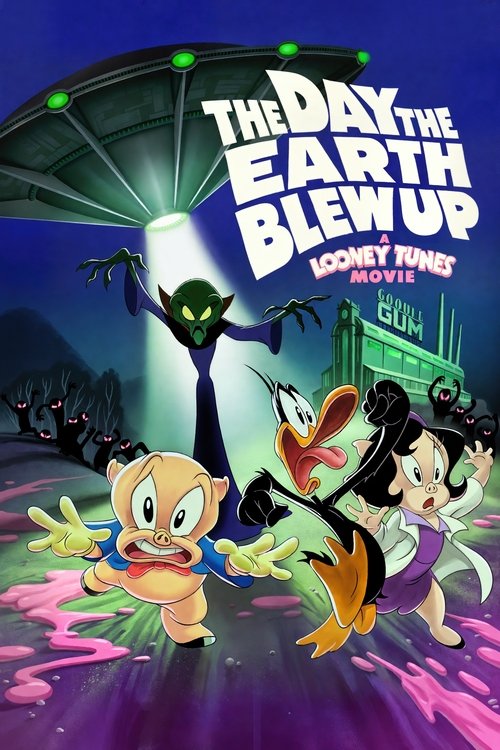

The Weight of LevityIn an era where "intellectual property" is often treated as a grim custodial duty—a checklist of assets to be managed, rebooted, and sterilized—*The Day the Earth Blew Up: A Looney Tunes Movie* arrives like a defiant, anarchic scream. It is a film that exists against the odds, salvaged from the scrapheap of a corporate merger that famously deleted the fully completed *Coyote vs. Acme*. Directed by Peter Browngardt, this is not merely a "content drop" for a streaming algorithm; it is a delirious, hand-drawn restoration of the id. It reminds us that cinema, even in its silliest forms, thrives not on brand synergy, but on the specific, undeniable rhythm of chaos.

