✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Desire

It is a testament to the subversive genius of *Mad Men* that a show explicitly about the manufacturing of desire—the buying and selling of happiness—ultimately reveals that happiness to be a defective product. Matthew Weiner’s magnum opus, which ostensibly chronicles the golden age of advertising on Madison Avenue, is not really a period piece. It is a ghost story. It haunts the corridors of the 1960s not to wallow in the kitsch of mid-century furniture or three-martini lunches, but to conduct a forensic autopsy on the American Dream.

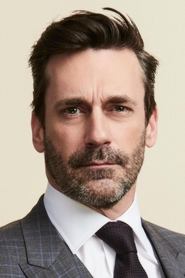

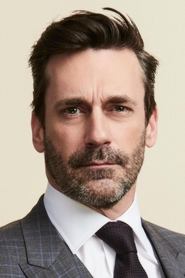

At the center of this autopsy is Don Draper, played with a stoic, crumbling majesty by Jon Hamm. Draper is not a man; he is a suit of armor occupied by a terrified fugitive named Dick Whitman. The brilliance of the series lies in this central metaphor: the greatest ad man in New York is himself a fraudulent campaign, a brand built on a lie. When Don delivers his now-legendary pitch for the Kodak Carousel in the Season 1 finale, describing nostalgia as "the pain from an old wound," he is not selling a slide projector. He is selling the one thing he can never truly possess: a past that doesn't hurt.

Visually, the series is a masterclass in claustrophobia. The cinematography eschews the shaky-cam dynamism of its contemporaries for a locked-down, voyeuristic stillness. We are often placed low, looking up at ceilings that seem to press down on the characters, trapping them in their impeccable offices. The omnipresent cigarette smoke does not just provide texture; it acts as a literal screen, a haze through which these characters view a world that is rapidly leaving them behind. Weiner’s obsession with historical accuracy—the right lamps, the right labels—serves a narrative function: the sets are so perfect they feel suffocating, emphasizing the messy, chaotic emotional lives bleeding out onto the pristine carpets.

While the series is anchored by Don, its moral gyroscope is Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss). If Don represents the dying archetype of the self-made man who reinvents himself through deceit, Peggy represents the painful, authentic birth of the modern woman. Their relationship is the show’s beating heart, culminating in the masterpiece episode "The Suitcase." In that hour, stripped of the glamour and the entourage, we see them as they truly are: two lonely workaholics who understand that in a world of transactions, their shared trauma is the only currency that holds value.

The series finale, often debated, offers perhaps the most cynical yet honest conclusion in television history. Don, having stripped away his possessions and confessed his sins at a spiritual retreat, seemingly achieves enlightenment—only to immediately metabolize that peace into a Coca-Cola jingle. It is a chilling realization: the system always wins. Don Draper does not find redemption; he finds a better tagline.

*Mad Men* remains a towering achievement not because it glamorized the past, but because it exposed the timelessness of our discontent. It suggests that we are all, in some way, waiting for a pitch that will explain who we are, unaware that we are the ones writing the copy.