✦ AI-generated review

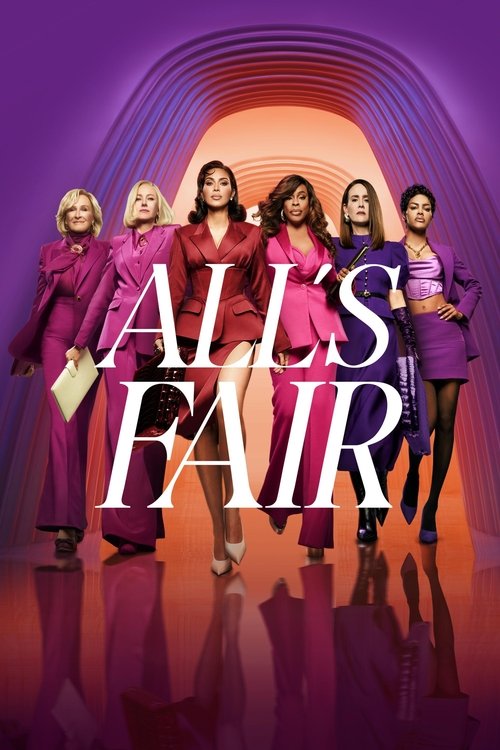

The Gilded Void

There was a time when Ryan Murphy functioned as American television’s court jester of excess. In works like *Nip/Tuck* or *The People v. O. J. Simpson*, he operated with a surgical understanding of the grotesque, dissecting our national obsessions with fame, beauty, and crime. But with *All’s Fair*, released on Hulu this month, the scalpel has been replaced by a smoothing filter. This legal drama, which centers on an all-female divorce firm in Los Angeles, does not satirize the vacuous nature of modern celebrity—it capitulates to it. We are no longer watching a critique of the culture; we are watching the culture eat itself alive.

From the opening frames, the visual language of *All’s Fair* establishes a suffocating perfection. The cinematography shares less in common with cinema than it does with high-end real estate listings or a Skims campaign. Every surface is marble, every skyline is golden-hour infinite, and every face is virtually poreless. It is a visual landscape that rejects texture. This sterility is not an artistic choice to highlight the coldness of divorce law; it is the default setting of a production that prioritizes "assets"—both human and inanimate—over narrative breath. The result is a viewing experience that feels less like watching a story unfold and more like scrolling through a curated Instagram feed that refuses to refresh.

At the center of this expensive void is Kim Kardashian as Allura Grant. To critique her performance as "wooden" is to miss the point of her presence. Kardashian is not tasked with playing a character; she is tasked with projecting a Brand. She moves through the scenes with the careful, restricted motion of someone wearing a garment they cannot sit down in. When placed against the feral, nervous energy of Sarah Paulson (playing rival attorney Carrington Lane) or the steely gravitas of Glenn Close (as the firm’s matriarch, Dina Standish), the disconnect is jarring. It creates a metaphysical crisis on screen: we are watching actors trying to construct a reality colliding with a reality star who thrives on artificiality.

This friction comes to a head in the widely discussed "Halloween" sequence, where Paulson’s character arrives dressed as a "whore lawyer," a meta-jab at Allura’s (and implicitly Kardashian’s) hyper-sexualized professional image. It is a scene that strives for the biting wit of *Succession* but lands with the thud of a Twitter feud. The dialogue, intended to be camp, lacks the requisite joy or subversion. Instead, it feels mean-spirited and transactional, a series of "clapbacks" written by an algorithm designed to generate TikTok clips rather than dramatic tension.

Perhaps the most dispiriting aspect of *All’s Fair* is its politics. The series markets itself under the banner of empowerment—"women representing women"—yet its version of feminism is strictly mercenary. The "sisterhood" promised in the synopsis is maintained only through the accumulation of wealth and the destruction of ex-husbands. There is no solidarity here, only shifting alliances of convenience. When Naomi Watts’s character, Liberty Ronson, speaks of "changing the game," she seems to refer only to the billable hours.

Ultimately, *All’s Fair* represents the heat death of "Camp." True camp requires a degree of failure, a gap between ambition and execution, or a sincere love for the unnatural. This series is too calculated, too expensive, and too self-aware to be camp. It is engagement bait dressed in couture. It creates a vacuum where emotional truth should be, daring us to look away. And in 2025, the tragedy is not that the show is empty, but that we are too mesmerized by the shine to stop watching.