✦ AI-generated review

The Long Funeral of Civilization

When *The Walking Dead* premiered in 2010, it arrived not merely as a television show, but as a silent scream. In an era before the monoculture fractured, it managed to turn the grotesque into the communal. Yet, to view it simply as a "zombie show" is to misunderstand its initial ambition. At its genesis, developed by Frank Darabont, this was a neo-Western dressed in rotting flesh—a meditation on what happens when the social contract is not just broken, but eaten alive.

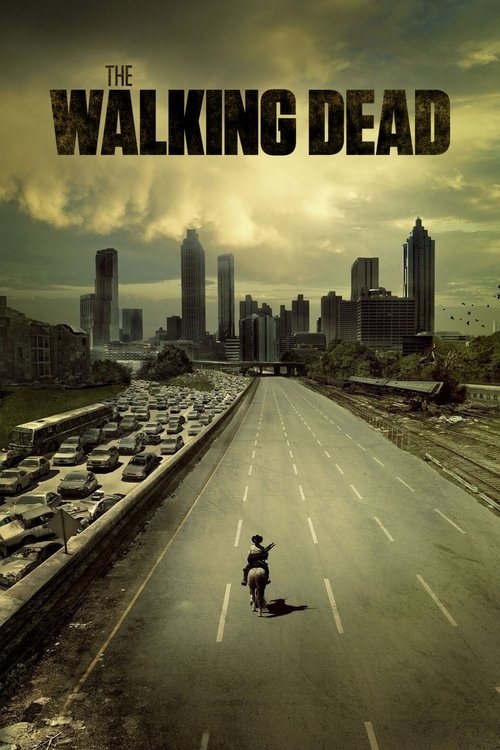

The pilot episode, "Days Gone Bye," remains a masterclass in visual storytelling. Darabont, bringing a cinematic grandeur usually reserved for the silver screen, painted the apocalypse with wide, terrifying brushstrokes. Consider the iconic image of Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) riding a horse into a desolate Atlanta. The scene is not defined by action, but by a suffocating, sun-bleached silence. The vast emptiness of the highway, juxtaposed with the crowded misery of the city, established a visual language of isolation that the series would ride for over a decade. In these early moments, the horror was atmospheric; the dread came from the landscape itself, which had become a tomb for the modern world.

However, as the series expanded into its staggering eleven-season run, the visual language shifted. The widescreen vistas of the early days slowly contracted into the claustrophobic, gray woods of Georgia and Virginia. This aesthetic constriction mirrored the narrative’s descent. The show transformed from a survivalist odyssey into a grim anthropological experiment. The central question shifted from "How do we survive the dead?" to "What do we owe the living?" It is a potent philosophical inquiry, but one that the series occasionally bludgeoned with a lack of subtlety.

The discourse surrounding *The Walking Dead* often centers on its brutality, specifically the introduction of the antagonist Negan in Season 7. This moment serves as a critical fissure in the show’s legacy. The infamous "lineup" scene, where beloved characters were executed with performative cruelty, marked a transition from tragedy to nihilism. Where earlier deaths felt like the inevitable cost of a dying world, this felt like punishment for the audience's loyalty. It was here that the show arguably betrayed its humanistic roots, trading the melancholy of loss for the shock of the abattoir.

Yet, despite its narrative stumbles and cyclical pacing—finding a sanctuary, losing it, walking on—the series maintained a beating heart in its performances. Andrew Lincoln’s Rick Grimes was never a generic action hero; he was a man slowly eroding. We watched his eyes harden, his morality calcify, and his very humanity stripped away layer by layer until the title of the show revealed its true double entendre: the "walking dead" were never the zombies. They were the survivors, hollowed out by trauma, shuffling through a world that no longer had a place for them.

Ultimately, *The Walking Dead* stands as a monumental, if imperfect, pillar of modern television. It brought the horror genre out of the niche shadows and into the prestigious Sunday night slot, proving that audiences were hungry for a confrontation with their own fragility. It was a long, exhausting, and often beautiful funeral procession for civilization—a reminder that in the end, the scariest thing in the dark isn't the monster, but the person standing next to you.