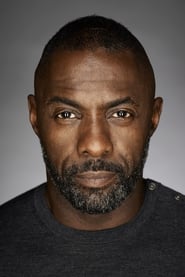

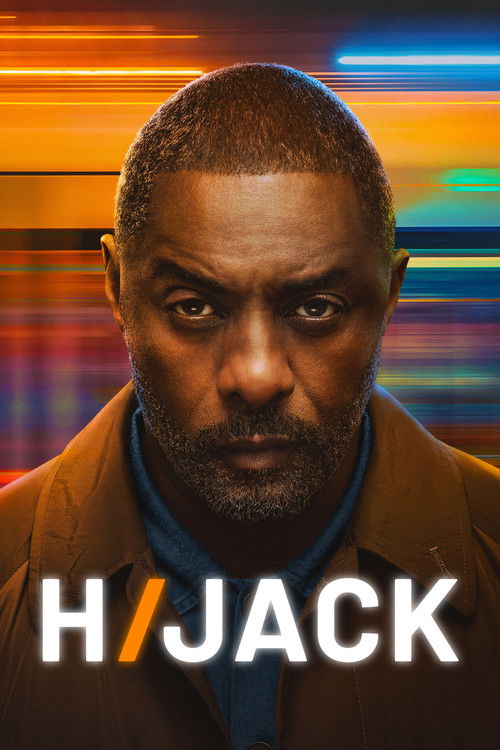

The Art of the Deal at 30,000 FeetThe "real-time" thriller is a dangerous narrative gamble. It invites the audience to scrutinize every second, stripping away the convenient ellipses of editing that usually hide plot holes. When *24* popularized the format, it relied on the adrenaline of Jack Bauer sprinting through Los Angeles. *Hijack*, the 2023 limited series from creators George Kay and Jim Field Smith, attempts a similar temporal trick but swaps the gun for a different weapon: the velvet tongue of a corporate negotiator. By placing Idris Elba in a seat rather than a saddle, the series offers a fascinating, if occasionally turbulent, study of soft power in a hard vacuum.

The premise is elegantly simple: a seven-hour flight from Dubai to London, unfolded over seven hour-long episodes. But the show’s distinct texture comes from its refusal to turn Sam Nelson (Elba) into an action hero. Nelson is a "closer" for big business mergers, a man whose superpower is reading the room—even when that room is a claustrophobic metal tube held hostage by armed assailants. The directors utilize the geography of the plane brilliantly, turning the curtains between First Class and Economy into rigid borders of caste and information. The cinematography emphasizes the stifling proximity of air travel; we feel the stale air and the terrifying intimacy of being seated inches away from one's potential executioner.

However, the series bifurcates its tension. While the airborne drama is a masterclass in micro-expressions and whispered strategy, the terrestrial subplot—involving British government bureaucracy and a shadowy stock market conspiracy—often feels like a different, lesser show. The transition from the sweaty, immediate terror of Flight KA29 to the sterile conference rooms of London drains the momentum. The ground game is necessary for the plot mechanics (the "why" of the hijacking), but it lacks the visceral "how" that Elba commands in the sky.

At the heart of the series is a subversion of the hijacker archetype. Led by Stuart (a terrifyingly brittle Neil Maskell), the antagonists are not ideologues but desperate gig workers in a criminal enterprise. This allows Nelson to engage them not as monsters, but as disgruntled employees in a deal gone wrong. There is a profound humanism in how Nelson operates; he doesn't want to defeat the bad guys so much as he wants to manage them. He manipulates the social contract of the airplane, using the passengers' collective anxiety and the hijackers' lack of a contingency plan to engineer a fragile equilibrium. It is a performance of restraint, where a raised eyebrow conveys more panic than a scream.

Yet, the narrative strains under its own high-concept weight in the final stretch. As the motivations shift from survival to financial market manipulation, the show loses some of its primal fear. The revelation of the specific mechanics behind the hijacking feels somewhat anticlimactic, a spreadsheet solution to a life-or-death problem. The finale, while gripping, relies on a cascade of coincidences that test the viewer's suspension of disbelief, particularly regarding who exactly ends up piloting the plane.

Ultimately, *Hijack* succeeds not because of its procedural logic, which frays upon inspection, but because of its psychological acute awareness. It captures the modern anxiety of helplessness—the feeling of being strapped in, devoid of control, trusting that someone, somewhere, knows how to land the machine. It posits that in a world of chaotic violence, the most valuable skill isn't the ability to fight, but the ability to talk. It is a throwback to the intelligent, mid-budget thrillers of the 90s, polished with a modern sheen, reminding us that sometimes the most thrilling action is a man simply thinking his way out of a corner.