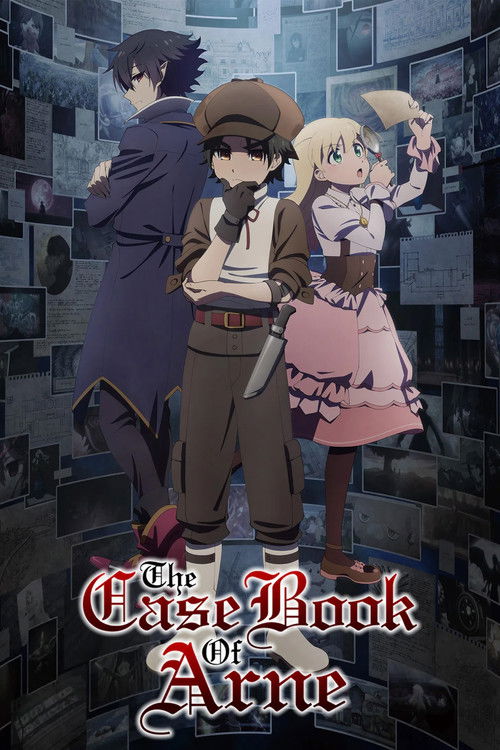

The Crimson Logic of LügenbergThere is a specific, peculiar dissonance found in Japanese media that layers the aesthetic of a children’s storybook over the gruesome mechanics of a slaughterhouse. It is a genre where frilly dresses and blood spatters do not just coexist; they compliment one another. "The Case Book of Arne," the 2026 adaptation of Harumurasaki’s indie game, operates entirely within this cognitive dissonance. Directed by Keisuke Inoue, a filmmaker previously known for the buoyant energy of *My Next Life as a Villainess*, this series trades sunshine for moonlight, delivering a gothic mystery that is as charming as it is morbid.

The premise is deceptively standard for the supernatural detective subgenre: Arne Neuntöte, a vampire "detective" with the swagger of a weary immortal, pairs up with Lynn Reinweiß, a vampire-obsessed noblewoman who treats homicide investigations like a twisted tea party. However, Inoue’s direction elevates what could have been a rote procedural. The visual language of the anime, produced by SILVER LINK, retains the "flat," almost paper-doll quality of its RPG Maker origins, but uses it to unsettle rather than comfort. When violence erupts in the city of Lügenberg—a sanctuary for non-humans—it feels jarringly real against the show's pop-gothic art direction. Inoue understands that in a world where monsters are the citizens, the mystery isn't just *who* did it, but *what* nature of hunger drove them to it.

The show’s most fascinating tension lies not in the puzzles themselves, but in the friction between its leads. Lynn is not the shrinking violet victim common to gothic romances; she is proactive to the point of recklessness, driven by a fetishistic curiosity about the macabre that mirrors the audience’s own gaze. Arne, conversely, is the reluctant participant, a monster bored by his own mythology. Their dynamic is the series' engine, and the script (supervised by the original game creator) wisely refuses to soften the edges of their relationship. They are allies by circumstance, not by moral alignment. The introduction of the anime-original character, Luis, adds a necessary third leg to this stool, disrupting the established duo dynamic and forcing the narrative to expand beyond the binary of "Human vs. Monster."

If the series stumbles, it is perhaps in its ambition to marry the logic of a video game—where players have agency and branching paths—with the linear immutability of television. There are moments where the deduction feels rushed, where the "evidence" is presented to the viewer with the speed of a dialogue box clicking shut. Yet, these are minor grievances in a show that commits so fully to its tone. "The Case Book of Arne" is not interested in the gritty realism of modern noir; it is a dark cabaret. It asks us to look at the blood on the floor and notice how nicely it contrasts with the carpet. In a season of safe sequels, this is a welcome, wicked little delight.