✦ AI-generated review

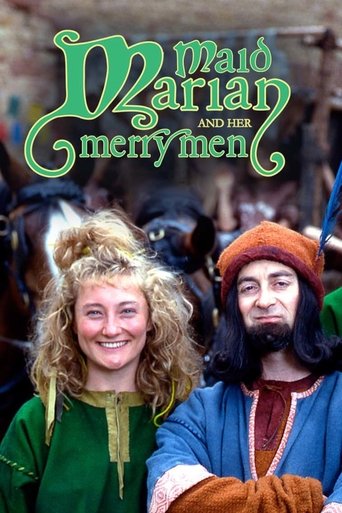

The Nostalgia for a Broken Tomorrow

In the landscape of adult animation, *Futurama* has always been an anomaly. While its sibling, *The Simpsons*, deconstructed the American nuclear family, and *South Park* weaponized shock value, Matt Groening and David X. Cohen’s sci-fi odyssey did something far more subversive: it suggested that the future would be just as disappointing, bureaucratic, and messy as the present—and that we would survive it anyway. It is a show that masquerades as a farce about robots and aliens but operates, deeply and secretly, as a meditation on loneliness and the enduring ache of the past.

Visually, the series is a triumph of "retro-futurism"—a deliberate collision of the 1939 World's Fair optimism with the grime of a 1970s tenement. The animation style, particularly the pioneering blend of 2D characters against 3D, cel-shaded ships, creates a world that feels vast yet lived-in. New New York is not a utopia; it is a sprawling, vertical favela of suicide booths and owl-infested alleyways. The genius of the show’s aesthetic is its shiny, curved surfaces that promise a *Jetsons*-like ease, constantly undercut by the reality that the technology is usually broken, lethal, or running on a subscription model you can't cancel. The visual language tells us that no matter how advanced we become, human nature—lazy, greedy, and inexplicably hopeful—remains the constant variable.

At the center of this chaos is Philip J. Fry, a character who could have easily been a one-note slacker joke. Instead, the writers treat Fry’s displacement in time as a genuine tragedy masked by incompetence. He is a refugee from history, a man who lost everyone he ever loved in the blink of a cryogenic eye. This is where *Futurama* transcends its genre. It understands that the funniest people are often the saddest.

Nowhere is this more devastatingly apparent than in the episode "Jurassic Bark." In a medium often terrified of silence, the closing sequence—a montage of Fry’s dog, Seymour, waiting faithfully through the seasons for a master who will never return—is an act of narrative bravery. There are no jokes to break the tension, no sudden reversals. It is a stark, heartbreaking look at the loyalty we leave behind. By refusing to give the audience a happy ending (at least, not until much later narrative retcons), the show declared that its emotional stakes were real. It proved that a cartoon featuring a robotic alcoholic could deliver a profound thesis on grief.

The series' own history mirrors the scrappy resilience of its characters. Having been cancelled and revived multiple times—moving from Fox to Comedy Central to Hulu—*Futurama* has become a survivor, much like the Planet Express crew itself. It endures not because of its high-concept sci-fi rigmarole or its mathematical in-jokes, but because it captures the specific melancholy of being an adult: the realization that the future isn't what we were promised, but it’s better than facing it alone.

Ultimately, *Futurama* is a warm blanket woven from cold, hard irony. It posits that even a thousand years from now, when we can travel the stars and download celebrities into jars, the things that will matter most are still a good slice of pizza, a loyal dog, and a crew of misfits to help you deliver the package.