✦ AI-generated review

The One Where We Never Left

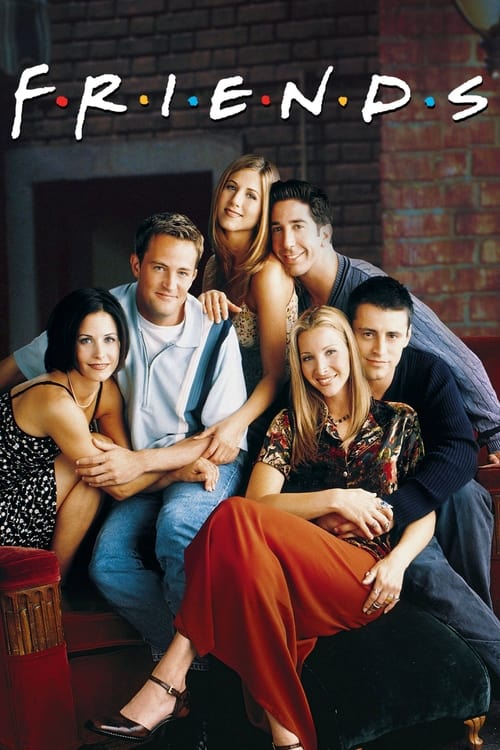

If you look closely at the pilot of *Friends*, aired in the autumn of 1994, you are witnessing something more than the birth of a sitcom juggernaut; you are watching the last gasp of a specific kind of American optimism. Before the digital fragmentation of the 21st century, there was the "hangout"—a physical space where presence was mandatory and silence was impossible. Creators David Crane and Marta Kauffman didn’t just build a show about six New Yorkers; they constructed a terrarium of suspended adolescence, a gilded cage with purple walls where the terrifying variables of the real world—economic collapse, political polarization, the crushing solitude of the internet age—were barred from entry.

Visually, *Friends* operates on a frequency of aggressive comfort. The multi-camera format, often derided by modern cinematic purists as flat or stagelike, here serves a vital ritualistic function. The lighting is uniformly warm, banishing shadows from the corners of Central Perk. The geography of Monica’s apartment is less a floor plan and more a psychological safe harbor; the open kitchen and the oversized window frame a stage where tragedy is only ever a setup for a punchline. Even the laugh track, a relic of television past, functions not as a cue for when to laugh, but as a communal heartbeat, assuring the viewer that they are part of a collective, that they are not watching alone.

However, to view *Friends* solely as "comfort content" is to miss the melancholy undercurrent that has only deepened with time. The heart of this show is not the operatic, on-again-off-again romance of Ross and Rachel, which often collapses into toxic possessiveness. The true emotional anchor is Chandler Bing. Through the lens of history, and the tragic passing of Matthew Perry, Chandler’s sarcasm transforms from a comedic device into a desperate shield. Perry played Bing not just as a joker, but as a man terrified of his own interiority. His frantic energy, his need to fill every silence with a quip, speaks to a thoroughly modern anxiety. When he finally finds stillness with Monica, it isn't just a plot point; it is the show’s most profound act of healing.

Critics often point to the show's dated politics—the lack of diversity, the casual homophobia, the fat-shaming—and these critiques are valid. The world of *Friends* is undeniably sanitized, a fantasy of Manhattan where a waitress can afford a sprawling West Village apartment. Yet, the show endures not because it reflects reality, but because it fulfills a primal deficit in modern life. It posits a world where your friends are your family, where the door is always unlocked, and where the most pressing crisis can be solved with a conversation on a velvet couch.

Ultimately, *Friends* is a monument to the interim—that fleeting, magical, and terrifying decade of your twenties when the future is a concept and the present is everything. We return to it not to see how the story ends, but to linger in the perpetual middle, where the coffee is hot, the rent is paid, and the people we love are just across the hall.