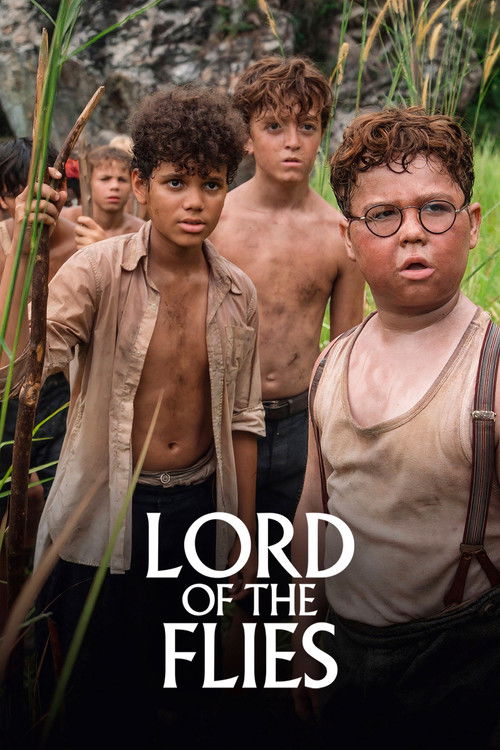

The End of InnocenceIn the vast, terrifying lexicon of British literature, few stories hang as heavy over the collective consciousness as William Golding’s *Lord of the Flies*. It is a text we are often force-fed in classrooms, a parable of original sin we digest before we are old enough to understand the bitter taste. But in this 2026 adaptation, writer Jack Thorne and director Marc Munden have stripped away the academic dust, offering not a mere retelling, but a forensic examination of boyhood in freefall. This four-part miniseries is less an adventure story and more a psychological horror, suggesting that the true island isn't the one surrounded by water, but the isolated, terrifying geography of the developing male mind.

Munden, whose visual signature is often defined by a kind of sickly, hyper-saturated beauty, transforms the tropical setting into a hallucination. The island is not a paradise lost; it is a purgatory found. The camera lingers on the sweating, sun-blistered skin of the cast with an intensity that feels almost intrusive. We are not watching actors; we are watching biology decay. The sound design, bolstered by a haunting score from Hans Zimmer and Kara Talve, eschews the typical orchestral swells for something more primal—insects buzzing like static, the ocean roaring like a threat. It creates a sensory experience that is suffocatingly real, trapping the viewer in the humidity alongside the stranded choirboys.

The structural choice to dedicate each of the four episodes to a specific perspective—Piggy, Jack, Simon, and Ralph—is the series’ most potent innovation. It allows Thorne to inject a modern interiority into archetypes we thought we knew. Lox Pratt’s Jack is not merely a villain-in-waiting but a boy hollowed out by a lack of love, his aggression a desperate armor against his own fragility. Winston Sawyers gives Ralph a burden of leadership that feels crushing, a "dull democrat" paralyzed by the impossibility of consensus. But it is David McKenna as Piggy who shatters the heart. McKenna plays him not as a caricature of intellect, but as a child acutely aware of his own doom. When he clutches the conch, it isn't just a symbol of order; it is a desperate plea for a world that makes sense, a world that has already abandoned them.

What makes this adaptation sear, however, is its refusal to look away from the "conversation" about toxic masculinity that has dominated the last decade of cultural discourse. Thorne’s script (echoing themes from his previous work *Adolescence*) suggests that the violence on the island is not a regression to animal instinct, but a learned behavior—a tragic pantomime of the adult world they have left behind. The face paint and the sharpened sticks are not just tools of survival; they are costumes of power worn by children who have seen too much. The tragedy isn't that they become savages; it's that they become men, in the worst possible sense of the word.

Ultimately, this *Lord of the Flies* is a difficult, demanding watch. It lacks the sanitized distance of a school play or the abbreviated punch of a 90-minute film. It asks us to sit in the discomfort of moral collapse for four hours. By the time the credits roll on the final devastating frame, we are left with a silence that is deafening. We realize that the beast was never in the jungle. It was in the systems we built, the boys we raised, and the mirror we are too afraid to look into. This is essential, harrowing television that proves some stories don't just age; they metastasize.