The Architecture of AtonementThe courtroom drama has long been a staple of Korean television, often serving as a hygienic theater where societal rot is exposed and then, comforting to the viewer, surgically removed by a righteous prosecutor. However, *Honour* (2026), the new ENA thriller adapted from the Swedish series *Heder*, attempts something far murkier. It suggests that the scalpel used to excise the tumor is itself infected. By centering the narrative on three female defense attorneys who run a firm dedicated to victims of sexual violence, the series initially posits a clear binary of good versus evil. Yet, as the narrative unspools, director Park Gun-ho reveals that the foundation of this "good" work is built upon a strata of silenced personal history.

Visually, *Honour* is a study in claustrophobic elegance. The cinematography favors the sleek, glass-walled interiors of the L&J (Listen and Join) law firm, shooting the leads—Lee Na-young, Jung Eun-chae, and Lee Chung-ah—through reflections and refractions. They are often framed against the sprawling, indifferent skyline of Seoul, emphasizing their isolation. The lighting is cold, stripping away the warmth usually associated with "sisterhood" narratives. In one particularly striking sequence in the premiere, the camera lingers on Yoon Ra-young (Lee Na-young) applying makeup before a press conference. The extreme close-up transforms a routine act of vanity into a donning of war paint; the silence of the scene is deafening, broken only by the sharp click of a lipstick case that sounds suspiciously like the cocking of a gun. It is a visual thesis statement: for these women, appearance is armor, and vulnerability is a death sentence.

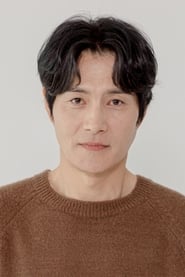

The heart of the series lies not in its procedural elements—which are competent, if occasionally reliant on genre tropes—but in the corrosive chemistry between the three leads. Lee Na-young, returning to the screen with her signature ethereal gravity, plays Ra-young not as a crusader, but as a survivor engaging in high-functioning denial. Her performance anchors the show’s central irony: these women have dedicated their lives to "listening" to victims (L&J), yet they are deaf to the screams of their own past.

The dynamic is further complicated by Jung Eun-chae’s Kang Shin-jae, whose stoicism fractures in micro-expressions when the central mystery—a twenty-year-old secret involving a cover-up—begins to surface. The series posits that their solidarity is not born of affection, but of necessity; they are bound together like mountaineers on a cliff face, where if one slips, they all fall. This is a darker, more pragmatic view of female friendship than we are used to seeing, stripped of sentimentality and replaced with the desperate adrenaline of survival.

Ultimately, *Honour* challenges the viewer to question the cost of justice. Can one truly advocate for the truth while living a lie? The show argues that the statute of limitations on trauma never really expires; it merely compounds interest. While the mystery of the "scandal" drives the plot, the real suspense is existential. We are watching three women who have built a fortress of morality to protect themselves from their own ghosts, and the fascination lies in watching the cracks begin to form in the masonry. It is a brooding, sophisticated addition to the genre that asks us to look past the gavel and the robe, into the terrified eyes of those who hold them.