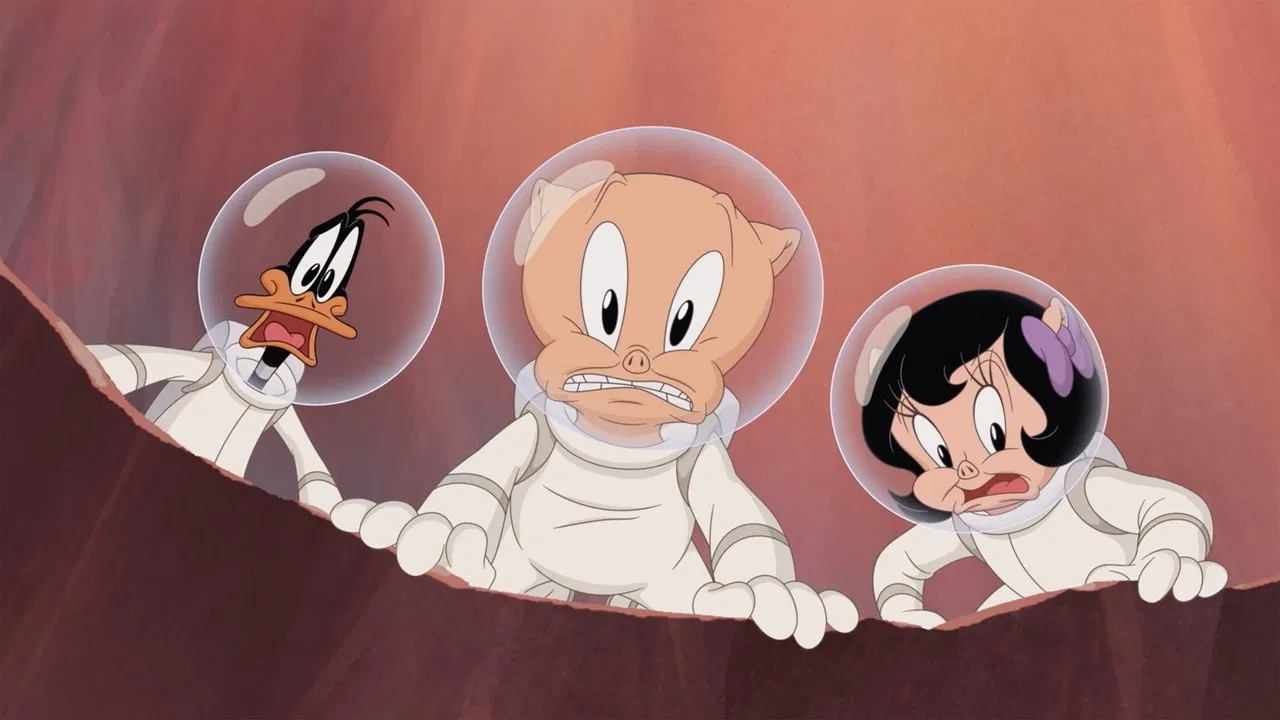

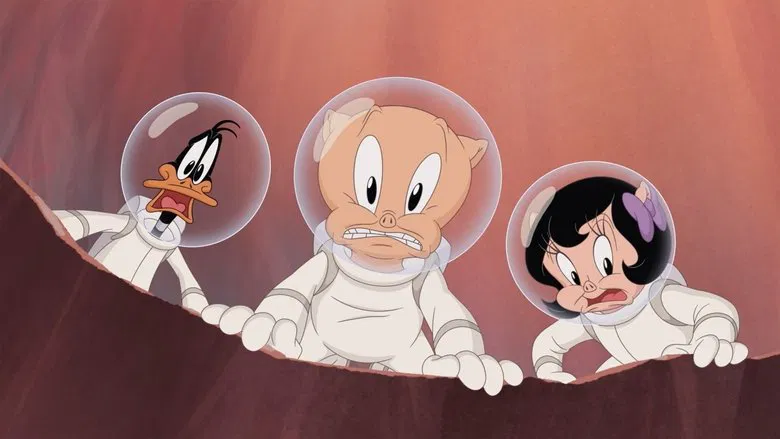

Visually, Browngardt and his team have rejected the clean, vector-based perfection of modern digital animation in favor of something far more tactile and erratic. The film draws heavily from the lineage of Bob Clampett, the Warner Bros. director known for his rubbery, hyper-expressive style, rather than the more disciplined geometry of Chuck Jones. Characters don't just move; they distort. Daffy Duck is not a solid object here; he is a nervous system constantly on the verge of total collapse, his beak twisting into impossible knots of anxiety and greed.

The animation possesses a manic energy that feels almost dangerous, a quality absent from the sanitized *Space Jam* sequels. The background art, reminiscent of the mid-century modern aesthetic of the 1950s, provides a lush, painterly contrast to the absolute mayhem in the foreground. It is a visual language that respects the audience enough to be ugly, grotesque, and beautiful all at once.

At its core, however, *The Day the Earth Blew Up* is a story about the fragility of domesticity. By casting Porky and Daffy as roommates—and essentially brothers—the film taps into a profound emotional truth about their dynamic. Porky is the superego, the weary stutterer trying to maintain order in a world that refuses to make sense. Daffy is the unbridled id, a creature of pure impulse who inadvertently saves the world simply by being too chaotic to control.

The plot, involving a mind-controlling bubble gum alien invasion, is secondary to the "roommate drama." There is a scene where the duo faces eviction that hits with surprising emotional weight, grounded in the terrifying reality of losing one's home. Yet, the film never wallows; it transmutes this anxiety into kinetic violence. When they take jobs at the local gum factory, the industrial machinery becomes a Chaplin-esque nightmare of automation, a perfect stage for their physical comedy to critique the drudgery of the working class without ever ceasing to be funny.

This film is a small miracle. In a landscape dominated by photo-realistic lions and focus-grouped superhero cameos, *The Day the Earth Blew Up* feels like a handmade explosive device. It proves that these characters are not "retro" icons to be dusted off, but living, breathing archetypes of human neurosis. It doesn’t just pay homage to the Golden Age of animation; it argues that the anarchy of the past is the only thing that can save us from the sterilized boredom of the present. It is loud, rude, and undeniably alive.