The Weight of GreatnessThere is a moment in Justin Tipping’s *HIM* where the thud of a body hitting turf sounds less like a tackle and more like a gavel striking a desk. It is a sound of finality, of a contract being sealed not with ink, but with cartilage and bone. Tipping, who previously explored the jagged edges of masculinity in *Kicks*, returns here with a far more operatic ambition. Produced under the watchful eye of Jordan Peele’s Monkeypaw Productions, *HIM* attempts to deconstruct the American deity of the Quarterback. While it occasionally stumbles under the weight of its own metaphors, the film succeeds as a visceral, hallucinogenic scream about the price of immortality in a culture that demands human sacrifice for Sunday entertainment.

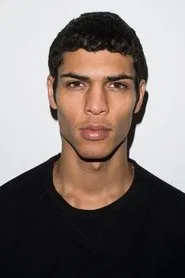

The narrative framework is deceptive in its simplicity. Cameron Cade (Tyriq Withers), a generational talent whose career is jeopardized by a brain injury, is invited to the fortress-like compound of his idol, the aging superstar Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans). What begins as a *Whiplash*-style mentorship quickly rots into folk horror. Tipping’s visual language is claustrophobic; he trades the expansive green of the gridiron for the sterile, suffocating reds and sterile whites of Isaiah’s compound. The cinematography treats the training facility not as a gym, but as a temple—or perhaps an abattoir. The camera lingers on the contortion of muscles and the ritualistic injection of fluids, blurring the line between medical science and occult liturgy.

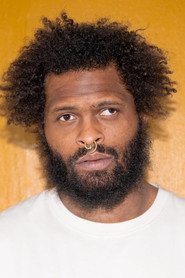

At the center of this fever dream is Marlon Wayans, delivering a performance of reptilian intensity. Known largely for comedy, Wayans here is a revelation, stripping away his usual manic energy to reveal a hollow, terrifying stillness. As Isaiah, he is a man who has cannibalized his own humanity to become a "god," a figure who views his successor not with pride, but with the hungry eyes of a vampire seeking a fresh vessel. His chemistry with Withers is electric, built on a foundation of reverence that slowly curdles into dread. Withers, for his part, anchors the film with a desperate physicality, his eyes conveying the terror of a young man realizing that his dreams are actually a digestive tract.

The film’s "conversation" has largely revolved around its third act, where the psychological tension explodes into literal Grand Guignol. Critics have argued whether the shift to supernatural horror undermines the social commentary on the exploitation of Black athletes. Yet, this criticism misses the point of the genre. Tipping isn’t making a documentary about the NFL; he is manifesting the internal psychological violence of the sport into external reality. The "GOAT" (Greatest of All Time) is not just a title here; it is a curse, a mantle passed down through blood and trauma. When the narrative unspools into madness, it is merely catching up to the absurdity of a system that asks young men to destroy their brains for the sake of a franchise owner’s profit margins.

Ultimately, *HIM* is a flawed but fascinating entry into the canon of "social thrillers." It may lack the surgical precision of *Get Out*, but it possesses a raw, kinetic energy that is impossible to ignore. It asks us to look at our heroes and wonder what parts of themselves they had to cut away to fit onto the pedestal. In the final, blood-soaked frames, Tipping suggests that in the coliseum of modern sports, there are no winners—only survivors, and the ghosts they carry with them.