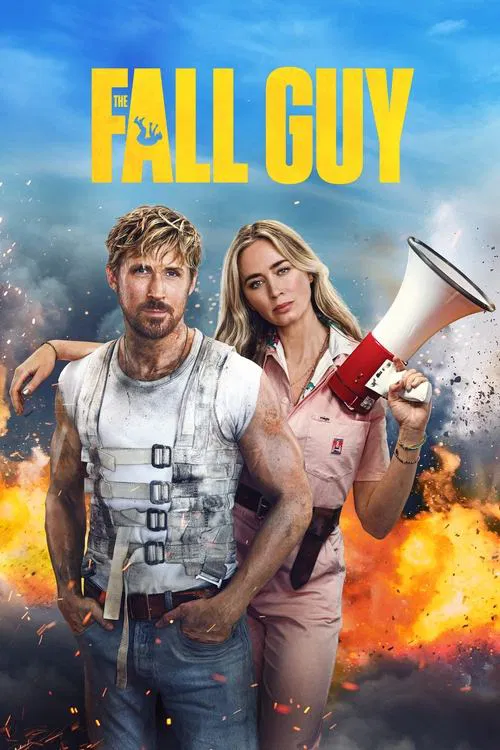

The Invisible Art of FallingThere is a cruel irony in the life of a stunt performer: the better they do their job, the less you believe they exist. They are the ghosts in the machine of cinema, suffering concussions and broken bones so that a movie star can look invincible on a poster. David Leitch’s *The Fall Guy* is not merely an action comedy or a reboot of a dusty 1980s TV show; it is a riotous, neon-drenched act of unionizing. It is a director screaming through a megaphone that the people who bleed for our entertainment deserve to be seen, even if their profession demands they remain invisible.

Leitch, a former stunt double for Brad Pitt who pivoted to directing (*Atomic Blonde*, *Bullet Train*), films this world with the specific, bruising affection of an insider. The visual language here is kinetic but grounded. Unlike the weightless, pixelated chaos of modern superhero fare, the action in *The Fall Guy* carries the heavy thud of gravity. When Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) hits a wall, you feel the wind get knocked out of him. Leitch uses wide angles and long takes not just to show off choreography, but to prove that a human body is actually occupying that space.

At the center of this bruising ballet is a romance that feels surprisingly tender. Colt is a man whose entire identity is built on durability, yet he is emotionally shattered by a breakup with camera operator-turned-director Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt). Gosling, arguably cinema’s most charismatic minimalist, finds a beautiful vulnerability here. He plays Colt not as a swaggering hero, but as a working-class anxiety ball who just happens to be able to fall 12 stories without dying.

The film’s most electric scene isn’t a car chase, but a conversation. Colt and Jody argue about their failed relationship over megaphones across a busy film set, disguising their heartbreak as directorial notes for a sci-fi scene. It is a perfect metaphor for the film industry itself: the messy, painful reality of human connection buried under layers of artifice and logistics. Blunt matches Gosling beat for beat, turning Jody into more than just a prize to be won; she is the creative force trying to hold the chaos together.

If the film stumbles, it is in its third act, where the plot—a conspiracy involving a missing movie star (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, having a ball as a Matthew McConaughey-esque narcissist)—becomes overly busy. The narrative mechanics sometimes creak under the weight of the spectacle. However, Leitch saves it with a meta-textual finale that literally weaponizes the tools of the trade—prop cars, pyrotechnics, and crash mats—to defeat the villains. It suggests that the "fake" world of movies is the only place where these characters can find real justice.

*The Fall Guy* ultimately serves as a melancholy reminder of a fading era of practical filmmaking. In a summer often dominated by digital sludge, Leitch has delivered a film that smells like gasoline and sweat. It is a joyous, bone-crunching argument that while CGI can create dragons, it can never replicate the thrill of a human being risking it all for the perfect shot.