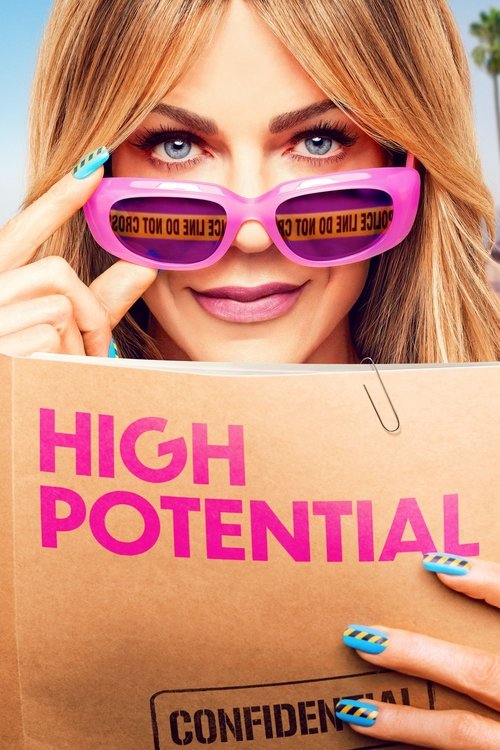

The Chaos of CompetenceFor nearly a decade, the "Blue Sky" era of television—that distinct period of sun-drenched, character-driven procedurals like *Psych* and *Monk*—seemed all but extinct, replaced by the desaturated grimness of prestige crime dramas where every detective fights a losing battle against their own nihilism. *High Potential* (2024), adapted by Drew Goddard from the French smash hit *HPI (Haut Potentiel Intellectuel)*, arrives not just as a revival of that brighter aesthetic, but as a fascinating interrogation of who we allow to be a genius in America.

It is telling that Morgan Gillory (Kaitlin Olson) enters the frame not as a brooding savant in a bespoke suit, but as an invisible laborer dancing to The Roots while knocking over files in a police precinct. She is the cleaning lady, a ghost in the machine of law enforcement, until she rearranges an evidence board with the casual annoyance of someone straightening a crooked painting.

The series is visually literate in a way network procedurals rarely bother to be. Where BBC’s *Sherlock* visualized genius through floating text and cold, calculated geometry, *High Potential* renders Morgan’s intellect as a chaotic, colorful assault of information. The direction embraces a "pop" sensibility; when Morgan deduces a suspect's location from a receipt and a candy wrapper, the camera snaps and zooms with a frenetic energy that mirrors her unquiet mind.

This visual language serves a specific narrative function: it forces the audience to see the world through the eyes of someone who cannot filter out the noise. The production design contrasts the sterile, grey bureaucracy of the LAPD—inhabited by the stoic, by-the-book Detective Karadec (Daniel Sunjata)—with Morgan’s wardrobe of leopard prints, faux fur, and neon accessories. She is a splash of vibrant disorder in a world of rigid lines.

However, the show’s true engine is not its mystery-of-the-week mechanics, but the casting of Kaitlin Olson. Known for her feral comedic brilliance in *It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia*, Olson here refines that chaotic energy into something deeply human. She plays Morgan not as a superhero, but as a woman exhausted by her own gifts. There is a palpable tragedy in her performance—the idea that having an IQ of 160 is less a superpower and more a social disability when you are a single mother of three trying to pay a mortgage.

The tension between Morgan and Karadec avoids the lazy "will-they-won't-they" trap by rooting their conflict in class and methodology. Karadec represents institutional order; Morgan represents intuitive anarchy. Their friction suggests that the justice system fails not because it lacks data, but because it lacks imagination.

Ultimately, *High Potential* succeeds because it respects the invisible work of survival. It posits that the same skills required to manage a chaotic household on a minimum wage budget—hyper-vigilance, pattern recognition, multitasking—are the same skills required to solve murders. It is a sleek, entertaining piece of television that hides a sharp commentary on class underneath its polished, comedic surface. It suggests that high potential is everywhere, often wearing a janitor's uniform, just waiting for someone to stop looking at the evidence and start looking at the person cleaning it up.