The Gravity of a Second ChanceIn the collective memory of pop culture, the story of Will Smith—the fictionalized West Philly teenager, not the global superstar—is a neon-colored fable of luck. It is a sitcom intro rap, a catchy cadence about a "couple of guys who were up to no good," followed by a first-class ticket to a mansion. But Morgan Cooper’s *Bel-Air* (2022) asks a question that the original 90s sitcom, for all its charm, could only whisper: What if that "one little fight" wasn't a joke? What if it was a life-or-death trauma that exiled a young man from the only home he ever knew? By stripping away the laugh track, *Bel-Air* does not merely update a classic; it exhumes the anxiety buried beneath the comedy.

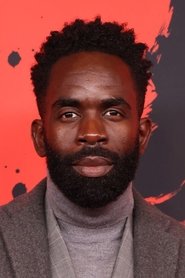

Visually, the series operates in a register of high-gloss claustrophobia. Cooper, who directs the pilot, uses the camera to emphasize isolation even amidst opulence. The sun-drenched aesthetic of Southern California is rendered not as a paradise, but as a blinding, over-exposed cage. The mansion is museum-like, cold and vast, contrasting sharply with the warm, kinetic energy of the Philadelphia streets shown in flashbacks. We see this visual tension most clearly in the way Will (played with magnetic vulnerability by Jabari Banks) moves through these spaces. In Philly, the camera is handheld, frantic, alive; in Bel-Air, it is static and composed, pinning him like a specimen in a glass case. The wardrobe choices further this narrative—Will’s Jordans and reversed cap aren't just fashion statements here; they are armor against a world that demands his assimilation.

The heart of the series, however, lies in its radical reimagining of the relationships, particularly the brotherhood between Will and Carlton. In the sitcom, Carlton was a lovable foil, a dance-move meme. Here, played by Olly Sholotan, he is a tragic figure of internalized pressure—a young Black man so desperate to fit into white elitism that he views his cousin not as family, but as an existential threat. The tension between them is no longer played for laughs; it is a Shakespearian struggle for the soul of the Banks legacy. This dynamic forces the audience to confront the cost of "making it." When Will arrives, he doesn't just disrupt a household; he holds a mirror up to a family that has polished away its Blackness to survive in a white world.

Ultimately, *Bel-Air* succeeds because it refuses to treat its source material as sacred scripture, but rather as a folklore that can be retold with new emotional stakes. It understands that the American Dream, for a young Black man, is often a story of survival masked as success. By allowing the fear, the anger, and the trauma to breathe without the safety net of a punchline, the series creates something rare in the landscape of modern reboots: a show that feels not like a product of nostalgia, but a necessary correction. It reminds us that the Fresh Prince’s throne was never just given—it was a sanctuary from a storm that never really stopped raging.