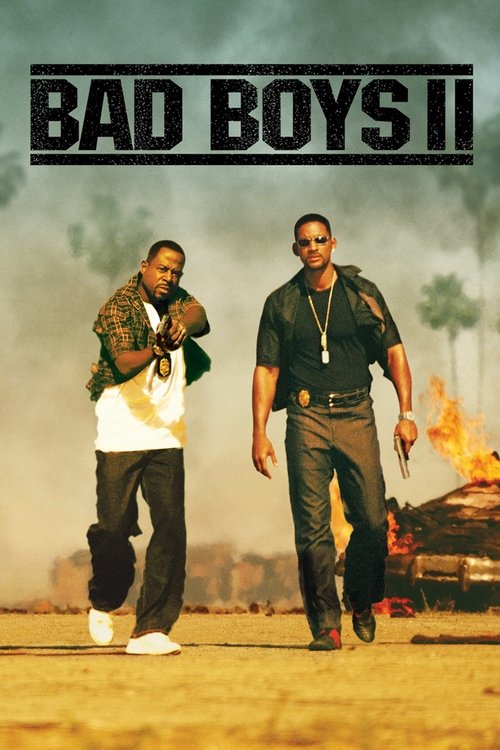

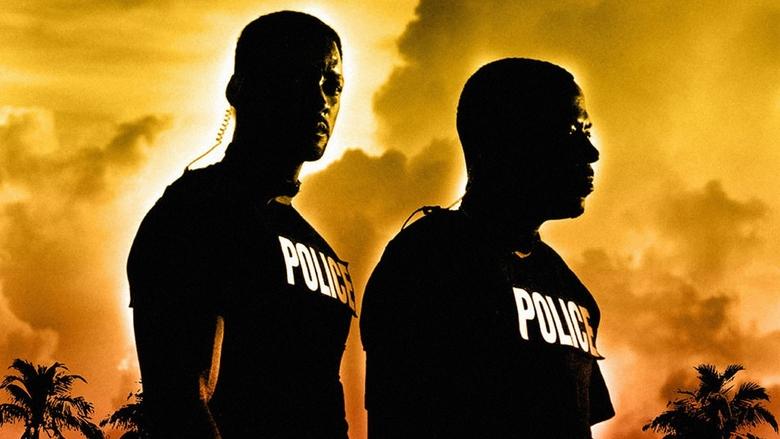

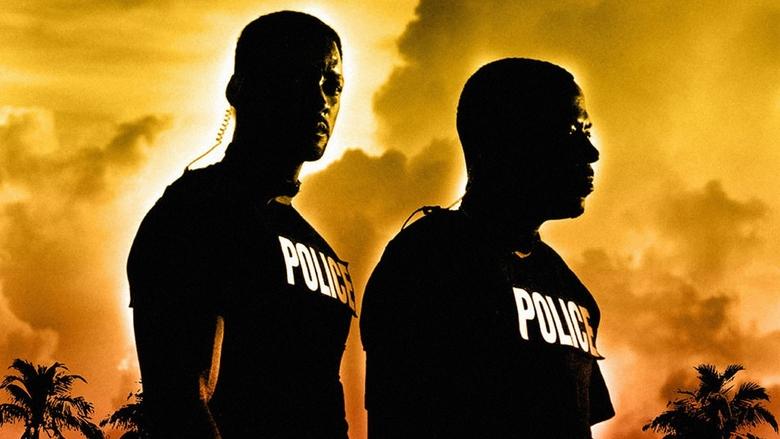

The Cinema of Scorched EarthIf cinema is a mirror reflecting the society that created it, *Bad Boys II* (2003) is a funhouse mirror held up to a fever dream of American excess. Directed by Michael Bay, this film is not merely a sequel to a buddy-cop hit; it is a manifesto of "Bayhem," a stylistic pivot where the director ceased chasing the prestige of *Pearl Harbor* and instead fully embraced a cinema of pure, unadulterated sensation. It is a film that does not just ask for your suspension of disbelief; it demands your submission to its noise, its speed, and its aggressive nihilism. To view it simply as an action movie is to miss its significance as a towering monument to the early 2000s' cultural id.

Visually, the film is a masterclass in technical virtuosity decoupled from physical reality. Bay’s camera is a restless predator, swooping low under spinning tires and orbiting sweating actors with a fetishistic intensity. The color palette is not natural; it is hyper-saturated, a world of neon blues and sunset oranges that makes Miami look less like a city and more like a hallucination of heat. The editing fractures space and time, prioritizing impact over geography. Nowhere is this more evident than in the infamous freeway chase, where a mortuary van spills corpses onto the road. The heroes, Detectives Mike Lowrey (Will Smith) and Marcus Burnett (Martin Lawrence), dodge the bodies with the same casual dexterity they use to dodge moral responsibility. It is a sequence of grotesque hilarity—"Looney Tunes" logic applied to a grim reality—that perfectly encapsulates the film’s unique tone: a high-gloss celebration of the macabre.

However, beneath the gloss lies a fascinatingly cruel heart. While the genre typically relies on the clear moral superiority of its protagonists, *Bad Boys II* presents its heroes as agents of chaos who are arguably more dangerous than the villains they pursue. The narrative, which sees the duo tracking an Ecstasy ring from Miami to Cuba, eventually collapses into a startling display of interventionist fantasy. The climax, involving an unauthorized invasion of Cuba and a Hummer tearing through a hillside shantytown, is perhaps the film’s most critical text. As shacks disintegrate under the wheels of the protagonists' vehicle, the film invites us to cheer for the destruction of the impoverished "other" in service of the American hero’s victory. It is a post-9/11 anxiety dream rendered in high-definition, where the only solution to complexity is overwhelming firepower.

Yet, despite—or perhaps because of—this cruelty, the film remains a singular achievement in action filmmaking. It possesses a relentless energy that modern blockbusters, often weighed down by green-screen sterility, fail to replicate. Smith and Lawrence operate at a frequency of manic improvisation that feels genuinely dangerous, their camaraderie the only stabilizing force in a universe spinning out of control. *Bad Boys II* is not a film that seeks to be loved for its humanity; it seeks to be awed for its scale. It is a jagged, loud, and unapologetically mean piece of pop art that captures a specific moment in history when the only way forward was to burn everything down and look good doing it.