The Architecture of SinIn the landscape of modern Chinese crime noir—specifically the *sahei* (sweeping away darkness) genre—there is a tendency for narratives to drift into the didactic. The lines are often drawn with heavy chalk: the righteous police officer on one side, the chaotic gangster on the other. However, *Chasing the Undercurrent* (2022), directed by Tian Yi, manages to disturb this binary by introducing a gravitational pull that is less about the law and more about legacy. While it wears the uniform of a police procedural, at its heart, this is a dynastic tragedy, a story of a crumbling empire that feels closer to *The Brothers Karamazov* than a standard primetime investigation.

The series is set in the fictional Changwu City, a metropolis suffocated by the grip of the Zhao family. What distinguishes this narrative is not the "whodunit"—we know the Zhao family is guilty from the opening frames—but the "how." The series posits that the most dangerous form of corruption is not the thug wielding a bat, but the architect wielding a fountain pen. The director uses the city itself as a character; the skyline is often filmed in oppressive grays and rain-slicked neons, suggesting a world where the moral compass is spinning wildly due to magnetic interference from the Zhao estate.

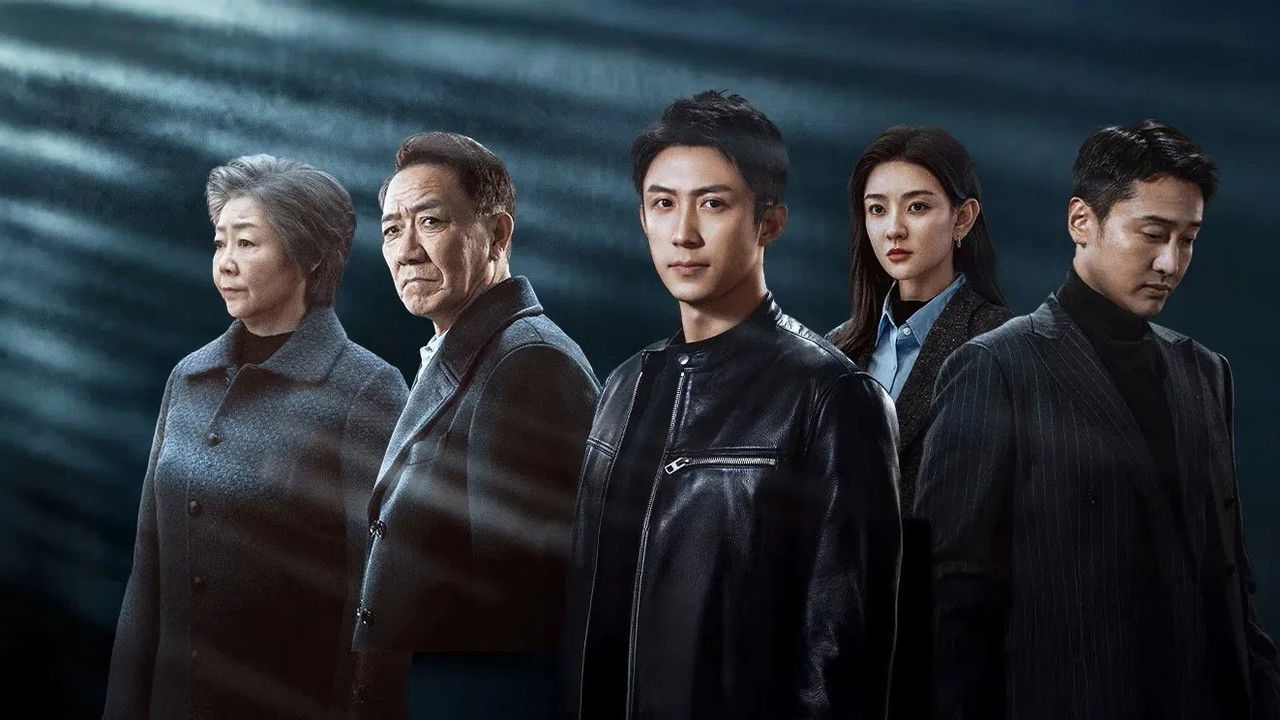

The visual language of the film serves the central conflict between the visceral and the cerebral. Johnny Huang plays Chang Zheng, the vice captain of the criminal police brigade, with a frantic, physical energy. He is the battering ram—emotional, reactive, and perpetually bruised. But the series finds its true center of gravity in his antagonist, Zhao Pengchao (played with chilling restraint by Tony Yang). As the fourth son returning from Australia, Pengchao represents a terrifying evolution of crime: he is gentle, educated, and meticulously organized. He doesn't want to burn the city; he wants to own the ashes.

The scenes between the Zhao brothers are where the script truly flexes its muscles. We watch the friction between the old-school, violent criminality of the elder brothers and the modernized, corporate sociopathy of Pengchao. This is not just a fight for territory; it is a fight for the soul of the underworld. The "undercurrent" of the title refers not just to the hidden crimes, but to the subterranean emotional ties that bind Chang Zheng to this family in ways he—and the audience—do not initially understand. The investigation becomes a mirror, and every layer Chang Zheng peels back reveals a reflection he despises.

While the series eventually bows to the genre's requisite moral clarity—Chang Zheng must choose justice over "affection" and kinship—the journey there is surprisingly textured. The narrative does not shy away from the idea that the law is fragile when faced with a family tree that has roots in every institution. The tension creates a suffocating reality where trust is a liability.

Ultimately, *Chasing the Undercurrent* succeeds because it allows its villain to be the most compelling person in the room. It acknowledges that evil is not always ugly; sometimes it is well-dressed, soft-spoken, and incredibly patient. By the time the final act arrives, the viewer is left with the unsettling realization that while the police may capture the criminals, the architecture of sin they built is far harder to dismantle.