The Man in the Mirror's ShadowBiopics of the divinely famous are often traps disguised as tributes. They promise to unveil the human being behind the icon, yet usually settle for a wax museum reenactment—mimicry mistaken for soul. Antoine Fuqua’s *Michael*, a colossal and technically dazzling undertaking, steps into this trap with both eyes open. It attempts to wrestle with the most electrically charged figure in modern pop culture, Michael Jackson, and while it succeeds in resurrecting the sheer kinetic energy of his performance, it ultimately flinches before the enigma of his life.

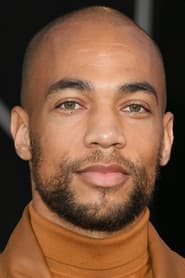

Fuqua, a director best known for the muscular grit of *Training Day* and *The Equalizer*, brings a surprising, almost operatic weight to the film’s visual language. Working with cinematographer Dion Beebe, he bifurcates the film’s aesthetic. The early years in Gary, Indiana, are shot with a grainy, suffocating intimacy—a sepia-toned pressure cooker where Joe Jackson (played with terrifying, stoic menace by Colman Domingo) forges a weapon out of his children. These scenes breathe. They feel sweaty and dangerous, grounding the myth in a painful reality of labor and stolen childhood.

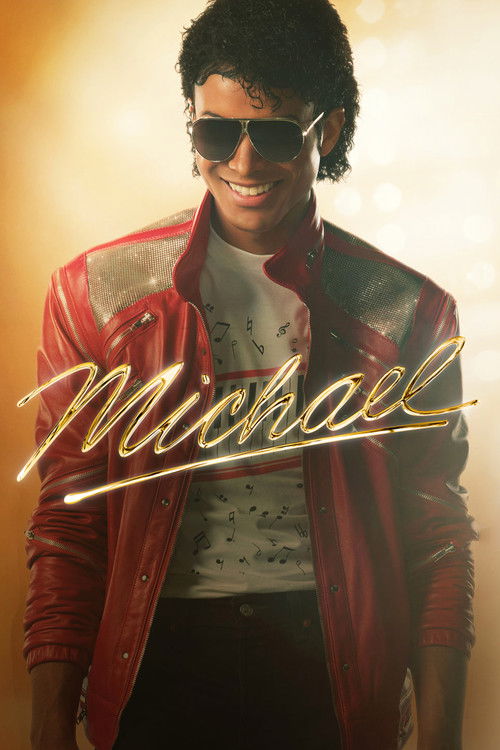

But as the film transitions into the neon-soaked excess of the 1980s, the visual palette shifts into a pristine, hyper-digital gloss that mimics the polished surface of Jackson’s own life. The recreation of the *Thriller* and *Bad* eras is uncanny, almost ghostly. Fuqua understands that for Jackson, the stage was the only place reality made sense. The concert sequences are not just musical numbers; they are filmed like religious ecstasies, suffocating in their grandeur.

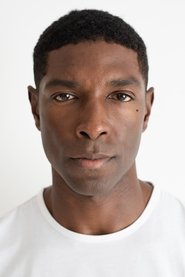

The gravitational center of the film is, of course, Jaafar Jackson. Casting a family member to play the patriarch is a gamble that risks nepotistic vanity, but Jaafar is a revelation of physical discipline. He does not just replicate the moves; he inhabits the skeletal, nervous energy of his uncle. The voice, the breathy hesitation, the sudden snaps of ferocity—it is a technical marvel of a performance. Yet, the script, penned by John Logan, often strands him behind the mask. We see the sweat, we see the pills, and we see the loneliness, but the film seems terrified to look him directly in the eye. Jaafar is excellent at playing "Michael Jackson the Superstar," but the film rarely lets him play the man dissolving inside the costume.

This reticence is the film's fatal flaw. By stopping its narrative scope largely before the most devastating controversies of the 1990s and 2000s fully metastasize, or by framing them strictly through the lens of a "persecuted genius," *Michael* feels curated. It humanizes the icon but sanitizes the tragedy. The "conversation" surrounding this film has rightfully centered on what it omits. In trying to protect the legacy, Fuqua and the estate have created a portrait that feels unfinished—a statue with the cracks filled in with gold.

Ultimately, *Michael* is a tragedy of isolation disguised as a celebration of genius. It is a loud, visually spectacular film about a man who lived in a deafening silence. Fuqua has built a magnificent cathedral for the King of Pop, but in refusing to fully light the darker corners of the sanctuary, he leaves us worshipping the image rather than understanding the man. It is a breathtaking show, but when the lights come up, the mystery remains entirely intact.