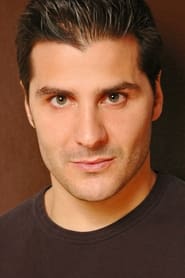

The Weight of SilenceThere is a particular kind of exhaustion that Luis Tosar wears like a second skin. It is not merely the fatigue of the characters he plays, but a deep, geological sedimentation of Spanish history and masculine failure. In "Salvador," the new Netflix limited series from creator Aitor Gabilondo ("Patria"), this exhaustion finds its most harrowing vessel yet. We are accustomed to the thriller format using extremism as a plot device—a loud, chaotic backdrop for a hero's journey. However, "Salvador" inverts this formula. It is not about the noise of the riot; it is about the deafening silence that follows the discovery that your own blood has become a stranger.

The series arrives at a moment of cultural fragility, where the discourse around radicalization often happens in the abstract. Gabilondo, paired with the kinetic direction of Daniel Calparsoro, grounds this abstraction in the visceral. The premise—an ambulance driver, Salvador Aguirre, discovering his daughter Milena is a member of a violent neo-Nazi "ultra" group—could have easily veered into "Taken"-style vengeance pornography. Instead, the show demands we look at the logistics of hate. The camera does not glamorize the violence of the "White Souls"; it treats their brutal confrontations with a clinical, almost nauseating detachment. The visuals are grey, concrete, and suffocating, mirroring Salvador’s internal landscape as a recovering alcoholic who realizes his sobriety cannot fix the past.

Calparsoro’s direction shines brightest in the pilot's inciting incident: a clash between rival football ultras. The sequence is a masterclass in confusion. We are denied the clarity of "good guys vs. bad guys." Instead, we are trapped in Salvador’s ambulance, viewing the carnage through windshields and flickering streetlights. When he finds Milena, not as a victim of the violence but as a perpetrator of it, the visual language shifts from chaotic handheld to a terrifying stillness. This is the show's thesis statement: the horror isn't the physical blow, but the realization of who is holding the weapon.

At its heart, "Salvador" is a tragedy about the "bewilderment" of a generation of parents. Tosar delivers a performance of monumental restraint. He plays Salvador not as a hero, but as a man disintegrating. His infiltration of the White Souls isn't driven by a tactical desire to dismantle a cell, but by a desperate, almost pathetic need to understand *why*. Why did the daughter he raised with leftist values embrace fascism? The script refuses to offer easy sociological answers about poverty or lack of opportunity. It suggests something far more uncomfortable: that hate provides a sense of belonging that broken families often fail to offer.

Ultimately, "Salvador" is a demanding watch, not because of its graphic content, but because it denies us the catharsis of a clear moral victory. By the time the eight episodes conclude, we are not cheering for justice; we are mourning the loss of a future. In a landscape of streaming television that often prioritizes momentum over meaning, "Salvador" dares to stop the ambulance, turn off the siren, and force us to look at the casualty in the back. It serves as a grim reminder that sometimes, the most dangerous radicalization happens not in the streets, but in the quiet, unaddressed voids of our own living rooms.