✦ AI-generated review

The Green Iconoclast

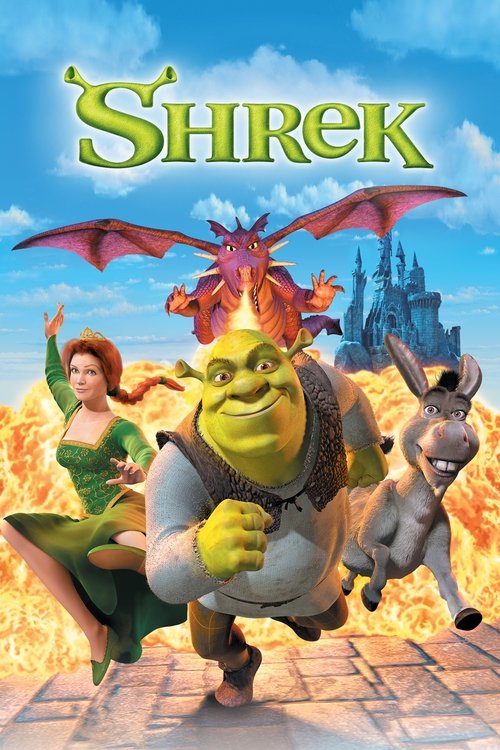

The most significant sound effect in modern animation history is the sound of a page tearing. In the opening seconds of *Shrek* (2001), the titular ogre reads the closing lines of a traditional fairy tale, laughs, rips out the page, and uses it for hygiene. With that singular, scatological gesture, directors Andrew Adamson and Vicky Jenson didn't just start a movie; they issued a manifesto. *Shrek* was not merely a comedy; it was a cultural insurrection, a calculated deconstruction of the Disney renaissance that had dominated the previous decade. Yet, beneath its layers of irony and Smash Mouth needle-drops, it managed to achieve something the films it mocked often missed: profound emotional honesty.

To understand *Shrek*, one must first acknowledge its weaponized context. Produced by DreamWorks, the studio co-founded by Jeffrey Katzenberg after his acrimonious departure from Disney, the film is often viewed through the lens of corporate vengeance. The villain, Lord Farquaad—a diminutive tyrant obsessed with a sanitized, perfect world—is widely interpreted as a caricature of Disney CEO Michael Eisner. His kingdom of Duloc is a sterile theme park where conformity is law and "It’s a Small World" is the anthem of oppression. But to reduce the film to an executive grudge match is to ignore its artistic triumph. Adamson and Jenson utilized the medium of computer animation—then still in its uncanny adolescence—to create a world that felt tactile, messy, and lived-in. Unlike the polished marble of traditional fairy tales, Shrek’s swamp is a place of mud, earwax, and isolation. The visual language reinforces the narrative thesis: reality is gross, and that is where true beauty hides.

The film’s brilliance lies in its protagonist’s reluctance. Shrek (voiced with a distinct Scottish weary warmth by Mike Myers) is not a hero seeking glory; he is a marginalized recluse seeking silence. He is the monster who has read the script and knows he is supposed to die at the end of Act Three. His journey is not about slaying the dragon, but about unlearning the internalized hatred that society has projected onto him. When he tells his unwanted companion, Donkey (a manic, brilliant Eddie Murphy), that ogres are like onions because they have "layers," it is a defense mechanism. He is protecting a soft core with a prickly, pungent exterior.

This theme of self-acceptance reaches its zenith in the character of Princess Fiona (Cameron Diaz). The film’s most radical subversion is not its pop-culture references, but its resolution. In a genre conditioned to reward goodness with physical beauty, *Shrek* dares to do the opposite. When the curse is broken and Fiona takes "love's true form," she does not revert to the lithe, human princess. She remains an ogre. The film argues that the "happy ending" isn't becoming acceptable to the world; it is finding the one person who makes you feel that you already are.

There is a moment in the second act, set to a cover of Leonard Cohen’s "Hallelujah," that strips away the irony entirely. We see Shrek and Fiona, separated by misunderstanding, staring at the moon in their respective solitudes. It is a sequence of aching melancholy that anchors the film's zany energy. It proves that *Shrek* loves its characters more than it hates its targets.

Two decades later, *Shrek* is often meme-ified into oblivion, its legacy complicated by a deluge of inferior sequels. However, the original remains a tight, disciplined piece of storytelling. It was a necessary corrective—a film that taught a generation of children that Prince Charming might be a narcissist, that the "monster" might be the only honest guy in the room, and that you don't need to change your skin to find your story.