The Silence of the DinéIn the vast, sun-bleached expanse of the American Southwest, silence is not merely the absence of sound; it is a heavy, living entity. It holds the history of a people, the secrets of the land, and the unspoken traumas of men who are forced to walk the line between two worlds. *Dark Winds*, the AMC noir thriller adapted from Tony Hillerman’s celebrated novels, understands this silence. It does not try to fill the void with the frantic noise typical of modern police procedurals. Instead, it lets the silence linger, creating a suffocating atmosphere where the ghosts of the past are just as dangerous as the flesh-and-blood killers roaming the Navajo Nation.

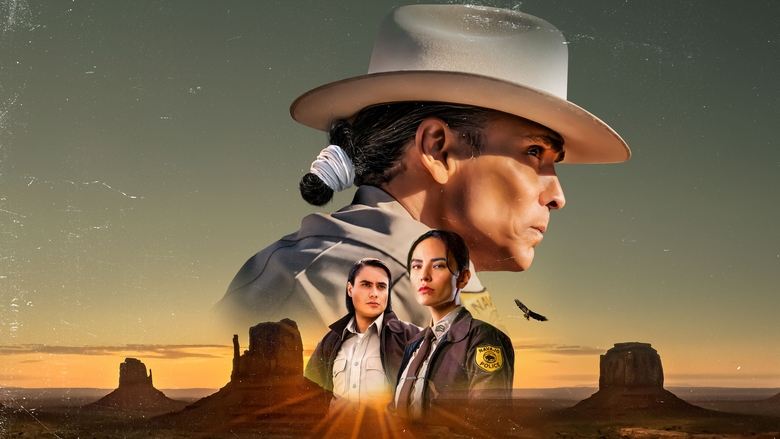

To call *Dark Winds* a "crime show" is to do it a disservice. It is, at its heart, a study of identity under siege. Set in the 1970s, a decade of radical shifts and lingering wounds, the series follows Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn (the magnificent Zahn McClarnon) and his new deputy Jim Chee (Kiowa Gordon). On the surface, they are solving a double murder and a bank robbery. But beneath the procedural mechanics lies a far more compelling conflict: the struggle to maintain spiritual equilibrium in a world designed to disrupt it.

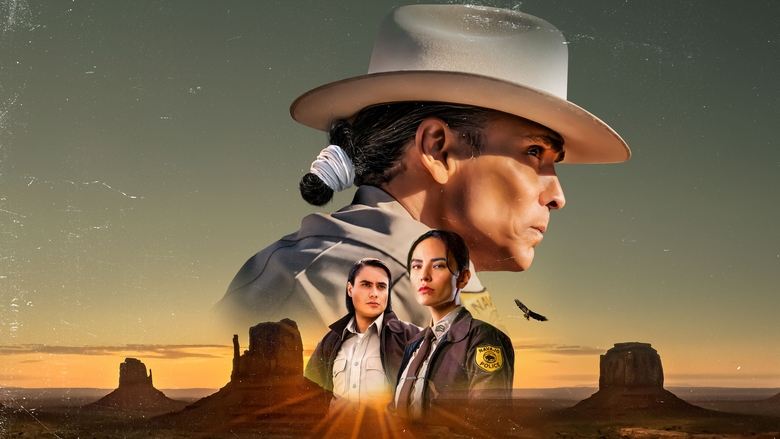

The visual language of the series is striking. The directors treat the Monument Valley not as a scenic backdrop, but as a cathedral—ancient, indifferent, and sacred. The cinematography captures the relentless heat and the overwhelming scale of the landscape, shrinking the human characters to specks of dust. This visual isolation mirrors Leaphorn’s internal state. He is a man who carries the weight of "Indian justice" and the rigid expectations of federal law, often finding that neither offers true solace. The use of the 1970s setting is not merely aesthetic nostalgia; it places the characters in a specific moment of political tension, where the wounds of colonization are fresh and the skepticism toward institutions—both white and tribal—is palpable.

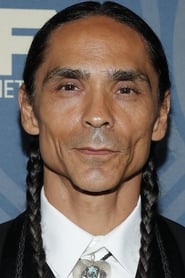

The series' greatest triumph, however, is Zahn McClarnon. For years a standout character actor in shows like *Fargo* and *Westworld*, McClarnon here delivers a performance of profound stillness. His Leaphorn is a man of few words, but his face—etched with grief and stoic resolve—speaks volumes. Watch the way he moves through a crime scene: there is no sensationalism, only a weary reverence for the dead. The chemistry between him and Gordon’s Chee—a younger, more assimilated officer returning to the reservation—provides the show’s dialectic friction. They represent two generations of Indigenous experience: one rooted in the old ways but pragmatic about survival, the other drifting, looking for an anchor.

While the narrative occasionally stumbles over the complex web of its own mystery—tangling itself in FBI conspiracies that feel less urgent than the tribal politics—it recovers whenever it returns to the domestic and the spiritual. The inclusion of Navajo mysticism is handled with a delicate touch; it is neither exoticized for "spooky" effect nor explained away by Western logic. It simply *is*, a reality of life for these characters that demands respect.

*Dark Winds* is a significant step forward in the decolonization of the Western genre. It reclaims the narrative space of the Southwest, populating it with characters who are not tragic victims or mystical tropes, but complex, flawed human beings trying to find order in chaos. It suggests that justice is not always about the law; sometimes, it is about restoring harmony to a world that has been thrown out of balance. In the quiet dignity of Joe Leaphorn, we see a hero not defined by his badge, but by his endurance.