✦ AI-generated review

The Monster in the Morning Light

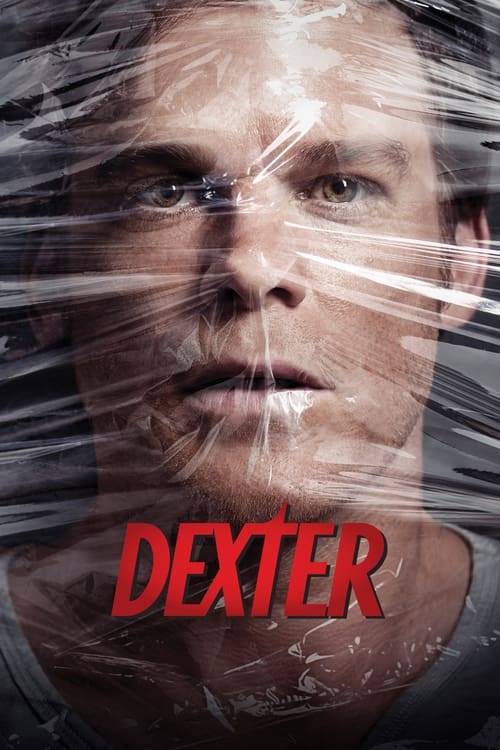

In 2006, television was in the throes of a moral revolution. We were already fascinated by Tony Soprano’s panic attacks and Al Swearengen’s brutal pragmatism, but *Dexter* dared to push the anti-hero archetype into the realm of the impossible. While his contemporaries were bad men doing bad things for power or family, Dexter Morgan was something far more unnerving: a monster pretending to be a man, doing bad things for the "greater good." Looking back at the original series, it remains a singular study in cognitive dissonance—a show that seduced us into rooting for a serial killer not by hiding his nature, but by exposing his desperate, terrifying attempt to construct a human soul.

The genius of *Dexter* lies in its visual language, which rejects the rainy, shadow-drenched clichés of film noir. Instead, the series gave us "Miami Noir"—a suffocatingly bright aesthetic where the Florida sun bleaches everything but the blood. The cinematography is drenched in saturated primary colors: the neon turquoise of the ocean, the violent pinks of Art Deco hotels, and, inevitably, the deep crimson of life spilling out. This juxtaposition is established immediately in the show’s opening title sequence, a masterpiece of visual storytelling. As Dexter performs his morning routine—shaving, slicing a blood orange, flossing—the extreme close-ups and aggressive sound design render these mundane domestic acts as violent as murder. Before a word is spoken, the show tells us that for Dexter, existing in the human world is a brutal performance.

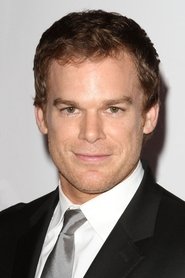

At the center of this sunlit nightmare is Michael C. Hall, whose performance is a high-wire act of restraint. Hall plays two characters simultaneously: the "mask," a goofy, donut-bringing lab geek, and the "Dark Passenger," the hollow entity that narrates the show. The voiceover, a device often considered a crutch in lesser scripts, is essential here. It creates an intimate complicity with the audience. We are the only ones who know the truth; we become his confidants in a way his sister Deb or his girlfriend Rita never can be. Hall’s brilliance is in the micro-expressions—the vacant stare that snaps into a practiced smile when a colleague walks by. He makes us feel the exhaustion of his camouflage.

The show’s central tension isn't "Will he get caught?", but "Can a monster learn to love?" The tragedy of *Dexter* is that the "Code of Harry"—the set of rules designed to channel his urges toward killing other killers—evolves from a survival mechanism into a moral cage. As the seasons progress, Dexter’s mask begins to graft onto his face. He starts to care for Rita and her children, not just as cover, but as genuine anchors. This is where the show finds its emotional weight: the realization that Dexter is most dangerous not when he is killing, but when he tries to be human. His attempts at connection invariably destroy the people he seeks to protect, turning the series into a slow-motion Greek tragedy.

It is impossible to discuss *Dexter* without acknowledging that its narrative ambition eventually outpaced its execution. The later seasons, particularly the original 2013 finale, are widely regarded as a collapse, where the show’s tight internal logic unraveled into melodrama. Yet, the cultural footprint of those early years is indelible. By forcing us to empathize with a butcher, *Dexter* interrogated the darkness inside the viewer. It asked us why we enjoy the violence, and in the bright, blinding light of Miami, it offered no easy answers—only a blood slide, a trophy of the sins we watched and secretly enjoyed.