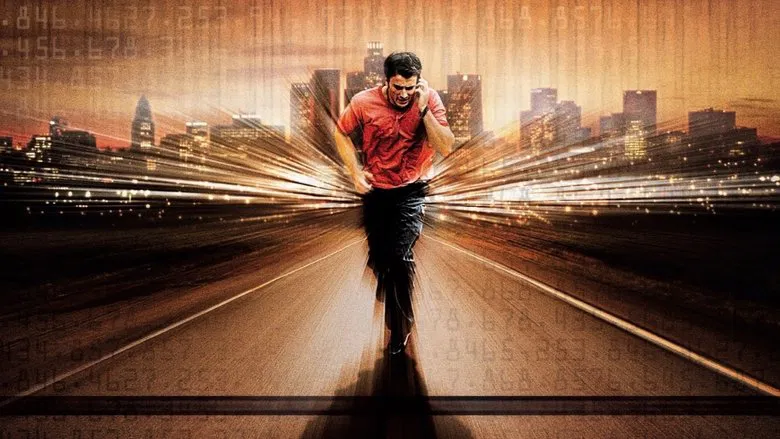

The Infinite LineThere is a specific, now-vanished anxiety that belongs to the early 2000s: the fear of the dropping bar, the fading signal, the dying battery. Before the smartphone became a portal to the entire internet, it was simply a lifeline—a fragile silver thread connecting two voices across a city. David R. Ellis’s *Cellular* (2004) operates within this specific technological window, turning a Nokia handset into an instrument of Greek tragedy. Written by Larry Cohen, the B-movie auteur who also penned the claustrophobic *Phone Booth* (2002), this film serves as that picture’s kinetic inverse. Where *Phone Booth* was paralyzed by stasis, *Cellular* is defined by velocity, suggesting that in the modern sprawl of Los Angeles, connection is the only thing keeping us from disappearing entirely.

