✦ AI-generated review

The Dust on the Hem

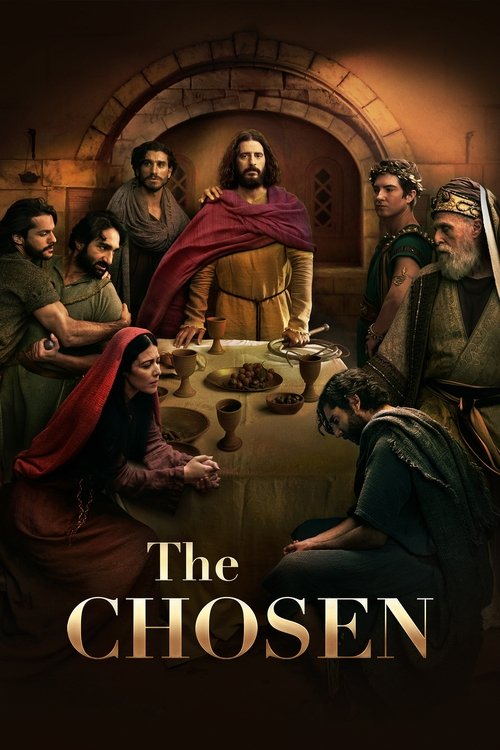

For nearly a century, cinema has struggled to solve the "Jesus problem." In the hands of Hollywood, the Nazarene usually appears as a stoic, British-accented figure gliding three inches above the ground, speaking in reverb-heavy King James English. He is rarely a man; he is a stained-glass window waiting to be installed. Dallas Jenkins’ *The Chosen*—a crowdfunded anomaly that bypassed the traditional studio system to become a global phenomenon—succeeds precisely because it smashes that window. It is a work of "sanctified imagination," a series that dares to ask what the disciples ate for breakfast and whether the Messiah ever cracked a joke.

To view *The Chosen* merely as a religious tool is to miss its significance as a piece of television. Jenkins frames the narrative not through the omniscience of the protagonist, but through the chaotic, messy lives of those in his orbit. The series acts as a backstage pass to the Gospels. We do not begin with the halo; we begin with the debt, the marital strife, and the political oppression of first-century Judea. The visual language reinforces this grounded approach. The camera is often handheld and intimate, lingering on the dirt under fingernails and the sweat on brows. It eschews the polished, golden-hour glow of typical faith-based productions in favor of a textured, dusty realism that makes the miracles feel physically earned rather than digitally inserted.

At the center of this deconstruction is Jonathan Roumie’s portrayal of Jesus, which is arguably the most radical reinterpretation of the figure in modern media. Roumie plays him not as a remote deity, but as a man comfortable in his own skin—warm, tactile, and startlingly humorous. There is a scene early in the series where Jesus is seen alone, practicing a sermon, struggling to find the right words. It is a moment of profound vulnerability that humanizes the divine in a way few theologians would dare. When he winks at a disciple or dances at a wedding, he bridges the gap between the sacred and the mundane, suggesting that holiness is not the absence of humanity, but the perfection of it.

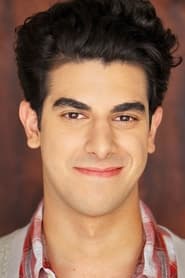

The show’s boldest stroke, however, is its ensemble work. The disciples are not the bearded monoliths of Renaissance art; they are a bickering, fractured family. The decision to portray Matthew (Paras Patel) as neurodivergent—obsessive, socially awkward, and gifted with numbers—is a masterstroke of modern adaptation. It reframes the "tax collector" archetype from a villain into an outcast who finds logic and safety in the Messiah’s teachings. By giving the disciples distinctive psychologies and modern anxieties, Jenkins allows the audience to see themselves in the text. We understand why Peter is impulsive; we feel Mary Magdalene’s trauma.

As the series has progressed through its four released seasons, the narrative weight has shifted from the joy of the initial "come and see" to the looming shadow of Jerusalem. The writing occasionally stumbles into anachronism, and the pacing can suffer from the bloat typical of streaming-era television, yet the emotional core remains devastatingly effective.

*The Chosen* is not just a retelling; it is a reclamation. It rescues the greatest story ever told from the stiff grip of iconography and returns it to the realm of flesh and blood. It posits that the most miraculous thing about this history was not just the walking on water, but the willingness to walk through the dust with people who were utterly, beautifully broken.