✦ AI-generated review

The Burden of Miracles

In 1999, cinema was busy deconstructing reality. It was the year of *The Matrix*, *Fight Club*, and *American Beauty*—films that peeled back the skin of suburban and corporate life to reveal the rot underneath. Yet, amidst this wave of cynicism, Frank Darabont released *The Green Mile*, a three-hour, supernatural prison melodrama that felt like it belonged to a different era entirely. Adapted from Stephen King’s serialized novel, the film is an unapologetically earnest fable. It does not try to be "cool" or ironic; instead, it asks us to sit in a room with death for 189 minutes and wonder if there is any grace to be found in the machinery of state-sanctioned killing.

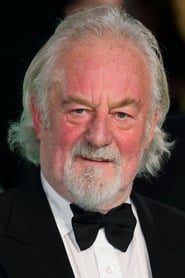

Darabont, returning to the prison genre five years after *The Shawshank Redemption*, trades the gray, industrial despair of Shawshank for the humid, suffocating atmosphere of a Louisiana death row in the 1930s. Visually, the film is bathed in a sepia-toned haze, evoking the dusty, depression-era South. The "Green Mile" itself—the lime-colored linoleum floor leading to the electric chair—is shot with a reverence usually reserved for church aisles. This is Darabont’s visual thesis: this prison block is not just a holding pen for criminals; it is a purgatory where the supernatural and the bureaucratic collide. The cinematography often isolates the characters in pools of light amidst the darkness, emphasizing the isolation of both the condemned and their executioners.

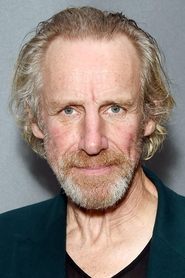

At the center of this moral play is Paul Edgecomb (Tom Hanks) and John Coffey (Michael Clarke Duncan). Hanks delivers a performance of quiet, weary decency, anchoring the film’s more fantastical elements. But the film lives and dies with Duncan. As Coffey, a towering man wrongly convicted of a horrific crime, Duncan achieves something miraculous: he plays innocence without playing stupidity. His performance is a high-wire act of physical imposition and emotional fragility. When he looks at the world, his eyes don’t just show fear; they show an exhaustion so deep it feels geological.

It is impossible to discuss *The Green Mile* without addressing the modern critique of the "Magical Negro" trope—the idea that Coffey exists solely to heal the white protagonist’s ailments and teach him a spiritual lesson. The criticism is valid; the narrative structure centers entirely on Edgecomb’s spiritual awakening, leaving Coffey as a martyr for another man's soul. However, dismissing the film on these grounds overlooks the profound tragedy Darabont and King weave into Coffey’s existence. Coffey is not a happy servant of the divine; he is a creature in agony. His gift—the ability to feel the world’s pain as his own—is depicted not as a superpower, but as an unbearable curse. "It's like pieces of glass in my head," he whispers. The film suggests that true empathy in a cruel world is not a gift, but a sentence harsher than the electric chair.

The film’s true horror lies not in its supernatural elements, but in its human ones. The character of Percy Wetmore, a sadistic guard protected by nepotism, serves as the counterweight to Coffey. Percy is the banality of evil personified—petty, cruel, and cowardly. The botched execution of the inmate Delacroix, orchestrated by Percy, remains one of the most harrowing sequences in mainstream cinema. It strips away the sanitized myth of "humane" capital punishment, forcing the audience to witness the literal burning of a human soul.

Ultimately, *The Green Mile* is a tragedy about the incompatibility of goodness and the world we have built. It argues that when the divine touches the earth, we do not worship it; we destroy it because we do not know what else to do with it. Paul Edgecomb’s "happy ending"—an unnaturally long life—is revealed to be his punishment. He must live to see everyone he loves die, a lingering ghost in a world that killed the only true miracle he ever saw. In an era obsessed with irony, *The Green Mile* remains a devastatingly sincere monument to the things we destroy in the name of justice.