✦ AI-generated review

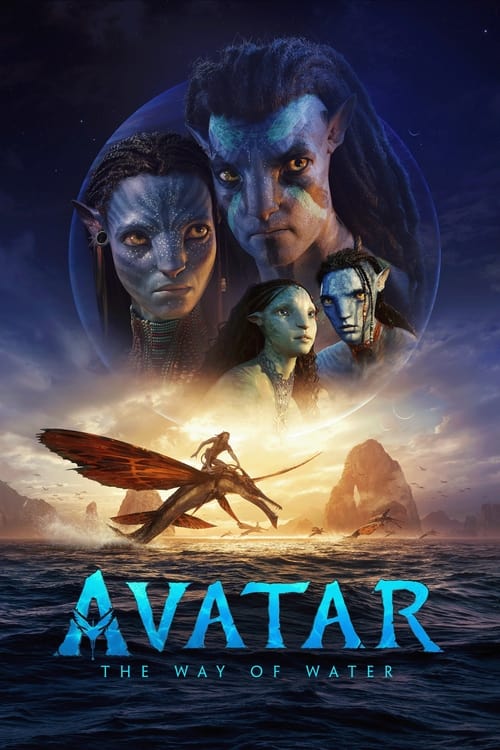

The Architecture of Awe

In an era of cinema defined by self-aware irony and meta-commentary, James Cameron remains a steadfast believer in the uncool power of sincerity. He does not wink at the audience; he demands they open their eyes wider. *Avatar: The Way of Water* (2022) is not merely a sequel to the highest-grossing film of all time; it is a defiant assertion that the blockbuster can still be a spiritual experience. While the narrative occasionally buckles under the weight of its own earnestness, the film succeeds as a triumph of texture over text, inviting us not just to watch a story, but to inhabit a living, breathing ecosystem.

Cameron’s transition from the bioluminescent forests of the Omatikaya to the sun-drenched reefs of the Metkayina is more than a change of scenery—it is a shift in sensory language. The director, a lifelong thalassophile who has arguably spent more time in submersibles than on red carpets, treats the ocean not as a backdrop, but as a sovereign entity. The visual fidelity here is suffocatingly real. The water does not behave like a computer simulation; it has weight, turbidity, and peril. When the characters submerge, the sound design drops into a muffled, amniotic hum, forcing the audience to hold their breath in sympathy. This is not "escapism" in the cheap sense; it is immersion so total it borders on the narcotic.

At the heart of this aquatic opera lies a shifting dynamic from the first film’s colonial resistance to a more intimate, claustrophobic struggle: the burden of fatherhood. Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) is no longer the white savior freedom fighter; he is a terrified patriarch, paralyzed by the fear of losing what he has built. This fear transforms him into a rigid military commander within his own home, alienating his sons.

The film finds its true emotional anchor not in the explosions, but in the subplot involving Lo’ak (Britain Dalton), the rebellious middle son, and Payakan, an outcast Tulkun (a hyper-intelligent whale-like creature). Their bond serves as a silent rebuke to the human antagonists. While the "Sky People" see the Tulkun only as biological resources to be harvested—a critique of capitalist extraction portrayed with gut-wrenching brutality—Lo’ak sees a soul. The scene where Lo’ak removes a harpoon from Payakan’s fin is a masterclass in visual storytelling; no dialogue is needed to convey the transfer of trust between two species scarred by violence. It is in these quiet moments that Cameron’s ecological plea feels most profound: we destroy nature because we refuse to speak its language.

Critically, the film is not without its stumbling blocks. The dialogue often resorts to utilitarian military jargon or teenage slang that feels jarringly terrestrial. The "white savior" tropes of the first film still linger, even if they are complicated by the Sully family’s mixed heritage and their refugee status among the reef clans. Yet, to dismiss the film for its narrative simplicity is to misunderstand its purpose. *The Way of Water* operates like a lucid dream or a mythic cycle; its power lies in the universality of its archetypes—the prodigal son, the vengeful ghost, the dying mother.

Ultimately, *Avatar: The Way of Water* stands as a monolith of traditional cinematic values built with futuristic tools. It asks us to endure a three-hour meditation on grief, water, and family, betting that the sheer majesty of its construction will hold our attention. In a landscape of disposable entertainment, Cameron has built a cathedral. You may critique the sermon, but you cannot deny the glory of the stained glass.