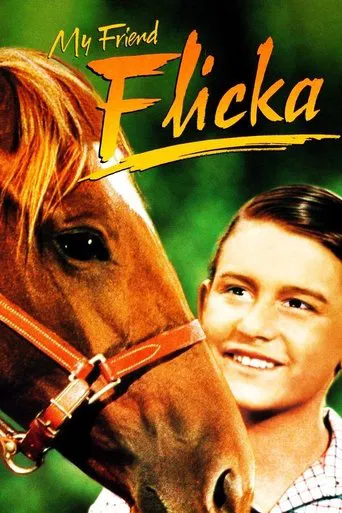

The Shadow in the DunesIn the landscape of Dutch cinema, director Steven de Jong has carved out a specific, pastoral niche. He is a filmmaker who understands that the Dutch landscape—particularly the flat, wind-swept northern provinces—is not merely a backdrop, but a participant in the narrative. With *Penny’s Shadow* (2011), de Jong ostensibly adapts the ethos of the popular "Penny" magazine culture—a brand synonymous with equestrian passion for young girls. Yet, to dismiss this film as a mere magazine tie-in would be a disservice to its craft. At its core, this is a somber, atmospheric melodrama about the geography of grief, set against the stark, beautiful desolation of the island of Ameland.

The film follows Lisa, a teenager with an intuitive connection to horses, who travels to Ameland for a vacation. There, she encounters Kai and his father, who run a holiday farm shadowed by a past tragedy. A black stallion, Shadow, is kept locked away, a living monument to the accident that claimed Kai’s mother.

Visually, de Jong exploits the isolation of the Wadden Sea island to tremendous effect. The cinematography eschews the bright, saturated colors typical of the genre in favor of a more naturalistic, sometimes melancholic palette. The endless dunes and the imposing lighthouse serve as visual metaphors for Kai’s internal state: vast, empty, and fortified against intrusion. The sequences filmed in the "forbidden" zones of the stable are claustrophobic, contrasting sharply with the liberation found on the open beach. The horse, Shadow, is filmed not just as an animal to be tamed, but as a creature of mythic terror and beauty—a physical manifestation of the trauma that Kai refuses to process.

The narrative arc follows the familiar beats of the "horse whisperer" trope—the outsider who sees the soul within the beast—but the script imbues the human conflict with genuine weight. Lisa is not simply training a horse; she is dismantling a family’s architecture of silence. The tension is palpable not because of the physical danger of the horse, but because every step forward with Shadow feels like a betrayal of the memory of the mother.

The film’s climax, involving a lifeboat demonstration, is a technical high-wire act that merges the island’s cultural history with the film’s personal stakes. It is here that de Jong’s direction shines, balancing the chaotic action of the rescue with the intimate emotional breakthrough required of Kai. The actors, particularly the young leads, handle the material with a sincerity that grounds the more melodramatic elements. They play the silence as effectively as the dialogue, letting the roar of the surf fill the gaps where words fail.

Ultimately, *Penny’s Shadow* succeeds because it treats its target audience with respect. It acknowledges that the bond between human and animal is often a proxy for the connections we struggle to make with one another. It transforms a summer holiday story into a poignant meditation on letting go, suggesting that the only way to escape the shadow is to ride directly into the light.