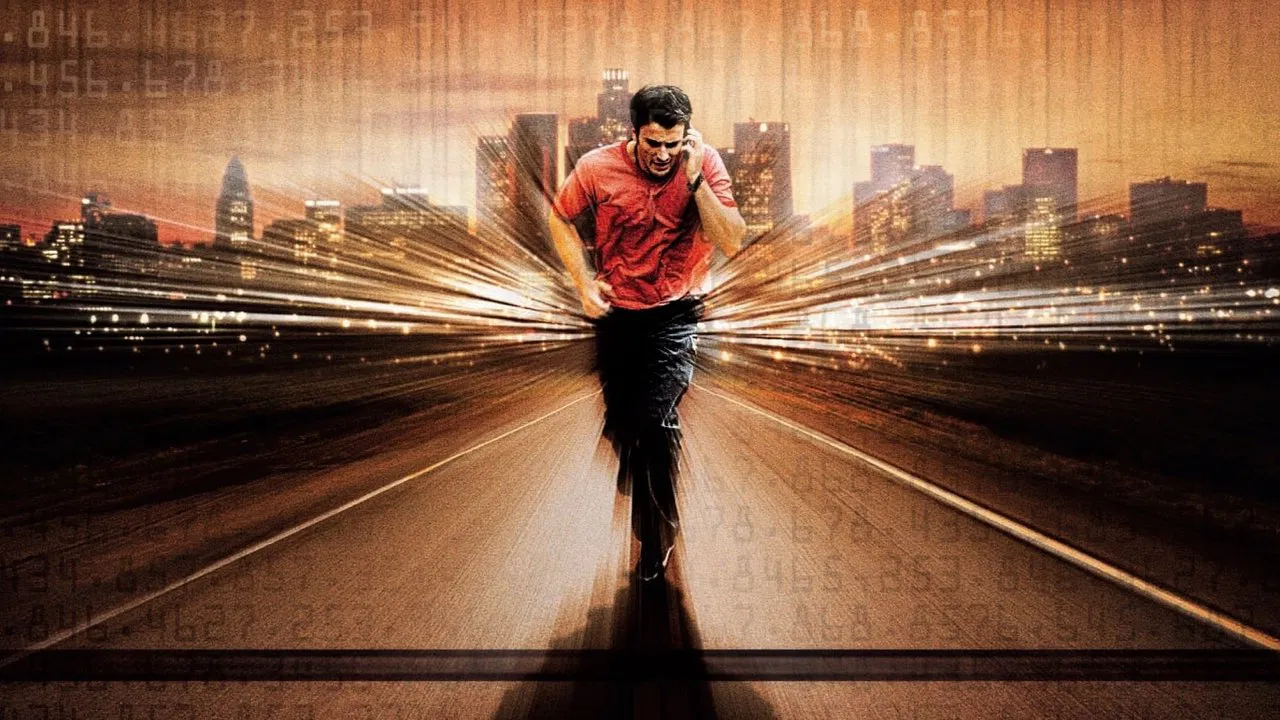

Ellis, a director whose background in stunt coordination (later seen in the gleeful carnage of *Final Destination 2*) informs every frame, treats the camera not as an observer but as a participant in the chase. The visual language of the film is sun-bleached and frantic, capturing the unique, hazy lighting of L.A. traffic jams. The city is presented not as a glamorous backdrop, but as a vast, indifferent obstacle course. The film’s tension is derived from the juxtaposition of two distinct worlds: the claustrophobic, dusty attic where Jessica Martin (Kim Basinger) is imprisoned, and the bright, open-air chaos of the Santa Monica pier where Ryan (Chris Evans) answers her random, desperate call.

The film’s emotional weight rests almost entirely on the shoulders of Kim Basinger. It would have been easy to play Jessica as a generic damsel, but Basinger imbues her with a raw, trembling panic that elevates the material above its pulp origins. When she hotwires the smashed rotary phone to dial a random number, her desperation is palpable. She isn't just fighting for survival; she is fighting to be heard. On the other end of the line is a pre-Captain America Chris Evans, playing a carefree slacker. His performance is crucial precisely because he is not an action hero; he is an audience surrogate, terrified and out of breath, driven by the moral imperative that one simply cannot hang up on a screaming stranger.

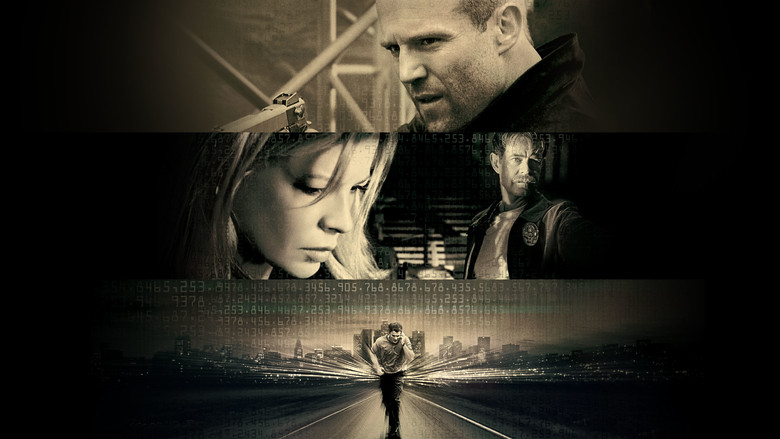

The antagonist, played with icy efficiency by Jason Statham, represents the brutality of the disconnected world. He is a shark in a leather jacket, moving through the city with a purpose that contrasts with Ryan’s stumbling heroism. But the true villain of the piece is the technology itself—or rather, its limitations. The screenplay cleverly weaponizes the everyday frustrations of 2004 mobile technology: signal dead zones, the "low battery" chirp, and the chaotic absurdity of cross-connections. These are not just plot devices; they are metaphors for the fragility of human relationships. The phone is a lifeline, but it is also a leash, dragging Ryan through car chases and gunfights, demanding that he care about a woman he has never met.

In the landscape of modern cinema, where stakes are often cosmic and heroes are invincible, *Cellular* feels refreshingly human. It posits that heroism is not about strength or training, but about the willingness to listen. It is a high-octane thriller, yes, but at its heart, it is a story about the profound intimacy of a voice in your ear, whispering that they need you, and the terrified realization that you are the only one who can help.