowering; it is labor.

However, the physical brutality pales in comparison to the film’s psychological architecture. The antagonist, Lee Woo-jin, is not a villain in the traditional sense, but an architect of sorrow who understands that true destruction requires not death, but the corruption of the soul. The film’s central question isn't "Who imprisoned me?" but "Why was I released?" The answer reveals a narrative rooted in the grand tradition of Greek tragedy. Like Oedipus, Dae-su is the detective investigating his own crime, sprinting toward a truth that will obliterate him.

The film's climax, involving a pair of scissors and a severed tongue, is perhaps one of the most painful scenes in modern cinema, yet it contains no combat. It is a moment of total abasement, where the "monster" Dae-su has become begs not for his life, but for the preservation of a secret. Here, Park argues that the ultimate weapon is not a hammer, but the truth. The revelation of the incestuous taboo is not deployed for cheap shock value; it is the structural pillar that collapses the entire moral universe of the characters.

Ultimately, *Oldboy* serves as a grim meditation on the futility of looking backward. The final shot—a precarious smile in a snowy landscape—is hauntingly ambiguous. Has the hypnosis worked, granting Dae-su the bliss of ignorance? or is the smile a mask for a man who has chosen to live in hell rather than face reality? Park offers no absolution. He leaves us with the unsettling realization that vengeance acts like a mirror: stare into it long enough, and you will lose the ability to recognize yourself.