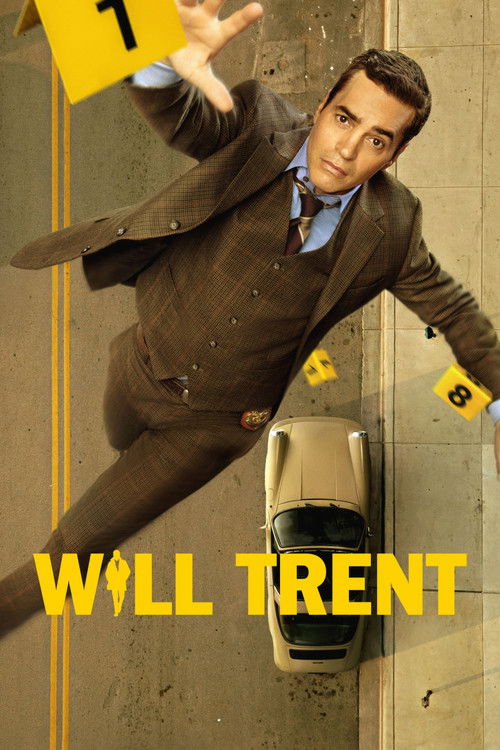

The Architecture of ScarsThe modern police procedural often suffers from a mechanical coldness. We are usually presented with a brilliant, socially abrasive detective who treats crime scenes like algebra equations—problems to be solved, variables to be isolated. But *Will Trent*, adapted from Karin Slaughter’s bestselling novels, dares to suggest that the investigator is not merely solving the puzzle, but is himself a scattered collection of jagged pieces trying to find a cohesive shape. It is a show less interested in the "whodunit" than in the "how do we survive it?"

The visual language of the series, particularly its depiction of the protagonist's dyslexia, offers a refreshing break from the genre’s reliance on sterile forensic labs. When Special Agent Will Trent (played with a soulful, bruised quietness by Ramón Rodríguez) looks at a document, the letters don't just blur; they dance and scramble, visualizing a chaotic world that he must constantly decode. This is not treated merely as a disability to be "overcome" for the sake of the plot, but as the foundation of his worldview. Because he cannot rely on the literal text, he reads the subtext—the shift in a suspect’s posture, the missing shoe at a crime scene, the silence in a room. The camera mimics this subjective reality, often isolating Will in the frame, emphasizing his profound loneliness even in a crowded bureau.

In this adaptation, the harsh, gritty violence of Slaughter’s novels is tempered by a surprising warmth, largely carried by Rodríguez’s performance. In the books, Will is a tall, blonde, imposing figure; the series reinterprets him as a compact, meticulous Latino man who wears three-piece suits as a form of medieval armor. The suit is a crucial visual metaphor: it is the wall he builds between his traumatic past in the Atlanta foster care system and the "respectable" world of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. He buttons himself up to keep the chaos out.

The heart of the series lies in its refusal to sanitize the lingering effects of childhood trauma. While many procedurals use a tragic backstory as flavor text, *Will Trent* allows the wounds to breathe. The relationship between Will and Angie Polaski (Erika Christensen), a fellow survivor of the foster system, is depicted with a messy, uncomfortable honesty. They are two people who know each other's ghosts, bound by a shared history that is both a comfort and a curse. The show does not shy away from the idea that survival has a cost—that the coping mechanisms that kept you alive as a child might drown you as an adult.

Yet, the series avoids becoming an exercise in misery through its unexpected flashes of humanity—most notably in the form of Betty, the chihuahua Will reluctantly adopts. It is a classic trope (the tough guy and the tiny dog), but it serves a vital narrative function: it forces Will, a man who has learned that attachment leads to abandonment, to care for something vulnerable.

*Will Trent* succeeds because it understands that justice is not just about catching the killer; it is about witnessing the pain of the victim. In a television landscape crowded with cynical anti-heroes, Will Trent stands apart as a character driven not by ego, but by a desperate, deeply personal need to prevent others from feeling the abandonment he knows too well. It is a procedural with a pulse, hiding a tender, beating heart beneath its tailored vest.