✦ AI-generated review

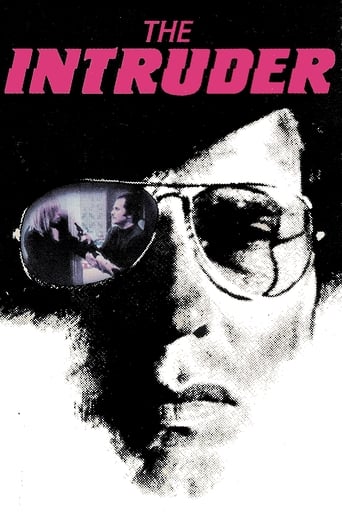

The Education of a Survivor

The "protective father, endangered daughter" narrative has become modern cinema’s favorite muscular lullaby. From *Logan* to *The Last of Us*, we have grown comfortable with the rhythm of the gruff, violent patriarch shepherding innocence through a fallen world. But Nick Rowland’s *She Rides Shotgun* (2025) disrupts this comfort. It does not treat violence as a cool necessity of the road; it treats it as a contagion. In Rowland’s hands, the road trip isn't about saving a child’s life, but witnessing the slow, heartbreaking death of her childhood.

Adapted from Jordan Harper’s novel, the film operates in the dusty, sun-bleached neo-noir tradition of the American Southwest. Rowland, whose previous work *Calm with Horses* demonstrated a talent for finding tenderness in brutal men, applies a similar tactile grace here. Visually, the film is claustrophobic despite the open highways. The camera, often handheld and hovering at the eye level of 11-year-old Polly (a revelatory Ana Sophia Heger), traps us in her confusion. We are not omniscient observers; we are passengers in the backseat, limited to what a terrified child can see and understand.

This commitment to perspective is the film’s strongest stylistic weapon. In one of the most discussed sequences, adults argue about life-and-death logistics in a cluttered living room. Yet, the camera drifts away from their faces to focus intensely on a tank of hermit crabs. It is a brilliant stroke of directorial empathy—mimicking the way a child’s mind dissociates from trauma by fixating on the mundane. The violence, when it erupts, often feels louder and more jarring because we have been lulled into Polly’s small, quiet world.

At the center of this storm is Taron Egerton as Nate, a performance that essentially sandblasts the charisma of *Kingsman* off his bones. Egerton is physically transformed—tatted, sweaty, and vibrating with the desperate energy of a prey animal—but he resists the urge to play the "cool" anti-hero. Nate is not a super-soldier; he is a screw-up trying to do one thing right. The chemistry between him and Heger is not built on witty banter but on a shared, suffocating silence. The film’s emotional anchor is a scene in a dingy motel bathroom where Nate cuts and dyes Polly’s hair to disguise her. It is a moment of profound intimacy and care, yet the context—stripping away her identity to survive his mistakes—renders it tragic.

If the film stumbles, it is because the "Girl Dad" genre has such rigid structural bones that the third act feels inevitable rather than organic. The machinations of the Aryan brotherhood gang and the corrupt police force occasionally veer into B-movie melodrama that threatens to cheapen the human story.

However, *She Rides Shotgun* recovers in its final moments. It refuses the catharsis of a happy ending where the family is made whole. Instead, it offers something colder and more honest. By the time the credits roll, we realize that Nate hasn’t just taught Polly how to survive; he has inadvertently enrolled her in his own violent worldview. The tragedy isn’t that she might die, but that to live, she has to become just like him. It is a tense, sweating piece of cinema that suggests the worst inheritance a father can leave isn't debt, but instinct.