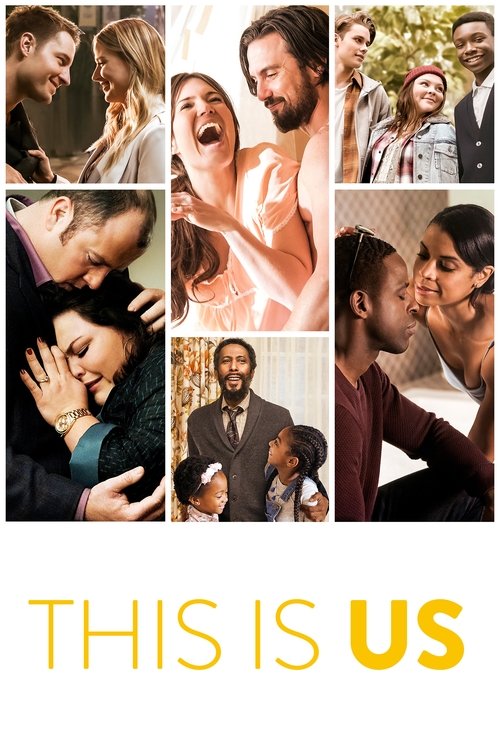

The Architecture of MemoryIn an era of television defined by cynical anti-heroes and dystopian anxieties, *This Is Us* arrived in 2016 as a radical counter-argument: a show that dared to be earnestly, unashamedly humanist. Created by Dan Fogelman, the series is not merely a family drama; it is an intricate study of how time collapses upon itself, where the past is never truly dead, but rather a ghost living in the floorboards of the present. It rejects the linear progression of life, suggesting instead that a family is a single organism stretching across decades, breathing in 1980s Pittsburgh and exhaling in modern-day Philadelphia.

Visually, the series distinguishes itself through a "voyeuristic" intimacy. The camera work, often handheld and reactive, eschews the glossy perfection typical of network television for something that feels lived-in and immediate. Fogelman and his directors utilize a warm, amber-hued palette for the past—not just to evoke nostalgia, but to signal the haze of memory—while the present day is rendered in sharper, cooler tones. This visual dichotomy serves the narrative structure, which is the show’s true protagonist. The editing is not just a transition tool; it is the thematic engine, stitching together a father's smile in 1988 with his son's anxiety attack in 2018, creating a visual rhyme scheme that proves trauma and joy are inherited traits.

The heart of the series lies in the "Big Three"—siblings Kevin, Kate, and Randall—and their parents, Jack (Milo Ventimiglia) and Rebecca (Mandy Moore). While the mystery of Jack’s death initially served as the narrative hook, the show quickly evolved beyond plot twists into a profound exploration of grief's long tail. The performances are uniformly excellent, but Sterling K. Brown’s portrayal of Randall, a Black child adopted into a white family, offers the show’s most complex emotional terrain. His struggle is not just one of identity, but of a desperate need to control a chaotic universe—a direct response to the foundational trauma of his upbringing.

One cannot discuss *This Is Us* without addressing its sentimental weaponization. It is a machine designed to extract tears, yet to dismiss it as "manipulative" is to miss the point. The show argues that sentimentality is a valid response to the human condition. A key scene involving Kevin explaining his painting to his nieces—describing life as a canvas where "everyone is in the painting, everywhere, all the time"—perfectly encapsulates the show’s philosophy. It suggests that death is not an exit, but a change in the color palette. This is most evident in the infamous "Super Bowl Sunday" episode, where the mundane horror of a faulty slow cooker becomes a generational demarcation line, forever splitting the family's timeline into "before" and "after."

Ultimately, *This Is Us* stands as a monument to the idea that we are all collages of the people who raised us and the people we lost. It navigates the treacherous waters of melodrama with a sincerity that is disarming. In a cultural landscape often obsessed with deconstruction and irony, this series offered a six-season embrace, reminding us that while we cannot change the tragic chapters of our history, we can choose how to read them. It is a flawed, sometimes overwrought, but deeply necessary piece of art that affirms the weight of ordinary lives.