✦ AI-generated review

The Architect of Our Nightmares

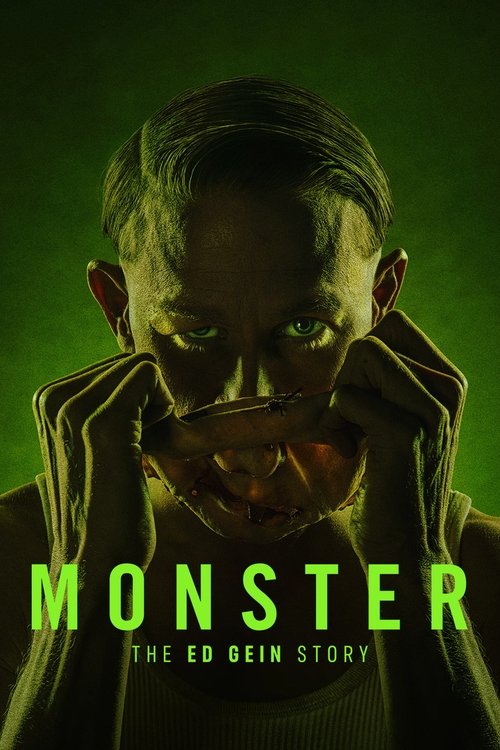

If Jeffrey Dahmer was the monster who terrified the modern city, and the Menendez brothers were the monsters who scandalized the televised courtroom, Ed Gein occupies a stranger, more primal space in the American psyche. He is the quiet, rural "Patient Zero" of our cinematic anxieties—the clay from which Alfred Hitchcock molded Norman Bates, Tobe Hooper carved Leatherface, and Thomas Harris stitched together Buffalo Bill. In *Monster: The Ed Gein Story*, creators Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan return to this genesis point, attempting to strip away the decades of Hollywood mythmaking to reveal the pathetic, suffocating reality of the man himself. The result is a work that is visually arresting and performed with unnerving commitment, yet it ultimately collapses under the weight of its own meta-textual ambition.

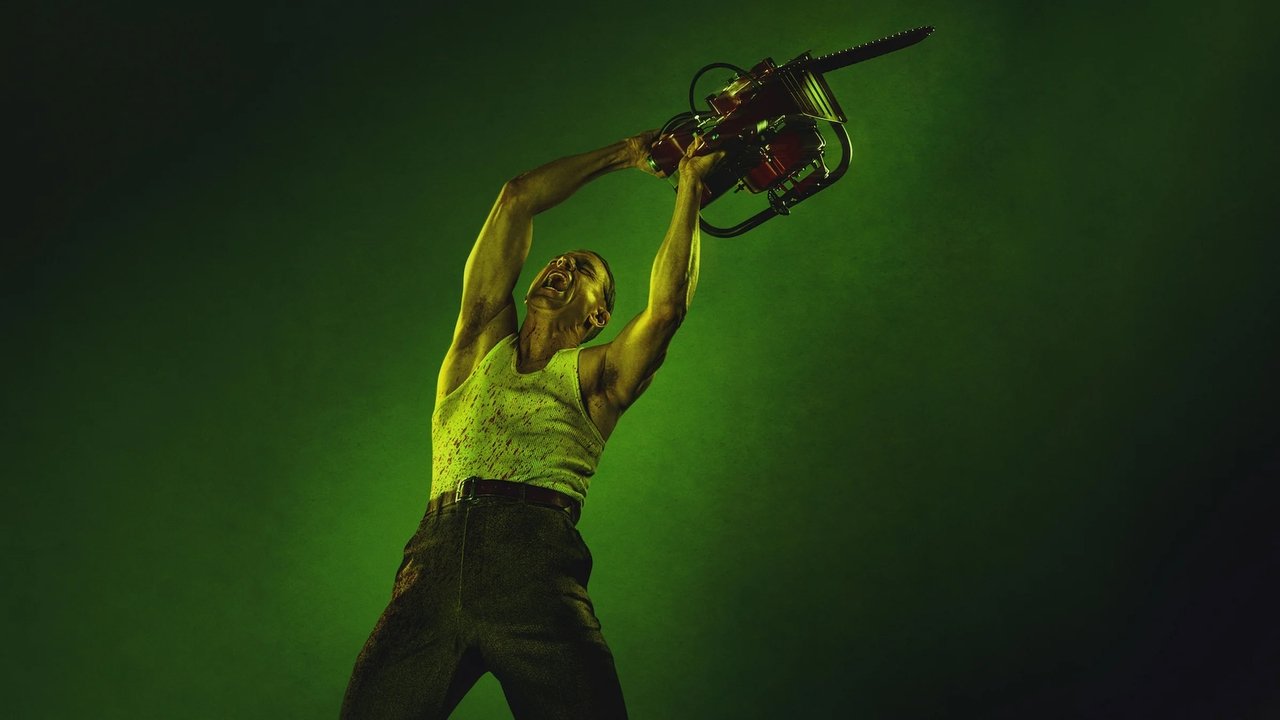

Visually, the series abandons the neon-soaked grime of its predecessors for the sepia-toned desolation of 1950s Plainfield, Wisconsin. The camera lingers on the frozen farmland and the claustrophobic interiors of the Gein farmhouse with a painterly dread. There is a tactile repulsiveness to the production design; you can almost smell the rot and the stale dust. However, the directors make a controversial choice to intersperse this grimy realism with stylized recreations of the films Gein inspired. When the series recreates the *Psycho* shower scene—replacing Janet Leigh with Suzanna Son’s character and forcing Ed into the frame—it ceases to be a biography and tries to become a media critique. It asks us to look at how we transmute tragedy into entertainment, but by restaging the violence with even more graphic intensity than Hitchcock ever dared, the show becomes the very thing it purports to analyze. It doesn't deconstruct the spectacle; it merely upgrades the resolution.

At the center of this disjointed narrative is Charlie Hunnam, who delivers a transformation so total it is nearly unrecognizable. Shedding his typical leading-man bravado, Hunnam adopts a fragile, high-pitched whisper and a physicality that suggests a man trying to shrink out of existence. His Ed Gein is not a cackling villain but a hollow vessel, a terrified child trapped in a man’s decaying orbit. He plays Gein with a terrifying softness, making the character’s descent into grave-robbing and murder feel less like an explosion of rage and more like a desperate, misguided attempt to fill a void.

That void, of course, is shaped by Augusta Gein. Laurie Metcalf is formidable as the matriarch, avoiding the screeching caricature of the "evil mother" to find a more insidious, freezing coldness. Her Augusta is a woman consumed by a religious fervor that is indistinguishable from hatred. The scenes between Metcalf and Hunnam are the show’s strongest, vibrating with a toxic intimacy that explains, without excusing, the horror that follows. We see how the monster was not born, but carefully, methodically sculptured by abuse and isolation.

Yet, despite these powerful performances, the series struggles to justify its existence. By the time we reach the later episodes, where the narrative drifts into dream sequences involving other serial killers or heavy-handed dialogues about Gein’s "legacy," the emotional thread frays. The show wants to indict the audience for their obsession with the macabre, yet it lingers lovingly on the "craftsmanship" of Gein’s skin masks and furniture. It demands we feel the tragedy of the victims, yet treats them largely as props in Gein’s psychodrama.

*Monster: The Ed Gein Story* is a technical triumph that leaves a bitter aftertaste. It succeeds in humanizing a ghoul, showing us the lonely boy behind the mask of skin, but it fails to offer a reason why we needed to peer behind that mask in the first place. It is a series that stares into the abyss of American violence, only to find that the abyss is staring back, bored and desensitized, waiting for the next sequel.