✦ AI-generated review

The Nightmare of the Holiday Aisle

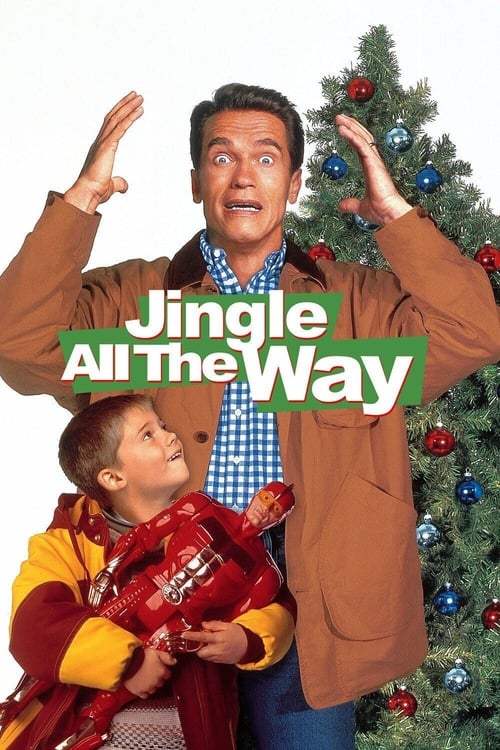

In the pantheon of 1990s cinema, few films capture the frantic, hyper-capitalist anxiety of the era quite like *Jingle All the Way*. Released in 1996, at the height of the Tickle Me Elmo craze, Brian Levant’s family comedy was dismissed by contemporary critics as a loud, slapstick vehicle for Arnold Schwarzenegger. Yet, viewing it through the lens of modern cynicism, the film transforms into something far more fascinating: a brightly colored, live-action cartoon that accidentally functions as a crushing satire of the American Dream. It posits a world where paternal love is measured exclusively in molded plastic, and the failure to consume is a moral failing.

Levant, a director whose oeuvre includes *The Flintstones* and *Beethoven*, applies a specific visual language here that can best be described as "suburban surrealism." The film is bathed in the flat, high-key lighting of a sitcom, yet the events that transpire are grotesque. The Minneapolis of *Jingle All the Way* is a dystopia disguised as a winter wonderland. We see this most vividly in the film's standout set piece: a warehouse raided by law enforcement, revealing an underground ring of counterfeit Santas. The imagery is almost Dantean—a smoke-filled, grimy underworld where the symbols of holiday cheer are revealed to be criminals exploiting desperate fathers. Levant shoots the action with a chaotic, kinetic energy that mirrors the internal panic of his protagonist, turning a simple shopping trip into a gladiatorial combat zone.

At the heart of this chaos is the struggle of Howard Langston (Schwarzenegger), a mattress salesman who has neglected his family for his career. The narrative explicitly conflates Howard’s redemption with his ability to acquire the "Turbo Man" doll. This is not merely a plot device; it is the film’s theology. Howard and his rival, the mailman Myron Larabee (played with manic intensity by Sinbad), are two sides of the same desperate coin. Myron is the id to Howard’s superego—unhinged, threatening, and keenly aware of the system's rigged nature. "We are being set up by the system!" Myron screams, a line that is played for laughs but rings with an uncomfortable truth. They are Sisyphus and Prometheus, damned to roam the Mall of America for eternity.

However, the film’s most subversive element is not the consumerist critique, but the character of Ted Maltin, played by the late, brilliant Phil Hartman. Ted is the "perfect" single dad next door—he bakes, he decorates, he parents effortlessly. In a standard family film, Ted would be a role model. In Levant’s twisted reality, Ted is the true villain: a predatory figure waiting for Howard to fail so he can encroach on his domestic space. Hartman plays the role with a slimy, passive-aggressive veneer that is genuinely unsettling. The horror of the film isn't that Howard might not get the toy; it's that he might be replaced by a man who has weaponized "nice guy" behavior to steal his wife.

Ultimately, *Jingle All the Way* collapses under the weight of its own commercial mandate. It cannot fully commit to its satirical edge because it must also sell merchandise (real-world Turbo Man dolls were, ironically, produced). The climax, which sees Howard literally becoming the superhero his son worships, suggests that the only way to be a good father is to become a living product. Despite this thematic surrender, the film remains a fascinating cultural artifact. It is a fever dream of 90s excess, a reminder that in the war for holiday joy, the first casualty is sanity.