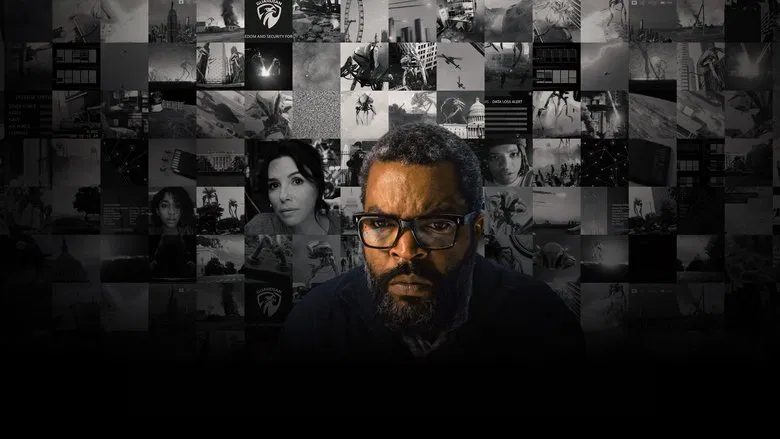

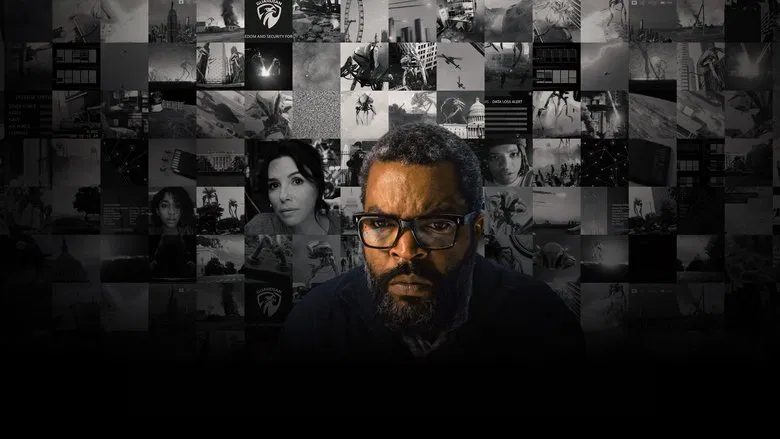

The Algorithm of ApocalypseThere is a moment early in Rich Lee’s *War of the Worlds* where Will Radford (Ice Cube), a Department of Homeland Security analyst, uses state-of-the-art government surveillance tech not to track terrorists, but to monitor his pregnant daughter’s heart rate and critique her dietary choices. It is a scene intended to establish paternal concern, yet it inadvertently reveals the film’s true horror: not the Martian tripod, but the unblinking, invasive eye of the screen itself. In this 2025 adaptation, H.G. Wells’ seminal nightmare of colonization has been flattened—quite literally—into a "Screenlife" desktop thriller, a format that trades cinematic grandeur for the claustrophobic anxiety of a Zoom call that never ends.

The "Screenlife" genre, pioneered by films like *Unfriended* and *Searching*, relies on the conceit that the entire narrative unfolds within the boundaries of computer monitors and smartphone displays. When executed well, it captures the frantic fragmentation of modern life. However, under Lee’s direction—he is a veteran of music videos making his feature debut here—the technique feels less like an artistic choice and more like a budget-conscious straitjacket. The film, reportedly shot during the height of pandemic isolation and shelved for years before this quiet release, suffers from a static visual language. We watch Will Radford watch the world end. The result is a strange paradox: a global cataclysm rendered with the emotional distance of a buffering YouTube video.

The visual landscape creates a suffocating sense of reality, but not the kind the filmmakers intended. The alien invasion, once the ultimate metaphor for imperialist hubris, is reduced to pixelated glitches and low-resolution security feeds. When the tripods finally descend, they are often relegated to background windows or shaky FaceTime connections, robbing the audience of awe. We are not witnessing the fall of civilization; we are scrolling past it. The film attempts to comment on the surveillance state—Will is part of the machine that watches us—but the critique collapses under the weight of its own product placement. In a narrative turn that borders on the surreal, the climax hinges on the tactical use of an Amazon delivery drone, transforming a fight for survival into a ninety-minute commercial for the very corporate omnipotence the script feigns to mistrust.

At the center of this digital storm is Ice Cube, an actor capable of profound charisma and intensity (recall *Boyz n the Hood* or *Three Kings*). Here, he is stranded. Acting against a webcam requires a specific kind of subtle, reactive performance; instead, Radford is often reduced to shouting at loading bars and barking orders into the void. The human core of the story—the estranged family dynamic involving his daughter (Iman Benson) and gamer son (Henry Hunter Hall)—feels like a algorithmically generated subplot, inserted to provide stakes that the pixelated carnage fails to generate. We see their faces in rectangular boxes, but their fear never pierces the glass. The emotional truth is buried beneath layers of interface, lost in a sea of notifications and pop-ups.

Ultimately, *War of the Worlds* (2025) serves as an accidental time capsule of a specific cultural anxiety—not of aliens, but of our own digital entrapment. It inadvertently asks a terrifying question: If the world were ending, would we look up at the sky, or would we just refresh the feed? By filtering the apocalypse through the lens of a desktop, the film strips the end of days of its tragedy, leaving us with only the user interface of catastrophe. It is a film that demands we log off, not because of the terror it inspires, but because the connection has simply timed out.