Echoes from the AbyssIn the sprawling, often operatic landscape of Turkish television, the "mafia dizi" has long been a staple—a genre frequently characterized by glossy suits, slow-motion gunfights, and hyper-stylized codes of honor. Yet, with the arrival of *Underground* (*Yeraltı*), director Murat Öztürk and veteran screenwriter Bahadır Özdener seem intent on stripping away the varnish. Released in early 2026, this series does not merely recount a story of revenge; it excavates the psychological toll of a life lived in the shadows. It is a suffocating, dense, and remarkably human exploration of what happens when a man is forced to bury his humanity to survive, only to find the world above ground has moved on without him.

From the opening sequence, *Underground* establishes a visual grammar that is distinctly claustrophobic. Öztürk, steering away from the panoramic beauty of the Bosphorus that typically defines Istanbul-set dramas, forces the camera into tight, uncomfortable spaces. The prison sequences, where protagonist Haydar Ali (Deniz Can Aktaş) spends three pivotal years, are filmed with a palette of bruised blues and sickly greens. The architecture of the prison is not just a setting but a mirror to Haydar’s internal state: a labyrinth of concrete where silence is heavier than the violence. The direction creates a palpable sense of entrapment that lingers even after the character is released. The "underground" of the title is physical, yes—referencing the cartels—but it is primarily existential. The audience is made to feel the weight of the air in these rooms, a stifling pressure that suggests no one leaves this life clean.

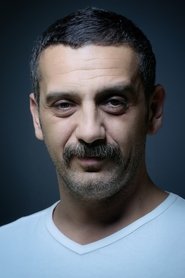

At the narrative's center is Haydar Ali, played with a simmering, restrained intensity by Deniz Can Aktaş. In previous roles, Aktaş has often leaned into the archetype of the charismatic hero. Here, he dissolves that persona. Haydar is a man hollowed out by grief. Having avenged his family’s murder only to lose his freedom, he emerges three years later not as a conquering lion, but as a ghost. The script avoids the trap of making him invincible; instead, he is dangerously fragile. The central tragedy—that Ceylan (Devrim Özkan), the woman who tethered him to sanity, is now married to his closest ally-turned-rival—is treated not as a soap opera twist, but as a Greek tragedy. The chemistry between Aktaş and Özkan is less about sparks and more about the quiet devastation of unsaid words. Their reunion scene is a masterclass in blocking and eye contact, conveying a history of pain without a single line of exposition.

What elevates *Underground* above its contemporaries is its refusal to glorify the violence it depicts. The action, when it comes, is messy, brutal, and unchoreographed. It hurts to watch. The show posits that the "underground" cartel world is not a place of power, but a purgatory for those who have nowhere else to go. By focusing on the cost of loyalty and the erosion of the self, the series transcends the mechanics of the crime thriller. It asks a difficult question: once you have descended into the dark to fight monsters, can you ever truly see the sun again? In *Underground*, the answer is a haunting, resonant silence.