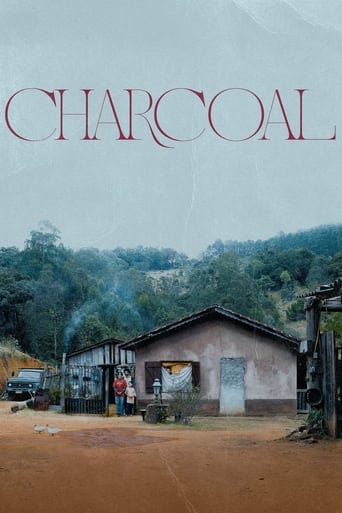

Ascending the Spire of GriefThere is a peculiar subgenre of cinema best described as "somatic horror." These films are less interested in the intellectual complexity of a plot and more concerned with hijacking the viewer’s autonomic nervous system. Scott Mann’s *Fall* (2022) is a brutally effective entry in this canon, a survival thriller that trades the claustrophobia of *Buried* or the aquatic dread of *47 Meters Down* for the paralyzing exposure of the open sky. While it wears the guise of a B-movie adrenaline rush, Mann’s film operates as a surprisingly potent metaphor for the vertigo of grief—the sensation that the ground has vanished, leaving you clinging to a rusting memory that can no longer support your weight.

The premise is stripped to its elemental bones. Becky (Grace Caroline Currey), drowning in alcohol and depression a year after witnessing her husband’s death in a climbing accident, is dragooned by her adrenaline-junkie best friend, Hunter (Virginia Gardner), into scaling the B-67 TV tower. This abandoned 2,000-foot needle in the Mojave Desert serves as the film’s antagonist, a monolith of oxidizing metal and whistling wind.

Mann’s visual language is the film’s greatest triumph. In an era dominated by weightless digital environments, *Fall* insists on a terrifying tactile reality. The camera lingers on the texture of the threat: the flaking paint, the vibrating guy wires, and the bolts that rattle in their loose sockets like chattering teeth. By filming on actual tower sections constructed on a mountain precipice, Mann captures the specific quality of light and the stomach-churning perspective of high-altitude exposure. The cinematography creates a paradoxical "agora-claustrophobia"—the characters have the entire sky around them, yet they are confined to a platform the size of a pizza box. Every drone shot that swirls around the women emphasizes their insignificance against the indifferent horizon.

However, the film attempts to be more than a technical exercise in inducing nausea. The script uses the ascent as a crucible for Becky’s internal stagnation. If her husband’s death was the initial fall, her year of mourning was the impact. Climbing the tower is framed as a therapeutic act, a way to conquer the trauma by literally rising above it. But as the ladder collapses and leaves them stranded, the film shifts from an adventure into a psychodrama. The revelation of a past infidelity between Hunter and Becky’s late husband adds a layer of interpersonal vertigo; just as the physical structure is rotting beneath them, so too is the foundation of their friendship.

This psychological fracture manifests most poignantly in the film's third act. Without spoiling the mechanical specifics of the twist, the narrative questions the reliability of the survival instinct itself. As dehydration and exhaustion set in, the film blurs the line between external reality and internal coping mechanisms. The dialogue, occasionally hampered by Gen Z caricatures in the first act, gives way to a grim, hallucinated silence. Becky’s journey becomes one of shedding dead weight—quite literally. The sequence involving a circling vulture is particularly grotesque and symbolic; to survive, Becky must consume the very thing waiting for her to die. She transforms from a passive victim of gravity into a primal force, willing to desecrate the dead to send a signal to the living.

Ultimately, *Fall* transcends its simple setup through sheer execution. It is a film that demands to be felt in the inner ear as much as seen with the eyes. While the emotional beats occasionally veer into melodrama, they are grounded by Currey’s desperate, physical performance. She sells the terror not just of falling, but of living when you have no way down. In the end, Mann suggests that survival isn't about conquering the fear of death, but about finding the savage will to keep gripping the ledge, even when your hands are bleeding.