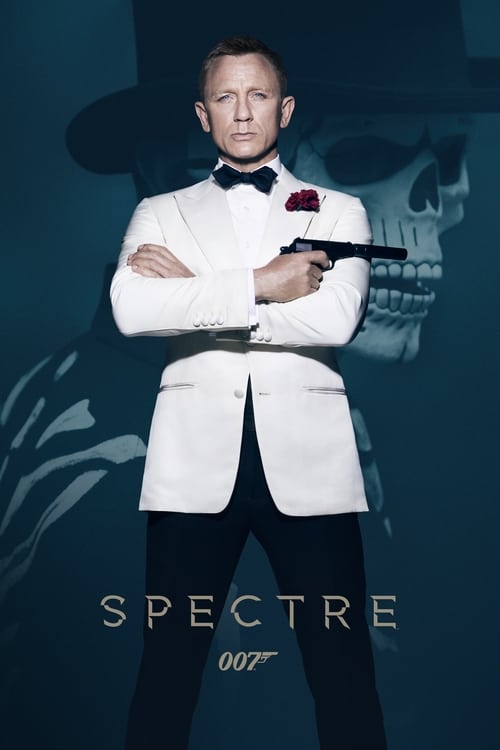

The Ghost in the MachineIf *Skyfall* was a meditation on the relevance of the old guard in a digital world, *Spectre* is a desperate attempt to prove that the old guard can still play by the new rules. Sam Mendes returns to the director’s chair with a burden that would crush a lesser filmmaker: following up the most financially successful and critically acclaimed Bond film in history. The result is a movie that feels like a lavish, beautiful, and occasionally hollow mausoleum—a monument to a cinematic legacy that is struggling to decide if it wants to be a gritty psychological drama or a campy Saturday morning serial.

The film opens with a sequence that is arguably the technical peak of Daniel Craig’s tenure. We are dropped into the clamor of the Day of the Dead festival in Mexico City. Mendes and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema orchestrate a dizzying, continuous tracking shot that follows Bond through the macabre pageantry of skeletons and floats.

It is a breathtaking piece of cinema—immersive, tactile, and dripping with atmosphere. The camera glides with the confidence of a predator, promising a film of operatic grandeur. However, this opening also establishes the film’s central problem: it is a ghost story where the ghosts are not just characters from Bond’s past, but scenes from previous movies. The helicopter fight, the train brawl, the mountaintop clinic—they all feel like echoes of better sequences from *From Russia with Love* or *On Her Majesty's Secret Service*, reassembled with a bigger budget but less soul.

Visually, the film is a departure from Roger Deakins’ vibrant, digital sharpness in *Skyfall*. Van Hoytema shoots on 35mm film, bathing the screen in golden, dusty hues and deep, velvety shadows. The meeting scene in Rome, where Bond infiltrates the secret criminal organization, is a masterclass in lighting. We see a gathered cabal of criminals in a palatial hall, stripped of the usual sci-fi gadgetry, reduced to whispers in the dark.

Here, Mendes tries to reintroduce the element of myth. Christoph Waltz, as the architect of Bond’s pain, plays the role with a detached, impish irony that initially works. But the script commits a cardinal sin of modern franchise filmmaking: it over-explains. By attempting to retroactively tie the villains of *Casino Royale*, *Quantum of Solace*, and *Skyfall* into a single corporate flowchart headed by Waltz, the film shrinks the world rather than expanding it. The revelation of a fraternal connection between hero and villain—a soap opera twist—robs their conflict of its ideological weight. Bond fights not against a terrifying worldview, but against a jealous sibling with a drill.

The emotional core of the film rests on Léa Seydoux’s Madeleine Swann, a character tasked with thawing Bond’s heart after the tragedy of Vesper Lynd. Seydoux is a formidable actress, bringing a prickly intelligence to the role, but the romance feels mandated rather than earned. We are told they are in love, but we rarely *feel* the heat that would justify Bond walking away from the service.

Ultimately, *Spectre* collapses under its own ambition to be the "Ultimate Bond Movie." It tries to reconcile the brutal, grounded realism of the Craig era with the fantastical escapism of the Connery and Moore years. It wants to have its martini and spill it too. While it offers moments of undeniable beauty and a performance from Craig that remains physically committed, it feels like a film looking backward, trapped in the very past it claims to have outrun. It is a spectacle, certainly, but one that leaves you longing for the silence that follows the noise.