✦ AI-generated review

The Mirror’s Darker Reflection

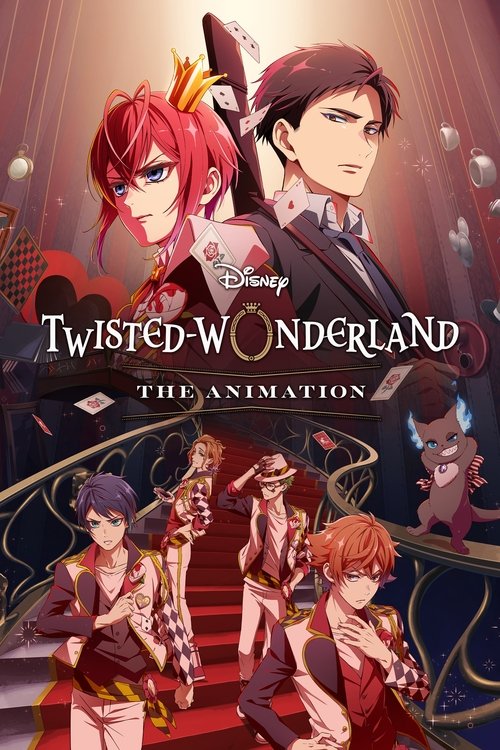

For decades, the Disney Villain was a figure of simple, delicious malice. Maleficent didn’t need a reason to curse a baby; Scar didn’t require a tragic backstory to usurp a throne. They were functional evils, designed to be defeated. But modern culture has shifted its gaze from the hero’s journey to the villain’s trauma, and nowhere is this shift more stylistically aggressive than in *Disney Twisted-Wonderland: The Animation*. Arriving on screens in late 2025, this adaptation of the phenomenon mobile game does more than simply repackage nostalgia; it transmutes the "Disney Adult" psyche into a gothic, high-stakes melodrama about the suffocating weight of expectations.

Directed by the team at Yumeta Company and Graphinica, with character designs by *Black Butler* creator Yana Toboso, the series is visually intoxicated with its own premise. The animation does not merely move; it poses. Night Raven College, the setting for our displaced protagonist Yuu, is rendered not as a school, but as a cathedral to the darker impulses of magic. The architecture is sharp, the shadows are deep, and the color palette is purposefully bruised—rich purples, crimsons, and blacks that suggest a world in a constant state of twilight.

The brilliance of *Twisted-Wonderland* lies in how it weaponizes the aesthetic of "camp" to explore genuine psychological distress. Nowhere is this more evident than in the "Episode of Heartslabyul," the arc dominating the first season. Here, the text reimagines the Queen of Hearts not as a tyrannical matron, but as Riddle Rosehearts, a diminutive, high-strung authoritarian whose obsession with rules is revealed to be a desperate defense mechanism.

In the pivotal "Unbirthday Party" scene, the animation shifts from whimsical to suffocating. As Riddle loses control, the visual motif of the "Overblot"—a magical corruption where ink drips like black tar—becomes a terrifying metaphor for emotional repression. We are not watching a villain being evil; we are watching a child breaking under the demand for perfection. The camera lingers on the collar Riddle wears—a symbol of control he imposes on others, but which the narrative astute reveals is actually choking *him*. The directing choices here transform a scene of magical combat into a frantic intervention, stripping away the "isekai" fantasy tropes to reveal a raw, human panic.

It would be easy to dismiss the series as a parade of "ikemen" (handsome men) designed solely for aesthetic consumption. Yet, the writing, spearheaded by Yoichi Kato, treats these archetypes with surprising tenderness. The "villains" are not evil; they are the result of virtues taken to toxic extremes. Diligence becomes tyranny; ambition becomes predation. Yuu, the magic-less protagonist, serves less as a hero and more as a mirror, reflecting these distorted virtues back at the students until they crack.

*Disney Twisted-Wonderland: The Animation* is not a deconstruction of Disney, but a maturation of it. It argues that the monsters under the bed are often just people who were never allowed to fail. In an era of cinema obsessed with redeeming the irredeemable, this series succeeds by suggesting that the true villain isn't the boy on the throne, but the rigid systems that put him there. It is a work of jagged beauty—flawed, excessive, and utterly captivating.