✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Desperation

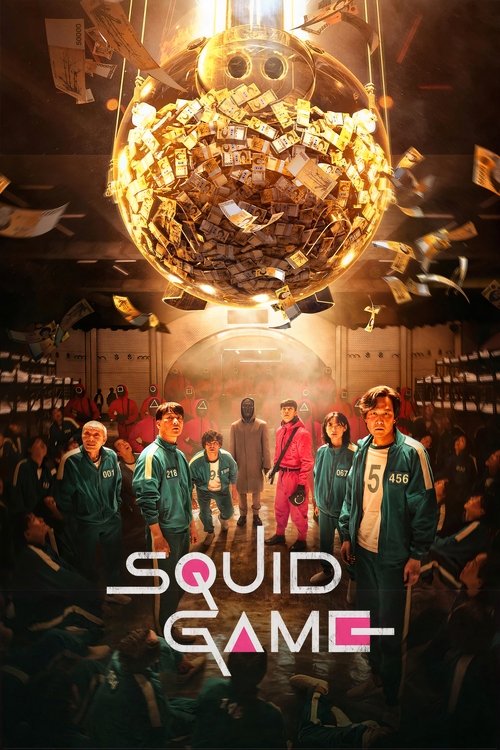

It is a profound irony of the modern streaming era that *Squid Game* (2021), a searing indictment of capitalist exploitation and the commodification of human life, became one of the most consumed digital commodities in history. To view Hwang Dong-hyuk’s survival drama merely as a thrill ride is to miss its terrifyingly sober heart. This is not simply a show about people playing games for money; it is a fable about the "Hell Joseon"—a contemporary South Korean term for a socio-economic reality so stifling that hell seems like a lateral move—that metastasized into a universal anxiety. We did not just watch *Squid Game*; we recognized the panic in its eyes.

Visually, the series is a masterclass in cognitive dissonance. Hwang constructs a world that looks like a confectionary nightmare—a Wes Anderson film stripped of its whimsy and drenched in blood. The set design is deliberately infantile: oversized playgrounds, pastel staircases inspired by M.C. Escher, and the bright, primary colors of early childhood. This aesthetic choice is not merely stylistic; it is thematic warfare. By framing brutal executions within the visual language of nostalgia, the series suggests that the cruelty of the adult economic world is an extension of the playground’s Darwinian rules. The recurring motif of the faceless pink-suited guards reduces the oppressors to shapes and colors, emphasizing that the system does not need individuals to function—it only needs geometry and obedience.

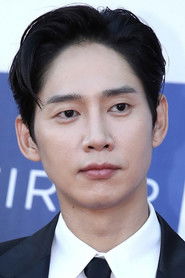

The series is most potent when it abandons the spectacle of the "Red Light, Green Light" massacre for the intimate devastation of the marble game ("Gganbu"). Here, the narrative sheds its action-thriller skin to reveal a tragic stage play. Forced to pair off with their closest allies, the players are stripped of the illusion that they can survive together. The betrayal is intimate, quiet, and heartbreaking. The focus shifts from the physical threat of a bullet to the moral threat of what one must become to survive. We watch Seong Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), our flawed and deeply human protagonist, manipulate a devastatingly vulnerable old man to save his own skin. It is a scene of excruciating tension that indicts the audience as much as the character: in a zero-sum game, decency is the first luxury to be discarded.

The performances anchor this high-concept allegory in sweating, trembling reality. Lee Jung-jae does not play a stoic action hero; he plays a desperate, pathetic, and occasionally unlikable father who has been ground down by bad luck and worse choices. His survival is rarely a matter of skill, but of desperate, clawing luck. This subverts the typical survival genre trope where the "best" man wins. In *Squid Game*, the winner is simply the one left standing after the moral slaughter.

Ultimately, *Squid Game* transcends its genre trappings because it refuses to offer the catharsis of a revolution. The players return to the game voluntarily, a narrative decision that transforms the series from a hostage thriller into a grim existential meditation. They choose the possibility of death over the certainty of financial ruin, a choice that serves as the show’s darkest verdict on modern society. The horror is not the sniper in the tower; the horror is that for 456 people, the sniper offers better odds than the world outside.