✦ AI-generated review

The Body in Time

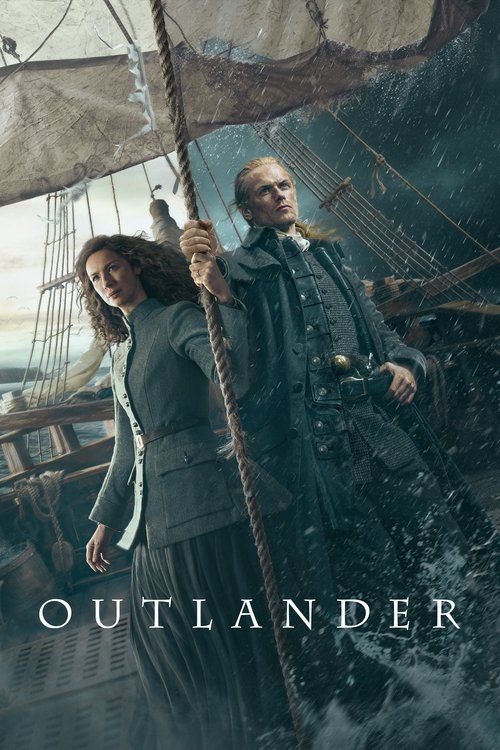

When *Outlander* premiered in 2014, developed by Ronald D. Moore (the architect of the reimagined *Battlestar Galactica*), it arrived at a cultural moment dominated by the nihilistic power struggles of *Game of Thrones*. In Westeros, love was a weakness; in the Scottish Highlands of *Outlander*, love is the only survival mechanism that works. To view this series merely as a "bodice-ripper" or a fantasy romance is to misunderstand its fundamental gravity. It is, at its core, a brutal, visceral study of the human body moving through history—how it heals, how it breaks, and how it desires.

The narrative hook—Claire Randall (Caitríona Balfe), a World War II combat nurse, touching a standing stone in 1945 and falling into 1743—is the show’s only concession to magic. Everything else is aggressively tactile. Moore and his cinematographers treat the past not as a glossy theater set, but as a place of mud, freezing rain, and infection. The visual language shifts drastically between timelines: the 1940s are rendered in sterile blues and electric lights, representing a safe but bloodless modernity, while the 18th century is bathed in candlelight, earth tones, and the deep greens of the Highlands. This contrast is not just aesthetic; it underlines Claire’s dislocation. She is a woman of science thrust into a world of superstition, and Balfe’s performance anchors this dissonance perfectly. She plays Claire not as a damsel, but as a modern pragmatist constantly frustrated by the inefficiency of the past.

Much has been made of the "female gaze" in *Outlander*, particularly regarding the framing of Jamie Fraser (Sam Heughan). It is true that the camera lingers on Heughan with a reverence usually reserved for female ingénues, subverting the traditional gender dynamics of prestige TV. However, this gaze serves a narrative purpose beyond titillation. In the famous "Wedding" episode of Season 1, the intimacy is slow, awkward, and conversational. It establishes sex not as a conquest, but as a dialogue—a sharp contrast to the sexual violence that pervades the rest of the series.

Indeed, the show’s reliance on sexual trauma as a plot device remains its most controversial and difficult element. The specter of Captain Black Jack Randall (Tobias Menzies, delivering a villain performance of terrifying, reptilian coldness) introduces a sadistic darkness that threatens to overwhelm the narrative. The Season 1 finale, which depicts the torture of Jamie, pushes the viewer’s endurance to the breaking point. Yet, the show distinguishes itself by focusing on the *aftermath* of trauma. Unlike many of its contemporaries, *Outlander* does not reset the status quo in the next episode. The scars—both physical and psychological—remain on the characters for seasons, dictating their behavior and their inability to be whole again.

Ultimately, *Outlander* succeeds because it takes the "romance" genre seriously as a vehicle for historical tragedy. It argues that history is not just a list of battles and dates, but a collection of intimate lives violently disrupted by forces beyond their control. As the series has expanded from the Highlands to the courts of France and the colonies of America (spanning seven seasons thus far), it has maintained a singular, melancholy thesis: that time is a thief, and the only rebellion we have against it is to remember.